Rehabilitation and Reintegration Path of Kosovar Minors and Women Repatriated from Syria

Introduction and Context

Following the end of the 1998-99 armed conflict, Kosovo entered a complex sociopolitical transition as it struggled to recover and rebuild its war-torn economy. Against this backdrop of profound challenges and rapid transformative changes this nascent country experienced a sharp rise in radicalization into violent extremism.1 The start of the Syrian civil war in 2011 marked the beginning of an unprecedented wave of Kosovar nationals traveling to the Middle East—including with family members—to join armed militias and designated terrorist groups fighting against the Syrian government, or to migrate to territories administered by them.2

As of August 2020, the majority of the Kosovar foreign fighters and family members had returned home, often accompanied by children born in the conflict theater. In April 2019, Kosovo became one of the first among few countries to have voluntarily and publicly repatriated a large group of nationals from Syria, mostly non-combatant minors and women but also adult male combatants.3 The adoption of this proactive repatriation approach has not been without challenges. At the same time, it has placed Kosovo at the forefront of efforts for the rehabilitation and reintegration of repatriated minors and women from Syria into mainstream society.

This report provides an overview of Kosovar authorities’ initial rehabilitation steps and reintegration efforts. It highlights potential good practices, ongoing challenges, and opportunities for inclusive partnerships with strategic stakeholders. The report also provides recommendations for improved implementation practices, programmatic effectiveness, and increased sustainability.

The report relies primarily on official data and publications by Kosovar authorities, international organizations, and think tanks on the rehabilitation and reintegration of minors and women repatriated from Syria and Iraq. It also reflects the views, observations and suggestions of civil society practitioners, psychologists, security specialists, researchers, and civil servants—some of whom are directly involved in the rehabilitation and reintegration of repatriated Kosovar nationals— obtained through virtual interviews conducted by the author in August – September 2020 and during in-person and virtual P/CVE working group sessions and policy roundtables organized by international organizations and think tanks in 2020.

Current State of the Issue

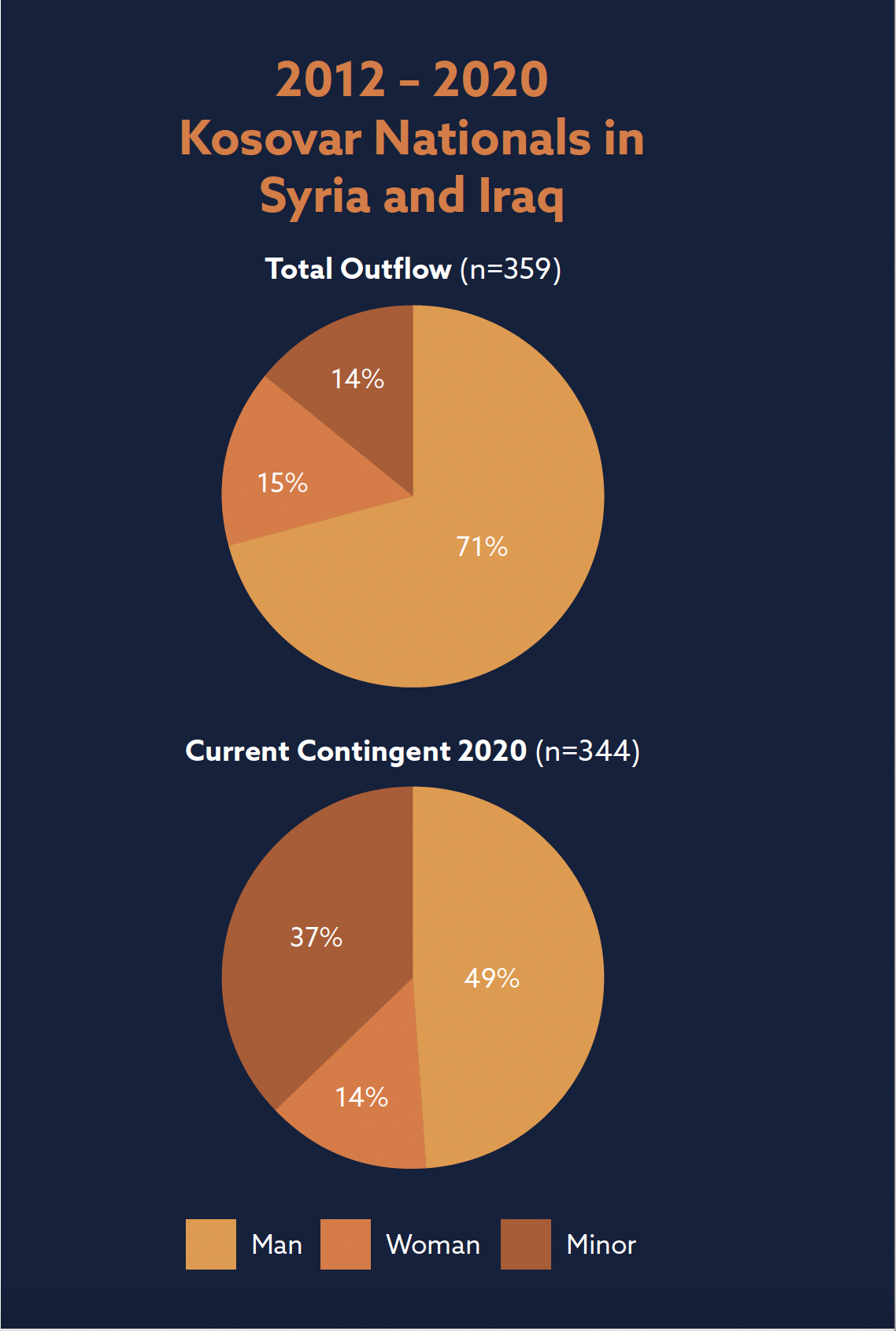

At least 359 Kosovar nationals traveled to Syria and Iraq from 2012 to either join designated terrorist organizations or to migrate to territories controlled or administered by them.4 A previous study found that about 11 percent of Kosovar nationals who traveled to Syria and Iraq during the timeframe in question held dual citizenship and may have departed from other countries.5 About 71 percent of the total contingent were male adults at the time of departure, 15 percent women, and 14 percent minors. At least 81 children were born to Kosovar nationals in Syria and Iraq between 2012 and 2019, bringing the total number of Kosovar nationals (or individuals entitled to Kosovar nationality) to have spent time in Syria and Iraq to 440.

By August 2020, at least 242 Kosovar nationals had returned to Kosovo, including 110 individuals repatriated in April 2019 by the Kosovar government with assistance from the U.S. military. The number of Kosovar nationals remaining in Syria and Iraq is estimated to be 102, of whom 47 are adult male, 9 women, and 46 minors.6 An unspecified number of adult male Kosovars are currently held in Kurdish-controlled prisons, while the rest continue to be embedded with militant organizations active in Syria.

Of all remaining7 Kosovar nationals who spent time in Syria and Iraq between 2012 and 2020, adult males account for about 49 percent, women 14 percent, and minors 37 percent. This significant demographic shift resulted from an increase of two and a half times in the number of minors due to new births, and a drop of one-third in the number of adult males due to battlefield deaths. In sum, the Kosovar contingent is currently dominated by minors and women, largely considered noncombatants.

Understanding the Paths of Repatriated Children and Women

The highlighted demographic shift from predominantly adult males to mostly minors and women is of particular consequence for policy formulation, resource allocation, and programmatic planning in response to the dynamic needs and risks associated with those repatriated. While much research already exists on male foreign fighters, the place of women and children within the broader strategy of the Islamic State is less explored. Certainly, returning foreign fighters represent a bigger security risk, but the greater numbers of vulnerable children that have returned or will be repatriated demand increased attention. So do their mothers, often the sole caretakers of children whose fathers may have been killed or incarcerated. The first step to understanding the implications of this demographic shift is unpacking the reasons behind its manifestation and the roles of women and children in the context of the conflict in Syria and Iraq.

The Women

The involvement of women in insurgent movements and terrorist organizations for different motivations and in a broad range of roles, including as combatants, is well documented. Indeed, stereotypes that depict war and violent extremism as a male domain and women as helpless victims or coerced wives who lack agency are simplistic and inaccurate. They ignore the fact that just as some women have been coerced or manipulated into joining violent extremist organizations, the participation of others in support roles or active combat has been a direct result of their convictions and uncoerced free will.8

The so-called Islamic State placed strategic importance to attracting and enlisting women to its cause from early on. This approach was particularly driven by its state-forming ambitions in Syria and Iraq that exceeded the seemingly more modest militaristic goals of similar non-state actors in the region. The Islamic State propaganda apparatus portrayed women as key actors in building a utopian Islamist society where they could lead fulfilling lives under Sharia law by supporting and encouraging their jihadi husbands and growing the next generation of fighters. As a result, an unprecedented number of women—in many cases accompanied by their children—traveled to territories controlled by the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq.9 This migratory wave of women supporters gained particular momentum in the immediate aftermath of the proclamation of the so-called Caliphate in June 2014. In the case of Kosovo, about 80 percent of the women known to have traveled to Syria did so between the second half of 2014 and 2015.

Unlike other similar organizations like al-Qaeda and the Taliban, the Islamic State has allowed women recruits a prominent operational role on social media platforms.10 Accordingly, these women have actively engaged in the dissemination of propaganda, recruitment of other women, and fundraising on behalf of the Islamic State.11 They have also carried out functional roles as teachers, nurses, doctors, etc, which are much required in strictly gender segregated societies. Although the documented cases of women’s participation in armed combat in Syria and Iraq are few, the Islamic State managed to militarize women by reviving the model of the early mujahidat.12

Women are also known to have been enlisted in policing roles by the Islamic State as part of the all-female al-Khansaa brigade, a religious enforcement unit prone to the use of violence.13

In sum, women who migrated to territories controlled by the Islamic State have played a wide range of integral roles for the implementation of their organization’s vision and strategy, such that has no precedent in previous waves of foreign fighter migrations. Some of them continue to embrace these roles with fervor and determination despite the territorial defeat of the Islamic State.14 A woman who had managed to smuggle herself out of Syria told a journalist: “We will bring up strong sons and daughters and tell them about the life in the caliphate; Even if we hadn’t been able to keep it, our children will one day get it back.”15

The Children

As in the case of women, children have been an integral part of the Islamic State’s strategic vision and efforts to secure the longevity of the organization. Historically, minors have been enlisted in various roles, including as child soldiers, by both state and non-state military organizations.16 Yet, due to its unparalleled success in recruiting foreign adults, the Islamic State succeeded in attracting record high numbers of foreign minors, exceeding previous efforts by other jihadi organizations.

The numbers of children increased as women were encouraged “to have as many children as their bodies would permit and be open to remarriage if their husband was killed on the battlefield.”17 A study from 2018 found that at least 4,640 foreign minors were living at some point in the territories controlled by the organization.18 The territorial defeat of Islamic State at Baghouz in March 2019 revealed that the number of children affiliated with foreign fighters was much higher. Over 7,000 foreign minors were evacuated by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and sheltered at Al-Hol, a camp for Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) in north Syria.19

Numerous publications and propaganda material released by Islamic State media affiliates testify to its extensive exploitation of children. Widely disseminated videos show young boys, dubbed “the Cubs of the Caliphate,” socializing, playing, and receiving schooling, but also attending camps for religious indoctrination and military training, and in some cases even engaging directly in acts of choreographed violence.20 In the Caliphate, children were routinely exposed to stonings and executions with the intention of desensitizing them to violence or death as a way of preparing them for the battlefield.21

The extent of psychological trauma caused to these children from prolonged exposure to violence, destruction, abuse, bombings, and loss of relatives is yet to be understood. Likewise, the implications of such traumatic experiences to their long-term physical and psychological wellbeing are unclear. Without a thorough analysis of the scarring experiences these children have gone through, as well as the political strategy and dynamics that set these experiences in motion, it will be hard to fully understand or reverse the effects of indoctrination and trauma they have endured or the risks associated with them. In fact, as some scholars argue, uninformed or rushed responses in such cases may have counterproductive effects.22

In sum, despite its territorial defeat in Baghouz in early 2019, the Islamic State’s strategic vision and ideology continue to enjoy support, including among those stranded indefinitely in IDP camps in northern Syria. Both women and children have appeared in footage shot inside Al-Hol, chanting Islamic State slogans, waving its flag, and issuing statements reconfirming alliance to the organization.23 By repatriating its women and children from Al-Hol shortly after their evacuation from Baghouz, Kosovo removed them from an environment that in the past year has become synonymous with abandonment, extremism, and detention without recourse to justice, all of which are factors that increase the risk of further radicalization and trauma, especially among minors.

The Rehabilitation and Reintegration Experience

Kosovo’s proactive repatriation of children, women, and a limited number of male combatants from Syria is in line with what various national security experts and scholars propose as the most viable approach from a legal, moral, and long-term security perspective.24, 25 Many constitutions and national laws, as well as international conventions and U.N. Security Council Resolutions, bind countries to protect their citizens’ rights, ensure the children’s well-being, investigate war crimes committed by their nationals, and bring terrorists to justice.26 Despite this, most countries are reluctant to repatriate.

Furthermore, there is growing consensus among experts that coordinated repatriation of foreign fighters and family members, along the lines of Kosovo’s approach, allows for a more effective administration of justice. As an example, as of August 2020, three repatriated men and 27 repatriated women had been found guilty and sentenced for terrorism offences by Kosovar courts. Judging from the above, despite not being a member of the U.N. or a signatory to international laws and conventions, Kosovo appears to have taken multiple responsible steps, well aligned with them. It has done so not only by taking responsibility for its citizens, but also by administering justice without delay, thus opening a possible path to the returnees’ rehabilitation and reintegration into mainstream society. Moreover, the act of repatriation in itself is arguably one of the most effective counter messages to the hateful narratives of the Islamic State.

Initial efforts and encouraging steps

Strategic and institutional frameworks

The de-radicalization and reintegration of radicalized persons is one of four strategic objectives of the Strategy on Prevention of Violent Extremism and Radicalization (2015-2020) drafted by the Kosovo government in 2015.27 While the document does not discuss “rehabilitation” as a separate process, or provide definitions of “deradicalization” and “reintegration,” the inclusion of this strategic objective is indicative of the level of importance placed on reintegration. This is broadly described as an inclusive process, implemented in close coordination between relevant line ministries in collaboration with local government authorities, expert practitioners, and representatives of religious communities, with support from international partners and donors. Although the strategy and action plan emphasize the importance of a whole-of-government approach and the critical role of civil society in its implementation, the latter is not included as a key stakeholder within the section dedicated to this strategic objective.

Key implementing institutions for de-radicalization and reintegration efforts include the Ministry of Justice; the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare; the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport; and the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. Listed activities include provision of psychological and religious counselling for inmates, social support for families, and development of new employment programs for reentry. The corresponding action plan for the implementation of the strategy, which is revised annually, includes a list of planned activities under de-radicalization and reintegration efforts. Nevertheless, the document does not identify all financial costs and sources of financing for foreseen activities, which has likely had an adverse impact on their implementation rate.

The National Coordinator for the Prevention of Violent Extremism is another key component of the institutional infrastructure relevant to the rehabilitation and reintegration of returnees. Until recently the coordinator served as the security advisor to the Prime Minister and was in charge of coordinating the implementation of the strategy and action plan. A number of coordinators have held the position for relatively short periods of time since its creation. In July 2020 the functions and responsibilities of the national coordinator were transferred to the Minister of Interior Affairs after the position was extinguished in February 2020 by the previous government.28 The frequent changes in this position have created difficulties in the implementation and coordination of efforts relevant to the rehabilitation and reintegration of returnees.

Another pertinent strategic framework developed in 2017 by the Kosovar government is the National Strategy for Sustainable Reintegration of Repatriated Persons in Kosovo (2018-2022.) Although the document does not include a specific section or dedicated protocols for returning foreign fighters and their families, it has relevant guidelines for the reintegration of persons returning from conflict zones (particularly children and women) and those returning from correctional institutions. According to this document, a key factor affecting sustainable reintegration of repatriated persons is the decentralization of competences and the active participation of local authorities.

In May 2018 the Kosovar government established the Division for Prevention and Reintegration within the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and in October 2018 set up an inter-institutional working group for coordination of efforts, led by the Minister of Justice. The stated mission of this division is to “prevent the radicalization of young individuals and other groups, and to help reintegrate those who have returned from conflict zones.”29 The division has received capacity building assistance from a number of organizations, including the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Nevertheless, insufficient staffing and resources has hindered its effectiveness.30

As of August 2020, an inter-ministerial working group was drafting a revised strategy and action plan for countering terrorist radicalization and recruitment with an enhanced focus on reintegration of returnees from Syria.

Activities following repatriation and a comparative look at alternative approaches

The repatriation of 110 citizens from Syria to Kosovo, including 74 children (nine of them orphans), 32 women, and four men, on 20 April 2019 with the support of the U.S. military, marked the start of a 72-hour emergency plan coordinated by the Division for Prevention and Reintegration. The men were detained at the airport by the police, while the children and women were quarantined at a dedicated reception center where, over the course of three days, they were screened for infectious disease and received medical check-ups, as well as psychiatric and psychosocial evaluations.

Moreover, besides being processed by law enforcement, they were interviewed by social workers in order to identify their immediate needs. In the meantime, families of the repatriated individuals were notified of their arrival and asked about their willingness to receive and accommodate their next of kin after their release from the reception center. Upon completion of the 72-hour emergency protocol, most of the repatriated individuals were released to their families, with the exception of those hospitalized. The completion of the emergency plan was followed by a two-phased approach of rehabilitation and reintegration, discussed separately below.

Processing 106 returnees in three days required a great level of commitment from a small team of medical personnel and first-line practitioners who remained at the reception center throughout the implementation phase of the emergency plan.31 This kind of personal dedication and show of empathy was a particularly encouraging step, especially considering limited resources and the short timeframe. By comparison, for example, the women and children repatriated from Syria to Kazakhstan have been accommodated in dedicated rehabilitation centers for a minimum period of one month, and the psychosocial aspects of their assessment and treatment were only initiated after allowing returnees a period of adjustment. The decision regarding the length of the mandatory accommodation in dedicated centers was taken in order to encourage communication and reflection in an approach corresponding with therapeutic community practices.32 The Kazakh choice to deliver the first stage of rehabilitation efforts to the repatriated women and children through a more structured approach and extended timeframe appears to have yielded some initial good results.33

Also, the fact that all repatriated Kosovar children and women, including nine orphaned children, were released to the care of their welcoming extended families signaled an initial level of acceptance with potentially beneficial effects to their adjustment and reintegration process. Nevertheless, it is unclear from available information whether receiving families were screened for potential symptoms of radicalization. Likewise, it is not clear whether, aside from obtaining the receiving families’ consent to host their blood relatives, the authorities assessed the families’ financial, psychological, or emotional preparedness to accommodate and care for three, four, or more returnees, especially children.

The different approach of French authorities may provide some valuable procedural insights. About 115 French children have returned to France from Syria since 2015, of which 28 were repatriated.34, 35 The latest repatriation operation took place in mid-June 2020 and the children were handed over to judicial authorities and social services. French authorities have prioritized the repatriation of orphans and children whose mothers were willing to surrender custody due to health complications and growing concerns of potential radicalization of their children in the IDP camps.36

As a standard procedure, upon arrival in France, minors appear in front of a juvenile judge and authorities assess the physical and psychological state of health and the viability of returning them to the family of origin. In other words, the judicial authorities evaluate whether or not the relatives and potential caregivers of repatriated minors are radicalized and are able to provide care. So far, the majority of those repatriated have been placed in foster institutions or foster families. Very few have been entrusted to their extended families, and when they are, the families are closely monitored by judicial authorities.37

Initial rehabilitation steps

According to the psychiatrist coordinator for health and mental health under the Kosovar government’s rehabilitation and reintegration program, initial evaluations of repatriated women and children revealed clear signs of PTSD, characterized by sleeplessness, anxiety, depression, panic triggered by loud noises such as airplanes flying overhead or firecrackers, etc. After their release from the reception center, the mental health team provided an option for 24/7 phone consultations to the returnees and their receiving families, especially on how to manage the children’s behavior and adjustment to the new environment.38, 39, 40 The consultations proved helpful in containing the reported tensions that in some cases emerged due to issues of overcrowding and reemergence of past family conflicts.41 The professionalism and generosity shown by the team of 16 psychiatrists and four psychologists providing support and counsel to both returnees and receiving families, sometimes working 15-hour shifts, reportedly helped overcome the stressful transition that nonetheless revealed a critical shortage of personnel.42

During this stage, the Division for Prevention and Reintegration, in coordination with other government agencies, facilitated the returnees’ registration with the civil registry office, issuance of personal identification documents, inclusion in social assistance schemes, and arranged housing accommodation as needed. The municipal family medicine centers have provided vaccination, dental services, and follow-up medical checkups. Cultural and sports activities supported by the International Organization for Migrants were organized in coordination with the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology in order to prepare the transition of children into the formal education system.43 Moreover, the mental health unit reportedly started holding individual sessions with the children and their mothers, integrating other family members at a later stage in a joint session. Children received arts and games therapy to help them deal with trauma, anger, or grief, to release tension, as well as to express and manage their feelings and emotions in non-verbal ways.44

Although there is no reporting on the frequency of individual or group therapy sessions and supporting activities, or the overall achieved progress at the time of writing, comments provided to local media by the coordinator of the health and mental health unit suggest that initial efforts have yielded promising results.45

Initial reintegration steps

Following the preparatory work by the Division for Prevention and Reintegration in coordination with the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 40 children were initially integrated in the education system, including five at the preschool level, 25 at the primary level and 10 in kindergarten. Some issues were reported with access to kindergartens in municipalities that do not have such public facilities. Nevertheless, steps have been taken to subsidize access to private kindergartens as well as public transportation for children attending school.46

With the support of intergovernmental organizations, repatriated women have received parenting training. At least 12 women were enlisted in a sewing course and will be provided with sewing machines and supplies, free of charge, for use after the completion of the course. Other women have been enlisted in a cooking course and will receive cooking supplies upon successful completion of the course. These skills development programs constitute encouraging initial steps that are likely to enhance employment opportunities for repatriated women, including self-employment. Nevertheless, Kosovo’s high unemployment rate and the generally limited professional experience of returnees might complicate their job placement process.

The prospects of future employment, or getting a bank loan for self-employment purposes, were further compromised in the case of some returnees following their convictions on terrorism charges. On 3 September 2019, the Basic Court of Pristina issued the first guilty verdict against a repatriated woman who received two-and-a-half-year suspended prison sentence.47 By August 2020 a total of 27 out of 32 repatriated women were handed down similar suspended prison sentences.

The participation of civil society organizations in rehabilitation and reintegration efforts related to repatriated children and women has so far been limited. The Kosova Rehabilitation Center for Torture Victims is one of the few NGOs that started implementing a project in November 2019. The first goal of the project is to build primary health care providers’ capacities to recognize signs and symptoms of trauma in children. The second goal is to provide psychosocial interventions in the school setting for repatriated children. This later goal has proven harder to pursue, due to lack of direct access to repatriated children and their mothers. In June 2020, Partners Kosovo Center for Conflict Management implemented two trainings with social workers aiming to support the process of reintegration of returned children in the school setting.48 The Kosovo Center for Security Studies started the implementation of a project in November 2019, focusing on the development of interpersonal skills through extracurricular activities aiming to facilitate the process of reintegration for children returnees between the ages 6-13 and other minors that may be vulnerable to radicalization.49

The implementation of these projects, funded by the U.S. Embassy in Pristina, slowed down during March-May 2020 because of social distancing measures imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.50 Moreover, repatriated children during this period were unable to attend online classes regularly because in most cases they did not have access to the electronic devices required to attend classes. The City Hall of Pristina and the NGO Community Development Fund reportedly provided children with the necessary tablet computers to resume class attendance. This is a good example of proactive engagement by local government authorities in addressing the needs of returnees. Nevertheless, despite their potential to substantially expand engagement in the rehabilitation and reintegration process, so far local authorities have mostly provided support with administrative procedures, for example in facilitating issuance of personal identification documentation and school registration.

Ongoing Challenges

Kosovo is currently the country with the highest concentration of returnees from Syria and Iraq— including those repatriated—in Europe, relative to population size. It would suffice to compare Kosovo’s 242 returnees to the European Union’s overall 1,250 returnees to put the size of the problem in perspective.51

At the same time, Kosovo is one of the most modestly resourced countries in Europe, which makes the allocation of adequate financial resources to address the needs and risks associated with the high number of returnees challenging. Also, an over-reliance on foreign donors for P/CVE program funding has made proper planning and successful implementation of activities foreseen in strategic documents less manageable.

Similar to the funding issue, the availability of skilled personnel required to meet the long-term need for the specialized psychosocial support of returnees remains inadequate.52 Interviews with practitioners and reviewed reports revealed a critical shortage of specialized psychologists and social workers, especially in the municipalities hosting most of those repatriated.53

Moreover, the benefits provided under the Kosovo social assistance scheme to repatriated families may not sufficiently address their basic needs. These families, composed of multiple minors and only one caretaking mother, have scant prospects of obtaining additional income from employment in the near future. For example, in one case, a family of six children and one caretaking young mother has to rely on a monthly welfare check of 150 Euro (177 USD). This untenable financial situation is not likely to lead to successful reintegration outcomes.

Closely related to the above, it is important to stress that the repatriated individuals have returned to the same communities where some of them were radicalized before departing for Syria and where, according to recurring counterterrorism (CT) operations, radicalization networks committed to the cause of the Islamic State continue to operate.54, 55, 56 In fact, Kosovo’s high rate of recruitment into violent extremism is, to a large extent, the result of extremist groups’ operations after the war.57 It is therefore conceivable that extremist networks, known to leverage humanitarian aid and social services to promote their extremist agenda, may try to exploit the returnees’ vulnerabilities. The COVID-19 crisis is likely to further expose these vulnerabilities.

Lastly, in Kosovo as elsewhere, polls have revealed concerns among the general population related to returnees from Syria and reservations about accepting them. According to a survey from 2019, about 53 percent of Kosovar respondents were unwilling to accept returning foreign fighters from Syria in their communities, but only 30 percent were unwilling to accept returning women and children.58 In France, by comparison, a survey published in 2019 found that 89 percent of respondents opposed the return of adult fighters, while 67 percent also opposed the return of children from Syria and Iraq.59 It is worth noting the lack of differentiation between men and women in the French poll.

Despite the high rate of general unwillingness to accept returnees in Kosovo, the respondents’ differentiation between foreign fighters and noncombatant children and women returnees is worthy of note. Although the French respondents make a similar differentiation regarding children, their opposition to repatriating them is over twice as high as in Kosovo. Overall, the less adversarial attitude of Kosovar respondents toward the repatriation of children and women is likely conducive to a less challenging process of reintegration. Nevertheless, the concerns of receiving communities must be addressed, since rehabilitation and reintegration efforts and any resulting economic assistance provided to returnees may be misperceived as a reward.60

Opportunities for More Decentralized Efforts and Inclusive Partnerships

The ongoing health and socio-economic crisis resulting from COVID-19 will make it challenging for most countries to allocate adequate resources and attention to CT and P/CVE initiatives.61 Per International Monetary Fund projections, Kosovo’s already frail economy is set to experience a 5 percent contraction in 2020.62 By implication, the economic recession is likely to hamper Kosovo’s P/ CVE efforts. These challenging times nevertheless present opportunities to rethink strategic planning and implementation processes for rehabilitation and reintegration efforts, which have so far been largely centralized and insufficiently inclusive of community-based organizations.

There are a number of reasons why CSOs are strategically positioned to engage in P/ CVE initiatives, including in rehabilitation and reintegration efforts. They are locally based, enjoy unmatched access to communities, and have unique knowledge of relevant dynamics that may help or inhibit reintegration of returnees into mainstream society. Moreover, they have legitimacy due to their independence from the government, have experience in working with marginalized sections of the society, and have a genuine interest in directly promoting their community’s wellbeing and safety.63

By virtue of all the above, they are well positioned to work with returnees and their families, engage with receiving communities, and coordinate efforts with local government stakeholders. There are numerous examples of CSOs engaged in rehabilitation and reintegration efforts in a range of roles by providing psychosocial and trauma counseling, enhancing vocational and trade skills, delivering academic training, etc.64 It must be pointed out that while community-based organizations may not have a sufficient level of expertise or staff to deal with all aspects of rehabilitation and reintegration, their valuable input may help mitigate the shortage of resources at the disposal of central or local government authorities.

According to interviews with first line practitioners and reviewed reports, the participation of local government authorities in drafting the P/CVE strategy and implementing activities foreseen in its action plan has been insufficient.65 This has been a missed opportunity that can and should be rectified. From a practical standpoint, it is not sustainable in the mid-to-long run to have the core rehabilitation and reintegration efforts developed, coordinated, and implemented by staff operating from the capital city when the repatriated individuals have been distributed across nine or more Kosovar municipalities. While the local authorities’ support with administrative procedures related to repatriated individuals has been a valuable addition during the initial stages, they have the potential to take on a range of additional roles.

The central government authorities in charge of P/ CVE, international organizations, law enforcement agencies, CSOs, and private sector stakeholders can all benefit from a more decentralized engagement framework leveraging municipal structures and capabilities to deliver much needed rehabilitation and reintegration support. For example, the Municipality of Hani i Elezit— one of the municipalities most affected by the phenomenon of foreign fighters in the country—had only one psychologist employed on a short-term contract months after the repatriation of Kosovar nationals in April 2019.66 In fact, several interviews and reports describe a critical shortage of locally-based psychologists in most municipalities.67 Clearly, this is a matter that requires particular attention, starting with providing local authorities needed resources. Developing localized mental health capacities will be critical for providing timely and comprehensive medical and social support to repatriated children and women affected by PTSD in the mid-to-long term. Capacity for the provision of other services, like vocational training and social services will also need to be scaled up.

This investment in boosting localized capacities will require some time, but a good starting point would be developing municipal or region-specific P/CVE plans that would prioritize rehabilitation and reintegration initiatives, allocating some initial government resources, and working with international organizations to identify additional funding streams. There are already some emerging good practices from similar sub-national efforts that may be useful in the context of Kosovo.68

Recommendations

As a Kosovar inter-ministerial working group is drafting a revised CVE strategy and action plan for countering terrorist radicalization and recruitment, this report took stock of good practices and lessons learned from initial efforts for the rehabilitation and reintegration of returning children and women from Syria, reflected on ongoing challenges affecting their implementation, and identified possible opportunities for more inclusive partnerships and sustainable rehabilitation and reintegration outcomes. Below are a number of overarching recommendations that policymakers should consider:

Integrate representatives of local government and CSOs in the development of the revised national CVE strategy and action plan. By allowing a more meaningful role for local government authorities and leveraging the expertise of community-based organizations at the national policy and strategy development level, it is possible to design an organic model of rehabilitation and reintegration that can utilize more efficiently the local capacities and facilitate more sustainable local solutions. Building strategic multi-sectoral partnerships is particularly convenient in times of economic hardship and inadequate resources. The integration of top-down and bottom-up approaches on rehabilitation and reintegration broadens the spectrum of options.

Support the development of tailored municipal/regional rehabilitation and reintegration plans aligned with the strategic priorities of the national CVE strategy. This partially decentralizing feature of the strategy will foster increased engagement and ownership of the rehabilitation and reintegration efforts at the local level. The approach would help gradually transition some of the core efforts from technical staff housed in the capital city to the municipalities where returnees reside. Locally based practitioners like psychologists and social workers would be more accessible to returnees, the services more consistent, predictable, and cost-efficient. If provided adequate resources and personnel, these municipal institutions can be gradually transformed into vibrant hubs for the coordination of multi-stakeholder rehabilitation and reintegration initiatives, delivery of services, and sharing best practices across Kosovar municipalities.

Provide repatriated families with adequate financial assistance and opportunities for economic stability in order to avoid further radicalization. The returnees are vulnerable, traumatized, and in some cases radicalized. Often a woman caretaker of multiple children has to rely on a monthly welfare check that is insufficient to meet the basic needs of the family. This precarious socio-economic situation is more likely to lead to marginalization and possible radicalization than reintegration. Particular attention should be given to teenage returnees in stressful situations, who may be more vulnerable and possibly become target of radicalization networks.

Create a multi-agency childcare system and provide personalized long-term care for child returnees. The initial psychosocial evaluations of repatriated children by the mental health team revealed clear symptoms of PTSD. Prolonged exposure to extreme violence and traumatic experiences affects the psychological wellbeing of children in different ways. Their treatment requires an individualized, timely, and precise assessment of needs differentiating between age, gender, type of trauma, and exposure. Some countries have developed assessment systems with detailed information about the child’s background, exposure to violence, family relations, type of support required, etc, in order to tailor the long-term treatment. The consensus is that the child’s well-being, needs, vulnerabilities, and possible risk factors should be assessed concurrently and addressed continuously via multi-agency cooperation, including child protection and law enforcement agencies.

Develop a communications strategy for engagement with receiving communities and the press on the rehabilitation and reintegration of returnees and P/CVE efforts in general. Pre-repatriation polls revealed a considerable number of respondents opposed to the repatriation of citizens from Syria and reluctance to accept them in Kosovar communities. In order to discourage negative and stigmatizing messaging against returnees, and potential resentment linked to any assistance they may be receiving— especially in communities facing chronic economic challenges—it is important for central and local government officials to adopt a clear public engagement strategy. They should communicate to the public clearly, sufficiently, and consistently the benefits of the returnees’ rehabilitation and reintegration to the whole Kosovar society. The goal should be to manage the public discourse on returnees, use positive narratives, provide updates of government efforts, and inform the public about any positive progress in order to assuage concerns and foster support for successful reintegration.

Additional Relevant Readings

“Ankara Memorandum on Good Practices for a Multi-Sectoral Approach to Countering Violent Extremism” by the Global Counterterrorism Forum. 13 September 2019.

“Good Practices on Addressing the Challenge of Returning Families of Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs)” by the Global Counterterrorism Forum. 25 November 2018.

“Best Practices for Supporting the Reintegration and Rehabilitation of Chidlren from Formerly ISISControlled Territories.” By Mia Bloom and Heidi Ellis. Minerva Research Initiative. 15 July 2020.

“Children affected by the foreign-fighter phenomenon: Ensuring a child rights-based approach.” By the UN Counterterrorism Center. September 2018.

“A Roadmap to Progress: the state of the Global P/CVE Agenda”. By RUSI and the Prevention Project. 24 September 2018.

“Enhancing Civil Society Engagement.” By Global Center on Cooperative Security. July 2020.

“Ex Post Paper: High-Level Conference on child returnees and released prisoners.” By RAN Centre of Excellence. 2018.

“Rapid Review to Inform the Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Child Returnees from the Islamic State.” By Stevan Weine, Zachary Brahmbatt, Emma Cardeli, Heidi Ellis. Boston College. 19 June 2020.

“The Reintegration Imperative: Child Returnees in the Western Balkans.” By Adrian Shtuni. Resolve Network. February 2020.

“Key principles for the protection, repatriation, prosecution, rehabilitation and reintegration of women and children with links to United Nations-listed terrorist groups.” By the United Nations. April 2019.

“The Role of Civil Society in Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism and Radicalization that Lead to Terrorism.” OSCE. August 2018

Footnotes

- Note: For more on the dynamics of radicalization and drivers of violent extremism in Kosovo read: Shtuni, Adrian. “Dynamics of Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Kosovo.” USIP, December 2016. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR397-Dynamics-of-Radicalization-and-Violent-Extremism-in-Kosovo.pdf and IRI. “Understanding Local Drivers of Violent Extremism in Kosovo.” Spring 2017. https://www.iri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2017-9-17_kosovo_vea_report.pdf

- Shtuni, Adrian. “Western Balkans Foreign Fighters and Homegrown Jihadis: Trends and Implications.” CTC Sentinel, August 2019. https://ctc.usma.edu/western-balkans-foreign-fighters-homegrown-jihadis-trends-implications/

- Bytyci, Fatos. “Kosovo Brings Back Fighters, Families of Jihadists from Syria,” Reuters, April 20, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kosovo-syria/kosovobrings-back-fighters-families-of-jihadists-from-syria-idUSKCN1RW003

- Note: The data in this report referring to Kosovar citizens who traveled to Syria and Iraq, returned independently, or were repatriated by the Kosovar government during the relevant timeframe was provided or released by Kosovar law enforcement agencies

- Shtuni, Adrian. “Dynamics of Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Kosovo.” USIP, December 2016. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR397-Dynamics-of-Radicalization-and-Violent-Extremism-in-Kosovo.pdf

- Note: It is likely that some individuals may have relocated to other countries

- Note: Including Kosovar citizens who traveled to Syria and Iraq or were born in the conflict theater and excluding those who have been reported killed or have died of natural causes.

- Trisko Darden, Jessica; Henshaw, Alexis; and Szekely, Ora. “Insurgent women: Female Combatants in Civil Wars.” Georgetown University Press. 2019; Bloom, Mia. “Bombshell.” University of Pennsylvania Press. 2011; Moaveni, Azadeh. “Guest House for Young Widows: Among the Women of ISIS.” Random House. 2019; Moser, Caroline O. N. and Clark, Fiona C. “Victims, Perpetrators or Actors? Gender, armed conflict and political violence.” Zen Books. 2001.

- Saltman, Erin Marie and Smith, Melanie. “Till Martyrdom do us part: Gender and the ISIS phenomenon.” Institute for Strategic Dialogue. 2015. https://icsr.info/ wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ICSR-Report-%E2%80%98Till-Martyrdom-Do-Us-Part%E2%80%99-Gender-and-the-ISIS-Phenomenon.pdf

- Gardner, Frank. “The crucial role of women within the Islamic State.” BBC online. 19 August 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-33985441

- Cook, Joana and Vale, Gina. “From Daesh to “Diaspora”: Tracing the women and minors of Islamic State.” International Centre for the Study of Radicalization. 2018. https://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ICSR-Report-From-Daesh-to-%E2%80%98Diaspora%E2%80%99-Tracing-the-Women-and-Minors-of-Islamic-State. pdf

- Note: Mujahidat were female companions of prophet Muhammad who fought alongside him.

- Moaveni, Azadeh. “ISIS Women and Enforcers in Syria Recount Collaboration, Anguish and Escape.” The New York Times. 21 November 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/22/world/middleeast/isis-wives-and-enforcers-in-syria-recount-collaboration-anguish-and-escape.html

- Vale, Gina. “Women in Islamic State: From Caliphate to Camps.” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague. October 2019. https://icct.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Women-in-Islamic-State-From-Caliphate-to-Camps.pdf

- Washington Post & Mekhennet, Souad and Warrick, Joby. “ISIS brides returning home and raising the next generation of jihadist martyrs.” National Post Online. 27 November 2017. https://nationalpost.com/news/world/isis-brides-returning-home-and-raising-the-next-generation-of-jihadist-martyrs

- Singer, P. W. “Children at War.” University of California Press. 2006

- Winter, Charlie and Margolin Devorah. “The Mujahidat Dilemma: Female Combatants and the Islamic State.” CTC Sentinel. August 2017. https://ctc.usma.edu/ the-mujahidat-dilemma-female-combatants-and-the-islamic-state/

- Cook, Joana and Vale, Gina. “From Daesh to “Diaspora”: Tracing the women and minors of Islamic State.” International Centre for the Study of Radicalization. 2018. https://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ICSR-Report-From-Daesh-to-%E2%80%98Diaspora%E2%80%99-Tracing-the-Women-and-Minors-of-Islamic-State. pdf

- Human Rights Watch. “Syria: Dire Conditions for ISIS Suspects’ Families.” 23 July 2019. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/23/syria-dire-conditions-isis-suspects-families

- Sherlock, Ruth. “Islamic State carry out mass execution inside Palmyra ruins.” The Telegraph Online. 05 July 2015. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/ islamic-state/11718341/Islamic-State-carry-out-mass-execution-inside-Palmyra-ruins.html

- Horgan, John G.; Taylor, Max; Bloom, Mia and Winter, Charlie. “From Cubs to Lions: A Six Stage Model of Child Socialization into the Islamic State, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism.” 2017.

- Singer, P. W. “Children at War.” University of California Press. 2006. and Horgan, John G.; Taylor, Max; Bloom, Mia and Winter, Charlie. “From Cubs to Lions: A Six Stage Model of Child Socialization into the Islamic State, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism.” 2017.

- Ibrahim, Azeem and François, Myriam. “Foreign ISIS Children deserve a home.” International Observatory of Human Rights. 8 September 2020. https://observatoryihr.org/blog/foreign-isis-children-deserve-a-home/

- Mehra, Tanya and Paulussen, Christophe. “The Repatriation of Foreign Fighters and Their Families: Options, Obligations, Morality and Long-Term Thinking.” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague. 6 March 2019. https://icct.nl/publication/the-repatriation-of-foreign-fighters-and-their-families-options-obligations-morality-and-long-term-thinking/

- Open Letter from National Security Professionals to Western Governments. “Unless we act now, the Islamic State will rise again.” The Soufan Center. 11 September 2019. https://thesoufancenter.org/open-letter-from-national-security-professionals-to-western-governments-unless-we-act-now-the-islamic-state-will-rise-again/

- NOTE: See for example UN Security Council Resolution 2178 and 2396, the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

- Office of the Prime Minister. Republic of Kosovo. “Strategy on prevention of violent extremism and radicalization leading to terrorism, 2015-2020.” September 2015. https://wb-iisg.com/wp-content/uploads/bp-attachments/6122/STRATEGY-on-PVERLT_parandalim_-_ENG.pdf

- Ahmeti, Gentiana. “Qeveria voton emërimin e Kordinatorit Nacional për luftimin e terrorizmit.” Kallxo.com. 14 July 2020. https://kallxo.com/lajm/qeveria-voton-emerimin-e-kordinatorit-nacional-per-luftimin-e-terrorizmit/

- Ministry of Interior. Republic of Kosovo. “Division of prevention and reintegration of radicalized people.” https://mpb.rks-gov.net/f/78/

- Bureau of Counterterrorism. U.S. Department of State. “Country Reports on Terrorism 2019: Kosovo.” 2019. https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2019/kosovo/

- Deutche Welle Albania. “Dr. Valbona Tafilaj: We are taking all possible steps in Kosovo to reintegrate returnees from the Islamic State.” 21 October 2019. https:// www.facebook.com/watch/?v=529797967811819

- Wolfe, Sarah and Orozobekova, Cholpon. “Lessons Learned from Kazakhstan’s Repatriation and Rehabilitation of FTFs.” Bulan Institute for Peace Innovations. 06 May 2020. https://bulaninstitute.org/lessons-learned-from-kazakhstans-repatriation-and-rehabilitation-of-ftfs/

- Ashimov, Aydar. “US praises “groundbreaking” Kazakh repatriation process of IS returnees.” Caravanserai. 16 October 2019. https://central.asia-news.com/en_GB/ articles/cnmi_ca/features/2019/10/16/feature-01

- Gonzales, Paule. “95 minors of jihadists have returned in France since 2015.” Le Figaro online. 29 March 2019. https://www.lefigaro.fr/actualitefrance/2019/03/29/01016-20190329ARTFIG00135-la-france-a-rapatrie-95-enfants-de-djihadistes-depuis-2015.php

- Méheut, Constant and Hubbard, Ben. “France Brings 10 Children of French Jihadists Home from Syria”. The New York Times online. 22 June 2020. https://www. nytimes.com/2020/06/22/world/europe/france-isis-children-repatriated.html

- ibid

- Gonzales, Paule. “95 minors of jihadists have returned in France since 2015.” Le Figaro online. 29 March 2019. https://www.lefigaro.fr/actualitefrance/2019/03/29/01016-20190329ARTFIG00135-la-france-a-rapatrie-95-enfants-de-djihadistes-depuis-2015.php

- Qenaj, Taulant. “Treating the trauma of returnees from Syria.” Radio Free Europe. 30 October 2019. https://www.evropaelire.org/a/te-kthyerit-nga-siria-trajtim-/30244065.html

- Deutche Welle Albania. “Dr. Valbona Tafilaj: We are taking all possible steps in Kosovo to reintegrate returnees from the Islamic State.” 21 October 2019. https:// www.facebook.com/watch/?v=529797967811819

- Voice of America. “Kosovo: Challenges of integrating women returnees from Syria.” 29 February 2020. https://www.zeriamerikes.com/a/5309685.html

- Ruf, Maximilian and Jansen, Annelies. “Study visit: Returned women and children – studying an ongoing experience on the ground.” 20 December 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/ran-papers/docs/ran_study_visit_kosovo_11_10122019_en.pdf

- ibid

- Kosovar Center for Security Studies. “#Pristina – Discussing about Reintegration and the Role of Communities in this Process.” 12 August 2020. https://www. facebook.com/KCSSQKSS/videos/927985824380463

- Ruf, Maximilian and Jansen, Annelies. “Study visit: Returned women and children – studying an ongoing experience on the ground.” 20 December 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/ran-papers/docs/ran_study_visit_kosovo_11_10122019_en.pdf

- Voice of America. “Kosovo: Challenges of integrating women returnees from Syria.” 29 February 2020. https://www.zeriamerikes.com/a/5309685.html

- Office of the National Coordinator for Countering Violent Extremism and Terrorism. Republic of Kosovo. “Evaluation of the Strategy on Prevention of Violent Extremism and Radicalization Leading to Terrorism (2015-2020).” January 2020

- Radio Free Europe. “Woman returned from Syria gets to two and a half years suspended sentence.” 03 September 2019. https://www.evropaelire.org/a/30144132. html

- Partners Kosova. Center for Conflict Management. Facebook.com/partnerskosova

- Kosovar Centre for Security Studies. “Youth for Youth: Increasing resilience among the vulnerable youth in Kosovo.” http://www.qkss.org/en/Current-projects/ Youth-for-Youth-increasing-resilience-among-the-vulnerable-youth-in-Kosovo-1299

- Qenaj, Taulant. “Rehabilitation of returnees from Syria deteriorate due to coronavirus.” https://www.evropaelire.org/a/te-kthyerit-siria-koronavirusi-rehabilitimi/30739515.html

- Pantucci, Raffaello. “A View from the CT Foxhole: Gilles de Kerchove, European Union (EU) Counter-Terrorism Coordinator.” CTC Sentinel. August 2020. https:// ctc.usma.edu/a-view-from-the-ct-foxhole-gilles-de-kerchove-european-union-eu-counter-terrorism-coordinator/

- Bureau of Counterterrorism. U.S. Department of State. “Country Reports on Terrorism 2019: Kosovo.” https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2019/kosovo/

- Ruf, Maximilian and Jansen, Annelies. “Study visit: Returned women and children – studying an ongoing experience on the ground.” 20 December 2019. https:// ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/ran-apers/docs/ran_study_visit_kosovo_11_10122019_ en.pdf

- Shtuni, Adrian. “Western Balkans Foreign Fighters and Homegrown Jihadis: Trends and Implications.” CTC Sentinel, August 2019. https://ctc.usma.edu/western-balkans-foreign-fighters-homegrown-jihadis-trends-implications/

- Sejdiu, Erblina. “Video: Planning terrorist acts against KFOR, clubs in Gracanica and an Orthodox church, got them sentenced to 25 years in prison.” Kallxo. Com. 04 September 2019. https://kallxo.com/ligji/planifikonin-sulme-terroriste-ndaj-kfor-it-diskotekave-ne-gracanice-dhe-kishes-ortodokse-denohen-me-25-vite-burgim/

- Shala, Gzim. “Seven accused on terrorism charges get sentenced to over 18 years in prison, one’s charges were dropped.” Betimiperdrejtesi.com. 17 July 2018. https://betimiperdrejtesi.com/denohen-me-mbi-15-vjet-burg-shtate-te-akuzuarit-per-terrorizem-njeri-lirohet-nga-akuza/

- Shtuni, Adrian. “Dynamics of Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Kosovo.” USIP. 19 December 2016. https://www.usip.org/publications/2016/12/dynamics-radicalization-and-violent-extremism-kosovo

- Kelmendi, Vese. “KSB Special Edition: Citizens perceptions on new threats of violent extremism in Kosovo.” Kosovar Centre for Security Studies. 12 February 2019. http://www.qkss.org/en/Reports/KSB-Special-Edition-Citizens-perceptions-on-new-threats-of-violent-extremism-in-Kosovo-1196

- Odoxa.fr. “The French massively approve the judgment of jihadists by Iraq and don’t want to see their children returned.” 28 February 2019. http://www.odoxa.fr/ sondage/djihadistes-francais-approuvent-massivement-jugement-lirak-ne-veulent-voir-leurs-enfants-revenir/

- Holmer, Georgia and Shtuni, Adrian. “Returning Foreign Fighters and the Reintegration Imperative.” USIP. March 2017. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/ files/2017-03/sr402-returning-foreign-fighters-and-the-reintegration-imperative.pdf

- Pantucci, Raffaello. “A View from the CT Foxhole: Gilles de Kerchove, European Union (EU) Counter-Terrorism Coordinator.” CTC Sentinel. August 2020. https:// ctc.usma.edu/a-view-from-the-ct-foxhole-gilles-de-kerchove-european-union-eu-counter-terrorism-coordinator/

- International Monetary Fund. “Republic of Kosovo: Country data.” April 2020. https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/KOS

- OSCE. “The Role of Civil Society in Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism and Radicalization that Lead to Terrorism.” August 2018. https://www.osce.org/ files/f/documents/2/2/400241_1.pdf

- Nemr, Christina and Bhulai, Rafia. “Civil Society’s role in rehabilitation and reintegration related to violent extremism.” IPI Global Observatory. 25 June 2018. https://theglobalobservatory.org/2018/06/civil-societys-role-rehabilitation-reintegration-violent-extremism/

- Office of the National Coordinator for Countering Violent Extremism and Terrorism. Republic of Kosovo. “Evaluation of the Strategy on Prevention of Violent Extremism and Radicalization Leading to Terrorism (2015-2020).” January 2020

- Ahmeti, Adelina. “Alarm bells from Hani i Elezit: there are no funds to deal with extremism in the municipality.” Kallxo.com. 27 July 2019. https://kallxo.com/gjate/ alarmi-nga-hani-i-elezit-komuna-pa-fonde-per-trajtimin-e-ekstremizmit/

- ibid

- Rosand, Eric and Skellett, Rebecca. “Connecting the Dots: Strengthening National-Local Collaboration in Addressing Violent Extremism.” Lawfare Institute. 21 October 2018. https://www.lawfareblog.com/connecting-dots-strengthening-national-local-collaboration-addressing-violent-extremism