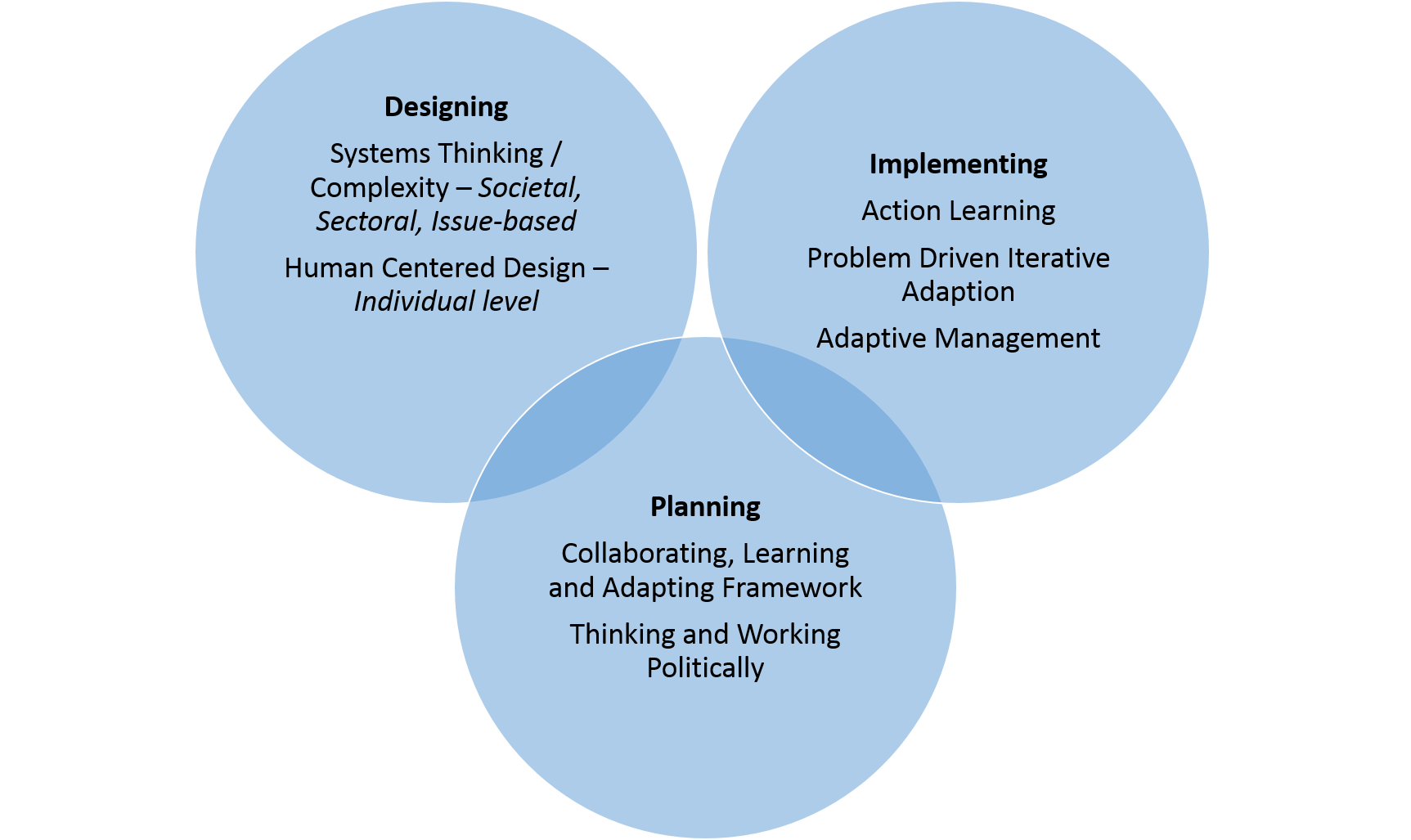

There are a dizzying array of new development ideas and frameworks out there right now.

However, there is some order to all these frameworks and, while there is certainly overlap, you can begin to see commonalities between these frameworks. We can see three broad categories. First, there are designing frameworks related to the factors concerned with how we design programs, this is where systems thinking and human centered design can be useful. Then there are implementing frameworks related to how we operationalize principles when we work through a program; this is where processes such as action learning and adaptive management come in. Finally, there are planning frameworks which provide overarching ways to handle both planning and implementing of programs; this is where ideas such as Collaborating, Learning and Adapting and Thinking and Working Politically come in.

While development ideas do not follow in the academic traditions of presenting an idea, contradicting it and then resolving the tension by means of a synthesis; little attention is often paid to how the two frameworks may complement each other and how we might be able to leverage these insights collectively. Since planning frameworks pertain to both designing and implementing, I will focus on Thinking and Working Politically (TWP) and Collaborating, Learning and Adapting (CLA).

To think and work politically means to integrate analysis of the stakeholder incentives and motivations that are often just assumed when implementing a technical project. In a similar fashion, CLA is a framework that USAID has begun employing to capture three practices: collaborating with partners and stakeholders, learning systematically from our work and putting into place necessary adaptions to make our program works better. While at first they seem to be distinct concepts, these planning frameworks are actually connected in four main ways.

First, programs that have outcomes and impact beyond an individual program require the individuals we work with to be invested in continuing to sustain any changes made. Fundamentally, this first requires active engagement with stakeholders. What does this look like in practice? First, we, especially as outsiders, need to understand the motivations and incentives of the people we are working with. This enables us to design and frame our programs appropriately, detailing how the programs align with their stakeholder as well as potentially avoiding programming that will be difficult to implement or unable to have sustained impact. TWP is an ideal framework to gather and analyze the incentives of stakeholders. For tips on how to do this practically, check out this related blog.

Second, the environments in which development practitioners work are not simple and static. While analyzing the incentives of stakeholders is a natural complement to assessing their needs, these incentives also change over time – even within the relatively short time horizon of many development programs. Motivations that may have been aligned at the beginning may fade away or new incentives may emerge as a result of social, economic or political changes. As such, it is important to ensure that programs can learn and adapt to these changes. The CLA framework therefore supplements the process of how we can integrate the notion of political will not as a one-shot deal but throughout a program’s lifecycle.

Third, development practitioners need to acknowledge that influential stakeholders do not always have a vested interest in achieving your program’s outcomes. While the TWP movement aims at integrating the concept that development solutions require real, resilient political will, the creation of that political will is something that is often the biggest challenge in much of our work. CLA also provides a way to create natural incentives for stakeholders and thus increase the likelihood of success. Evidence suggests that collaborating can effectively improve stakeholder buy-in – for a look at how this works at the team level see this recent blog. Often collaborating can increase the salience of incentives that may be dormant or perceived as less pressing among key stakeholders. CLA offers us a new method by pointing us to potential collaboration with our partners and stakeholders when designing and implementing programs. But there also needs to be processes, such as those captured by collaboration, that are needed to generate and sustain such will during a program.

Lastly, both frameworks provide some practical ways at going about solving complex problems. Many development challenges involve problems where there is little consensus among people over the right solution and it is often unclear what technical approach can fix the problem. Solving these types of collective action challenges requires two things. Programs need to be designed and implemented against a context where the certainty of outcomes and the consensus around the right solution are both unclear. TWP provides a framework to understand how we can leverage the existing patterns of incentives, while CLA suggests an iterative approach that provides a space to testing and prototyping solutions.

While there also be incentives and advantages to having separate development frameworks to better understand how we improve our work, there are even more advantages to seeing the seeing the overlap between ideas and how we can leverage these when designing, planning and implementing our work. Seeing where these synergies exist and how we can design programs appropriately just might be the next big thing in development thinking.

Top