Cuba’s Referendum – Intimidation, Irregularities, and Implications of Abstaining

Raising expectations for some, lowering them for others.

Last June, newly-appointed President Miguel Diaz-Canel revealed Cuba’s government would draft a new constitution, guided by former president Raul Castro, and approve it through a referendum. Private property rights, presidential term limits, and devolving some powers to the subnational level were promises. Diaz-Canel said citizens would have the chance to provide feedback and vote to approve or reject the document.

In a rare show of public dissent, evangelical churches mobilized and successfully eliminated a proposed clause recognizing same-sex marriage. Self-employed workers and artists also mobilized to demand greater freedoms of expression and association, with limited success. Following the end of the citizen consultations in November 2018, the government incorporated some recommendations, amending about half of the original document.

Cuban independent civil society opposed the referendum, viewing it as unlikely to be free or fair. Seeing it as a way to gloss over perennial issues such as being able to directly elect the leadership of the national government and distract people from more structural problems, most civil society groups (CSGs) encouraged people to vote “No” or abstain from voting in the referendum. A significant portion of the electorate, up to 26 percent, heeded their call. So what does this number say about what Cuban citizens think of the new constitution?

The process: a Potemkin referendum?

In open societies, voter turnout is rarely considered to be a defining feature of an election. The United States, for example, has a low turnout when compared to other democracies. In Cuba, due to its opaque system, turnout is often seen as a proxy for regime support. In five elections from 1986 to 2008, Cuba’s turnout was well above 95 percent—likely because of social or political pressure or outright intimidation, even to the point of government affiliated groups going door to door to persuade people to go to the polls. Following dictator Fidel Castro’s death in 2016, a trend began to emerge. The most recent parliamentary elections in 2018 marked a noticeable drop in voter participation, with a turnout of 85.7%.

The referendum continues this trend, with a turnout rate of 84%, according to the Cuban Electoral Commission, Cuba’s election oversight body appointed by the government and tied to the Communist party. Since voting is so tightly controlled, most observers look to a combination of abstention rates, votes against, null votes, and blank votes to get an idea of what people are thinking. What’s clear from the turnout is that 26 percent of the voting age population did not opt for the new constitution. In the lead up to the vote, many observers such as the Cuban Observatory for Human Rights (OCDH), noticed in their polls a substantial support for the ‘No’ vote and many voters who felt undecided. According to their polling, less than 50 percent clearly intended to vote ‘Yes.’

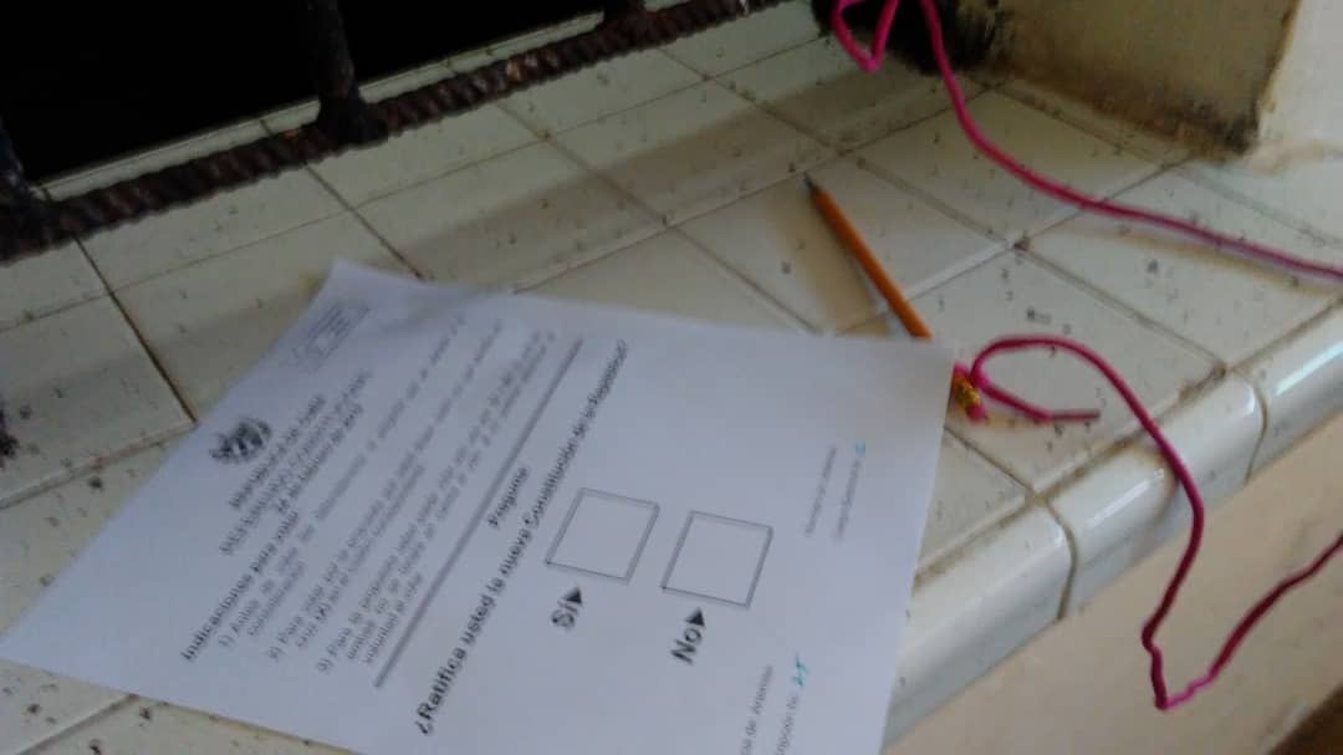

Comparing polling of voter intentions with the data released from the government is complicated. In authoritarian societies research suggests that respondents often give answers the surveyor wants to hear—depending on who they think the surveyor represents. In this case, respondents may have accurately reported how they wanted to vote, but actually voted in line with the government out of fear of reprisal. Secondly, there were widespread reports of intimidation and repression against dissidents and democracy activists that may have scared voters. Finally by some accounts, the electoral commission may have committed fraud changing the numbers to fit their needs. This being Cuba, the government permitted no independent observation of the electoral process from balloting to the vote count. In addition to possibly manipulating the results, there were credible reports of illegal propaganda and shoddy electoral practices, like using pencils instead of ink to mark ballots. The high number of ‘Yes’ votes and the moderately high turnout compared to what OCDH found in their survey could be because the National Electoral Commission (CNE) changed the final tally.

The bottom line:

The constitution does introduce some welcome changes to Cuba. It recognizes private property, opens up the possibility of foreign investment, devolves power and limits the presidential term. Most notably, expanded freedom of assembly and presumption of innocence have the possibility of changing civil society’s role. There are speculations that more changes may be on the horizon following this process.

While it may appear that this referendum gave Cubans the opportunity to choose between two different options, it’s more an example of how the Cuban government controls and intimidates citizens. Independent Cuban civil society made a strong effort to present a united front, despite the odds. They worked hard to urge voters not to approve the new charter. With that in mind, this referendum is a testament to the growing strength of civil society to reach a quarter of Cuban citizens. As Cuba struggles to respond to natural disasters, a flailing economy, and poor governance, civil society has an opportunity to expand its influence.

Top