The times do not seem to be ripe for European leaders to organize referendums.

After the spectacular backfire caused by the Brexit referendum (which cost Prime Minister David Cameron his career), and a half-victory for Viktor Orbán on a referendum of migrants quota that he was expected to fully win, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi had to resign after comprehensively losing an institutional referendum. “Another one bites the dust”, some would say. However, in Italy more than anywhere else, one should not judge the book by its cover: although Sunday’s results were a clear blow to Renzi, it does not mark the end of his career, nor Italy’s exit from Europe as some have commented.

To understand what is going on in Rome today, one should remember what the referendum was all about – and it was about anything but the European Union. Earlier this year, while he was at the height of his popularity but could not gather the two-third majority needed in parliament, Matteo Renzi decided to appeal directly to the people to support his project for constitutional reform. The project aimed at ending the “perfect bicameralism” put in place after 1945, at a time in which the possibility of hardcore communists taking power through elections led the Italian elites to produce a very complex set of checks and balances to ensure Italy’s firm engagement in the West. Attempts at reform had already been made since the mid-1980s, but Renzi’s plan was probably the boldest, as it proposed to castrate the senate by weakening its legitimacy: under the projected change, the upper house would have gone from 315 directly elected members to just 100 nominated senators (95 by regional councils, and 5 by the President of the Republic). As a result, the Senate would have lost many of its powers and would have become a mostly consultative body, turning Italy from a perfectly bicameral republic to a de facto unicameral system. In turn the expected result was to make far-reaching and ambitious reforms easier in Italy, a necessary step as the country missed the train of globalization and was hit particularly hard by the 2008 financial crisis.

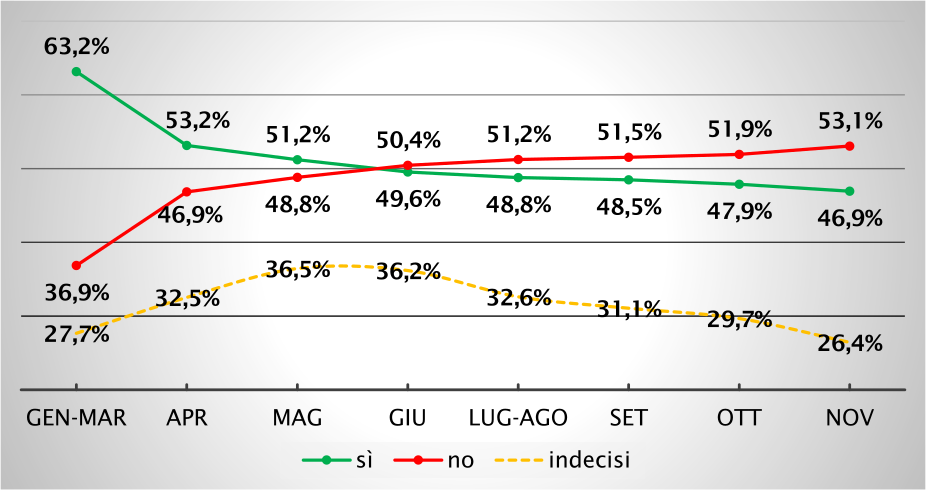

When Renzi called the referendum, he remained very popular and therefore linked his own political career to the results. That was a mistake that not only transformed the vote into a plebiscite around his person, but also a miscalculation as his political fortunes took a turn for the worst during the year, thereby dragging down support for him and the reform. As polling aggregates evolution suggests, the tipping point was the June 2016 local election, which marked a clear defeat for Renzi’s Democratic Party and very symbolic wins in the two most important cities of the country for the anti-systemic Five Star Movement (M5S) lead by former comedian Beppe Grillo. These results seem to have provided the “no” camp with a positive dynamic that was never to disappear, despite Renzi’s efforts to reverse the trends throughout the autumn.

However, linking the results of the referendum solely to the rise of Grillo and right-wing populism in Italy is a fundamental mistake. The fact is that the “no” camp gathered supporters from all camps, included Renzi’s political family, and these supporters voted for very different reasons: some people, mostly liberals and centrists (including newspapers and magazines like The Economist), campaigned and voted for the “no” because they felt that the change of institutions would lead to a dangerous concentration of powers. Regionally-based movements voted “no” because they feared that a toothless senate would reinforce the hand of Rome against the regions, while for left-wingers as well as right-wingers, the vote was clearly a way to show a middle-finger at the establishment and to put Renzi in difficulty. In all, the “no” camp gathered very different people such as Forza Italia’s leader Silvio Berlusconi, M5S’ Beppe Grillo, Northern Italian nationalist Matteo Salvini, but also prominent members of Renzi’s own political family, such as former Prime Minister Massimo D’Alema. The coalition was indeed one of establishment and anti-establishment personalities and interests, which made it in the end too formidable to beat.

As he had promised at the beginning of the campaign, Matteo Renzi almost immediately announced his resignation as Prime Minister. The question is now what happens in Italy after a result that must be seen as a clear slap in the face of the soon-to-be-former Prime Minister. In political terms, the most likely scenario as of now is the forming of a technical government that will probably prepare for anticipated elections in 2017 (although it could try and keep up another year to finish parliament’s mandate until 2018). In that case, and despite a continued atomization of the Italian party system, the political split will probably be marked by a confrontation between an anti-system pole led by Beppe Grillo’s M5S and a centrist pole led by the Democratic Party – and most probably by Matteo Renzi, who will most likely remain its leader despite the current vote, and therefore win back his place as Prime Minister. The choice is likely to be different there: first, the centrists will most likely be much more united than the anti-system vote, which will most likely split between M5S, the Northern nationalist Lega Nord and the Italian nationalist Fratelli d’Italia; second, while the referendum was a plebiscite for or against Renzi, the legislative election will most likely propose a choice as to who should be the Prime Minister: in this configuration, it is not yet clear whether Italian voters will really and purposefully take the risk of electing a leader with no experience in governance, particularly as Beppe Grillo’s local leaders in Rome and Turin are finding it very hard to deliver the positive change they had promised during the local elections.

That feeling might be reinforced by the possible economic difficulties Italy might face in the next few weeks. For if the situation of a technical government is not new to Italy, Renzi’s setback comes at a time of extreme fragility in the Italian banking system, with several banks bordering bankruptcy (most infamously the oldest financial establishment in the world, the Sienese Bank Monte dei Paschi, whose recent rescue is now in doubt). Although most investors have anticipated the “no” in the referendum and the resignation of the Prime Minister (a common occurrence in Italian politics), there is still uncertainty about the capacity of the Italian banks to survive a speculative attack in the next few days. Uncertainty, more likely than collapse, is what will characterize the Italian economy – which means that just like Renzi, one should not bury the Italian economy just yet.

Top