On January 11, the Macedonian Parliament adopted constitutional amendments to add “North” to the country’s name. As part of the Prespa Agreement reached with Greece, Macedonia will become North Macedonia, without affecting the name of its people, who will continue to be called Macedonians.

This was not a decision Macedonians made lightly.

Although Macedonia had formally used this name since 1944, when it was established as a constituent republic in Yugoslavia, Greece had opposed Macedonia’s name since the country’s independence in 1991. Its independence created fear among the Greek political class that Greece would have to recognize the large ethnic Macedonian minority in its northern region and return expropriated property from around 80,000 ethnic Macedonian refugees from the Greek Civil War (1945-1949).

Greece claimed it had exclusive right over the name “Macedonia,” that ancient Macedonia and Alexander the Great were part of its history and as the northern region of Greece is also called Macedonia, the use of the name “Macedonia” by its northern neighbor threatened its territorial integrity. As a result, Greece blocked Macedonia’s potential North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and European Union (EU) accession.

After 27 years of this gridlock, the current Macedonian government conceded that advancing the country’s security and prosperity through accession to these institutions would not happen without compromise.

No Name Compromise, No EU and NATO

For the past three decades, the Macedonia name dispute with Greece had regularly been referenced as the primary obstacle for Macedonian EU and NATO integration. Macedonia has been a candidate for EU membership since 2005, and until 2015, it was continuously granted recommendation by the European Commission to begin negotiations for membership. However, due to the objection by Greece, the European Council, which requires unanimous consent to make decisions, never followed through on this recommendation.

The problem was even more straightforward in the case of NATO. During the 2008 Bucharest Summit, Croatia, Albania and Macedonia were expected to receive an invitation to join the Alliance. Despite confidence and support by world leaders, including U.S. President George Bush, Albania and Croatia were invited to join while Macedonia was left out.

Ten years later, NATO’s Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg bluntly stated to Macedonians, “There is no way to join NATO without changing the name.”

The Macedonian government weighed two options. Either Macedonia could accept some compromise on its name and, in exchange, move closer to NATO and EU accession. Or Macedonia could not budge on their name and remain apart from NATO and the EU. Macedonia’s exclusion from the EU and NATO has been a key concern for ensuring the long-term security of the country and a major deterrent for foreign investments.

The political instability of the country has hindered economic development and prevented the economy from functioning at a normal pace. In the past several years, Macedonia experienced its deepest political crisis, which eroded the rule of law and democratic standards. Many observers point to 2008 as the start of this downward spiral.

EU and NATO, High Desire and a High Price

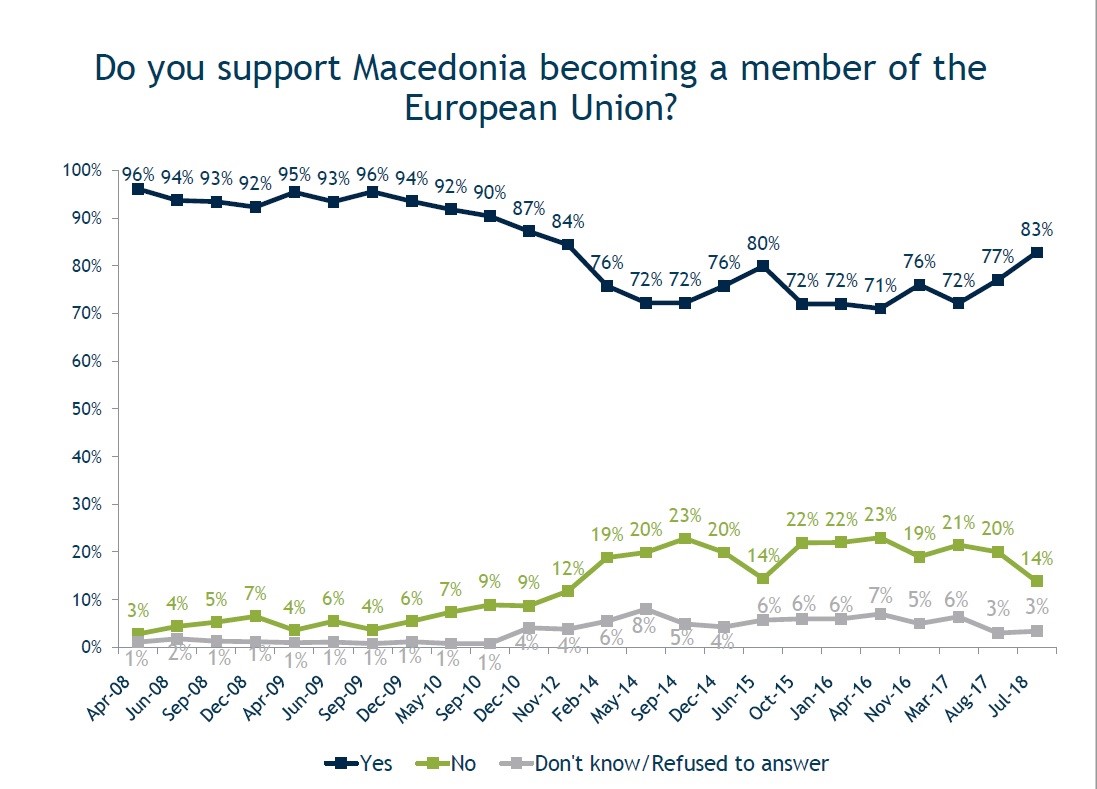

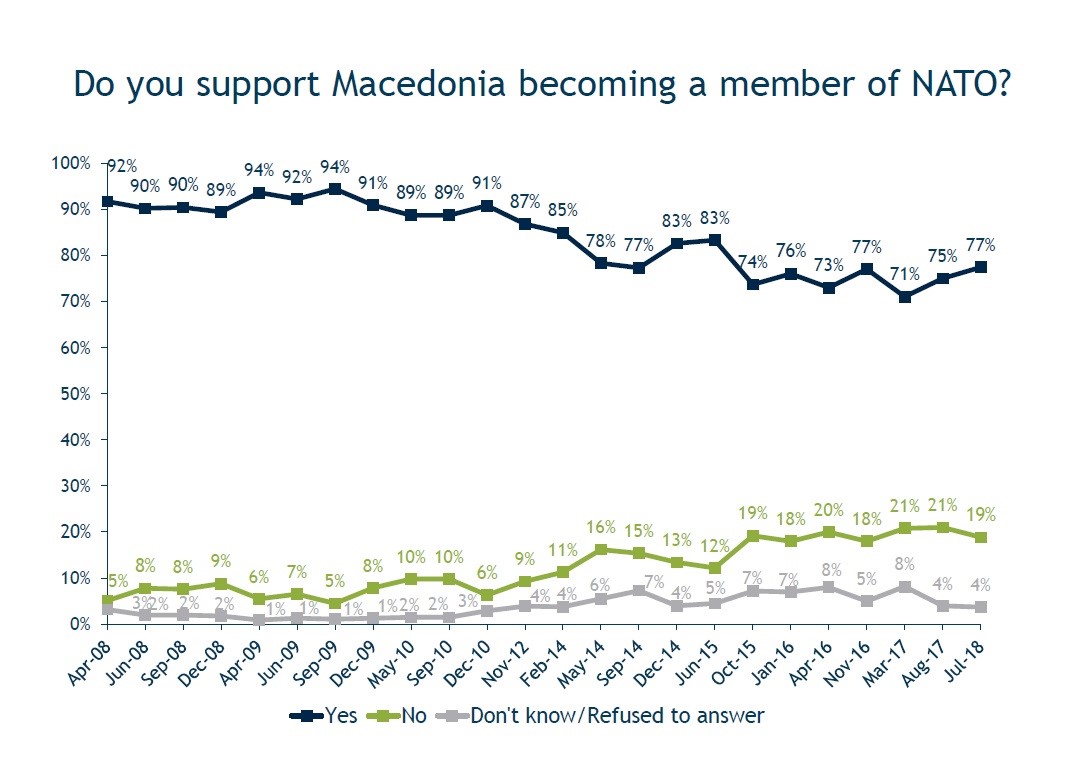

EU and NATO accession have been Macedonia’s strategic objectives since its independence, and they continue to enjoy high support among citizens. According to IRI polling, 83 percent support EU accession and 77 percent support NATO accession. Citizens see integration into the EU as the only way to improve the performance and behavior of the government institutions and politicians who are not trusted by citizens. Macedonians see EU accession as a means toward gaining a decent standard of living and strong trustful institutions.

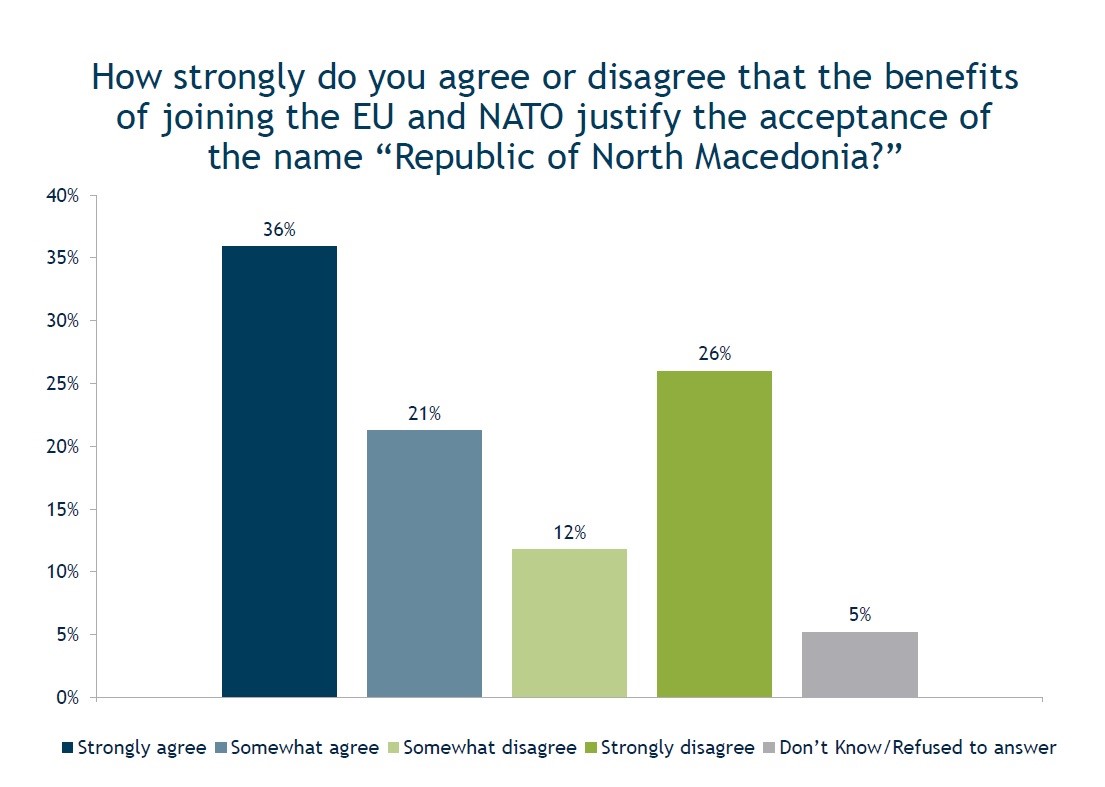

But to trade one’s name for this goal is a high price to pay. The opposition states that such a trade-off is unacceptable and it is a capitulation to Greece. Instead, they claim a better deal can be reached, and the name can be preserved. The trade-off is also inconceivable to many Macedonians. IRI’s July 2018 poll found that one third (38 percent) somewhat or strongly disagree that joining the EU and NATO justify acceptance of the name “Republic of North Macedonia.”

A name bears one’s identity and Macedonians feared changing the name would take away their identity. In the referendum on joining the EU and NATO by accepting the Prespa agreement, only 36.89 percent of the citizens came out to vote, though those who did overwhelmingly supported it (91.46 percent). The opposition led a silent boycott campaign in order to suppress overall turnout and invalidate the referendum.

The acceptance of “North Macedonia” has fundamentally divided ethnic Macedonians, deepening the already existing political polarization. On one side are those who see this as a price worth paying to join the EU and NATO, and on the other are those who are extremely angry about changing the name.

It won’t come naturally for Macedonians to add “North” when referring to their country. The change of their country’s name was a large sacrifice, constitutionally, legislatively and, even more so, emotionally. All Macedonian prime ministers knew such act would be perceived as treason by many Macedonians and none of them were prepared to take that step for 27 years.

Now It’s Everyone’s Turn to Deliver

Now that the bitter pill has been swallowed and Greece has ratified the Prespa Agreement, the name issue can no longer be blamed for Macedonia’s lack of progress. There is a lot of homework to be done to improve governance and meet rigorous EU accession criteria. Elected and appointed officials must follow the law and democratic principles. Responsibility for democracy and rule of law lies within the country’s political elites; they cannot lay the blame on Greece for blocking Macedonia’s path forward anymore.

It means that the name issue is no longer an excuse for the EU as well. Macedonia has resolved its bilateral issues, first with Bulgaria and now with Greece. It demonstrated the ability to resolve its own problems independently. The EU has left Macedonia in the waiting lounge for too long. Macedonia delivered a big political sacrifice and became a rare example of Balkan success story.

A future without EU and NATO paints a grim picture for the country. It will signal to politicians that they need not worry about upholding democratic values and standards that Euro-Atlantic integration requires. Distancing from the West will create a vacuumed, making Macedonia more and more vulnerable to Kremlin influence. Another cycle of democratic backsliding will further discourage citizens and increase the waves of emigration toward the European Union countries.

It is time for the EU and its member states to deliver and set a date for the start of accession negotiations. Such an act would send a clear message to the progressive, pro-European elites in the country and region that passing big compromises and closing existing disputes pays off and is worth the risk.

Top