Shah, a candidate in Monday’s national elections, was at a rally here in the Pakistani capital in July when a massive bomb exploded, killing 19 people and injuring 90. The blast took off Shah’s legs. But it did not kill his desire to be part of the political process.

For the past six months, he has gone door-to-door in a wheelchair, delivered fiery speeches at political rallies and even held a baby or two at a mall. “My life is now a protest. I want to be a role model for the people,” he said in an interview this past week. “If I don’t do this, how can I say anything about the future of Pakistan?”

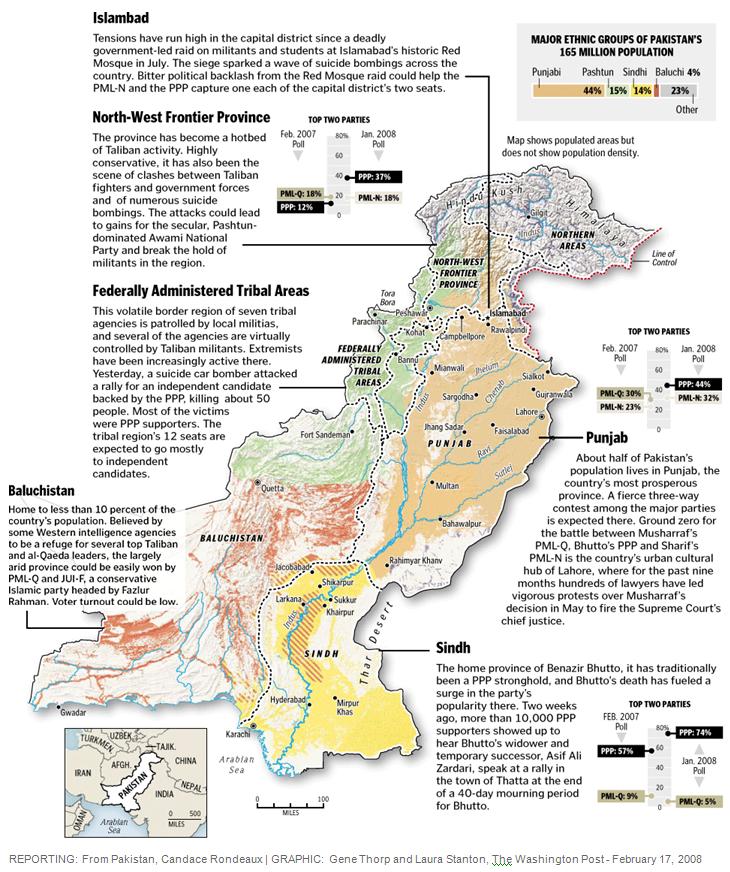

It is hardly surprising that the parliamentary elections, the first here in five years, have engendered such lofty statements. For the past year, this turbulent nation of 165 million has lurched from one political crisis to another under the government of President Pervez Musharraf. This vote will help decide its fate.

“It’s going to determine the future of the region,” said Talat Masood, a retired Pakistani general and political analyst. “It’s a question of whether in a Muslim country there can be democracy. It’s a question of whether a nuclear-armed nation can coexist peacefully with its neighbor, in this case India.”

MAP: Pakistan’s Elections

Votes cast in tomorrow’s legislative elections could reshape the political landscape of this increasingly turbulent nation. President Pervez Musharraf is not up for the election, but his party’s grip on power is tenuous. A possible alliance between the two largest opposition parties could lead to Musharraf’s ouster or a prolonged political standoff in Parliament.

Although Musharraf’s presidency is not immediately threatened, he could be vulnerable to impeachment if opposition parties win a two-thirds majority. More broadly, the elections are being viewed by many people as a referendum on his rule. Musharraf’s popularity has plummeted to an all-time low, not least because of his cooperation with U.S. counterterrorism efforts.

Pakistan has a history of flawed elections, including the last round in 2002, but Musharraf has vowed repeatedly that this time the vote will be “free, fair and transparent.” Opposition candidates have said they have little confidence in the president’s pledges and predict that rigging will fuel further instability.

There are also security fears. As many as 90 people have been killed in Pakistan in the past week alone in suicide bombings targeting opposition rallies, including a blast Saturday in the tribal agency of Kurram that left dozens of people dead. The bombings are believed to be the work of religious extremists, against whom the Pakistani government has waged a protracted war.

The most prominent victim of those extremists has been opposition leader Benazir Bhutto, whose assassination less than two months ago in northern Pakistan led the government to postpone elections. Polls suggest that under the leadership of Bhutto’s widower, Asif Ali Zardari, her Pakistan People’s Party will fare well Monday.

Last week, an estimated 10,000 of the party’s supporters gathered at a stadium in the eastern city of Faisalabad for a rally. Despite stifling heat, the crowd remained boisterous as Zardari, fist in the air, led a chant calling for his party to take a two-thirds majority in Parliament and oust Musharraf. Zardari pointed to a house near the edge of the stadium where several government sharpshooters stood on the roof with rifles at the ready.

“Do not be afraid of them,” he said. “If we are afraid of them today, then our children will be slaves in the future.”

Many candidates, less bold than Zardari, have eschewed public campaigning because of security concerns.

Pakistan’s Elections

Votes cast in tomorrow’s legislative elections could reshape the political landscape of this increasingly turbulent nation. President Pervez Musharraf is not up for the election, but his party’s grip on power is tenuous. A possible alliance between the two largest opposition parties could lead to Musharraf’s ouster or a prolonged political standoff in Parliament.

Aftab Khan Sherpao, a former interior minister under Musharraf who was the target of two suicide bombings last year, said the risk was too great. “I ran most of my election campaign from my home because it’s hard to go out and meet with the voters,” he said.

A longtime Bhutto supporter who angered extremists by backing military operations in Pakistan’s tribal areas, Sherpao is running for a seat in the town of Charsadda, in North-West Frontier Province, as is his son. Sherpao expressed pessimism about people turning out to vote. “It’s pretty hard to bring them out on election day because of the fear of suicide attacks and other acts of terrorism,” he said.

The government has deployed more than 50,000 security personnel at polling stations across North-West Frontier Province alone. To the southwest, officials in the tribal areas that border Afghanistan have declared all 1,122 polling stations to be at “high risk” for attacks.

Violence has already tilted the odds against some candidates. In North-West Frontier Province, some religious parties have lost luster because of bombings, and secular parties such as the Awami National Party are resurgent. One major religious party has declared a boycott of the elections as a protest against government-led attacks on radical Islamic fighters.

Polls, meanwhile, portend a strong showing by the Pakistan People’s Party in Punjab province and in the southern province of Sindh. In Punjab, where more than half the country’s 80 million eligible voters live, the party will be competing mainly with the party of former prime minister Nawaz Sharif. The two parties could form an alliance, although it might prove short-lived since their only shared goal is Musharraf’s ouster.

Analysts acknowledge that the possibility of vote-rigging makes predictions of any kind unreliable. In recent days, Western political analysts and election observers have complained bitterly about the ruling party’s handling of the elections.

Kanwar Dilshad, secretary general of the Election Commission of Pakistan, said Friday that he had met with several representatives of international election observer groups to hear their concerns about rigging. He denied claims that observers had encountered resistance from the Pakistani government.

“The observers are our guests,” Dilshad said. “The Pakistani people are always very kind to their guests and are always good about hosting. We will host them, and we will accommodate them.”

Even if some rigging does occur, the opposition parties are expected to capture from half to two-thirds of the 342 seats in the National Assembly.

Anything short of that, analysts here say, would raise suspicions of major rigging and be likely to plunge Pakistan into deeper chaos.

The recently appointed army chief, Gen. Ashfaq Kiyani, could be forced to order military intervention.

Many opposition supporters have vowed to take to the streets at the first sign of rigging. Candidates, too, said they would contest the results if they appeared unfair.

“I’ll just protest in the road,” Shah said, banging the side of his wheelchair with his shrapnel-scarred right hand. “What can they do — throw me in jail?”

A few minutes later, one of Shah’s assistants lifted him into a waiting car, and his convoy set out for a nearby rally.

Correspondent Pamela Constable in Lahore and special correspondent Imtiaz Ali in Peshawar contributed to this report.

Top