During the municipal elections in my hometown a couple of years ago, I left work early and went downtown to vote. I presented my ID, the poll workers smiled, and I went to a booth. I recognized the names on the ballot from campaign ads around town and my research. If I didn’t like any of the candidates, I could write in another name. Had I been so inclined, I could have even participated freely in campaigning for one person or another.

On November 26, Cubans will have a very different experience. Instead of having the opportunity to vote, they will select from a pool of candidates already chosen by the government. The Cuban government actively works to give the impression of a democratic process while controlling the outcome of the process and clamping down on dissent.

The Context:

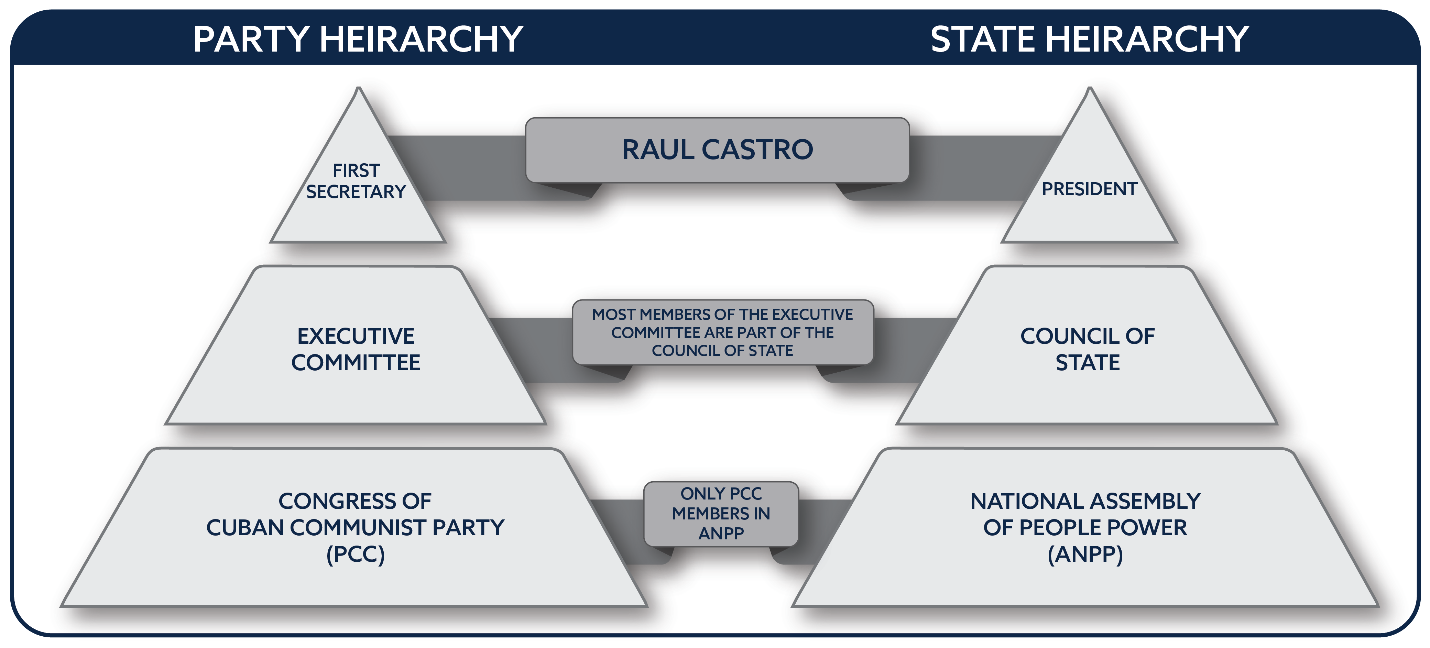

In 2013, Raul Castro announced that he would step down from the presidency of the Council of State in 2018 and promised a series of reforms to the Cuban electoral system. These reforms, such as term limits on the highest offices, how long the National Assembly meets, and potentially allowing candidate campaigning have not been implemented. Since then, observers have speculated what will come next. Raul has talked of a transition of power to someone outside the Castro family. Many wonder whether this would include electoral reform. But, a close look at the system and events show that the Cuban government has no intention of allowing systematic change.

The Process:

The Cuban electoral system is convoluted and tightly controlled. Cuba is a single-party state, which means that the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) is the only legal political party. All senior authorities are also highly ranked PCC officials. And it happens that all highly ranked party officials are also high-ranking military officials, which gives the military a huge role in running the country—a military “deep-state” if you will. The Electoral Commission is closely tied to the central government, which is closely tied to the PCC and the military. Party organs parallel state entities. A voting process that perpetuates such structures would not necessarily promote competition of ideas.

These issues will be front and center November 26, when Cubans “go to the polls.”

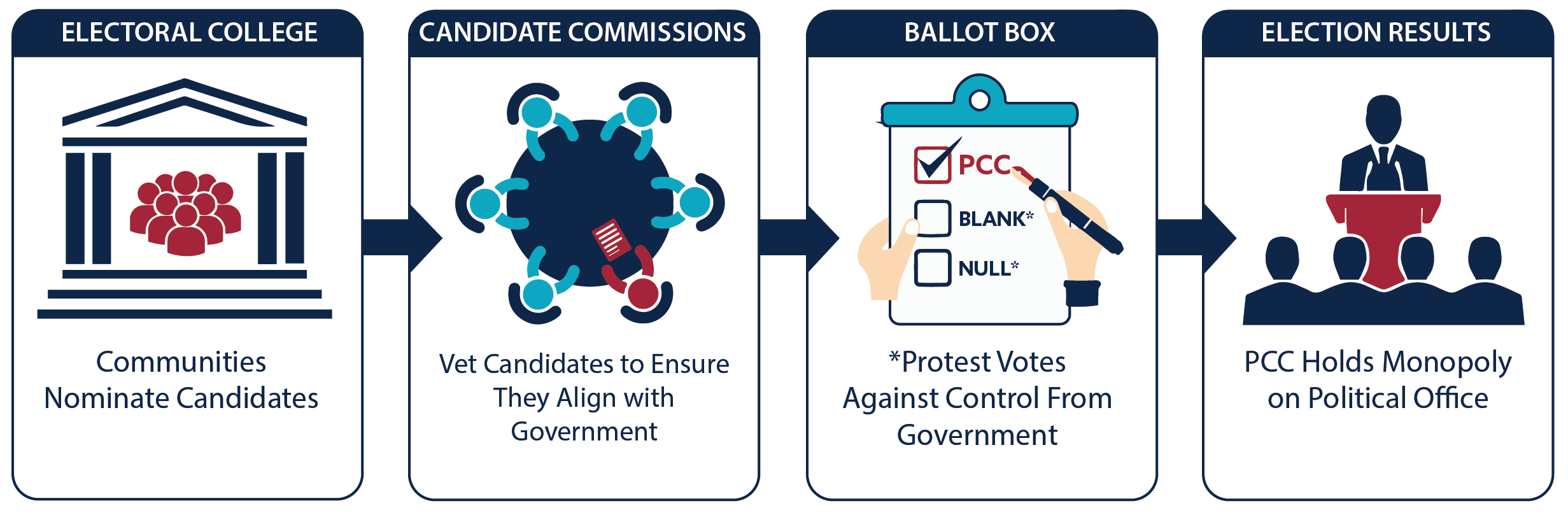

Nominating candidates is the first step in the electoral process. This must be done in a general assembly, called an electoral college, in each municipality. Depending on the size of the municipality, there can be multiple electoral colleges. The local Committee for the Defense of the Revolution or CDR, a neighborhood watch organization created by the Cuban government, is tasked with mobilizing citizens to attend the assembly and making sure dissidents do not agitate the process. Attendance is taken, in part to ensure proper representation, but also to weed out dissidents through threats and intimidation.

Next, candidates that have been nominated in the electoral college are next vetted by a Candidacy Commission. The Commission is one of the most controversial and undemocratic parts of the Cuban electoral process—appointed by the central government and composed of representatives from groups closely linked to the PCC. The Commission evaluates candidates based on qualities like merit, patriotism, ethical values, and revolutionary history. The last bit, revolutionary history, is meant to limit candidacy to citizens who conform to the party line. The Candidacy Commissions are the government’s fail-safe– even if dissidents have acquired popularity and make it to the general assembly, there is still a way for the government to squash their candidacy.

What’s Happening Now:

From mid-September to October 30, general assemblies were held to nominate candidates. More than 60,000 electoral colleges were held resulting in 27,221 approved candidates. In these, 175 candidates linked to a dissident movement called #Otro18 were nominated (the movement’s name being a reference to Raul Castro’s promise to step down in 2018). Fifty-three of 175 made it as far as the Candidacy Commission and were quickly disqualified. Many of the activists were jailed, accused of false charges, and prevented from reaching the assemblies.

In response, opposition platforms are calling on voters to write in “plebiscite” or “Cuba Decides” on the ballot instead of voting for the PCC candidate. This act of defiance would nullify the ballot, meaning it would be discarded. Citizens can also cast a blank vote, meaning they do not choose any of the options. These ballots are also discarded from the total tallies. Given these options, it is no wonder that most are calling this a “selection” instead of an election.

Whatever happens on November 26, the outcome is the “election” of the government’s approved slate of candidates. Everyone already knows the winners.

Top