The Catatumbo, a region in Colombia’s northeastern border with Venezuela, has long been at the heart of the country’s violent conflict due its strategic location for drug trafficking and other illegal activities—and its historically limited state presence. According to DEA in 2016, 92 percent of the narcotics seized in the United States was of Colombian origin, and Catatumbo is currently the third region in Colombia leading coca production.

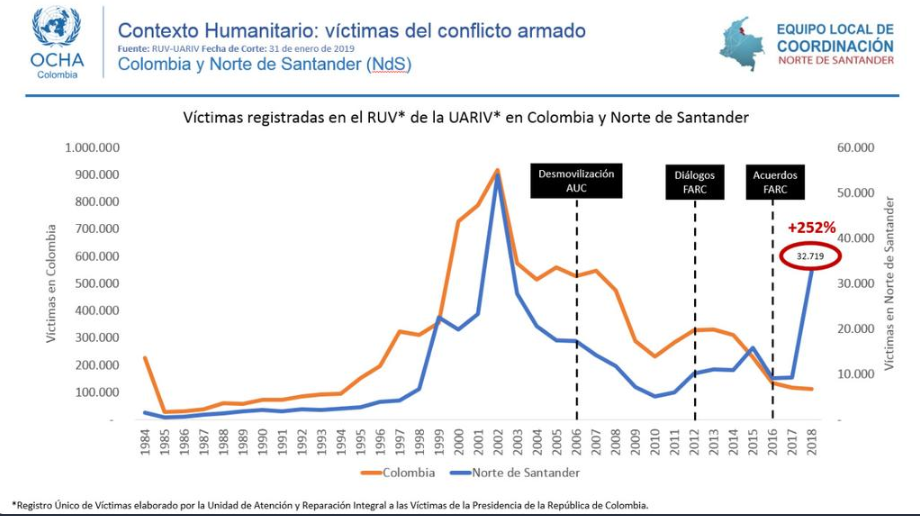

As such, the region has not seen a substantial reduction in violence since the signing of the Peace Accords in 2016. While nationwide, the rate of homicide has fallen, the armed conflict is more alive than ever in the Catatumbo. To make matters worse, the region is now feeling the effects of Venezuelan migration, which burdens the already scarce state resources.

Under a current project funded by the National Endowment for Democracy, IRI is supporting a project of the Peace Committee in Colombia’s House of Representatives, Del Capitolio al Territorio (from the Capitol to the Territory). The objective of this project is to visit post-conflict zones, oversee the implementation of the Peace Accords and to understand the needs of the regions.

On March 14 and 15, IRI supported the field visit of a multiparty group to the department of Norte de Santander, where the Catatumbo is located. We met with local and state governments, social leaders, agencies responsible for the implementation of the Agreement, international organizations and women’s and victim’s organizations.

We learned that to achieve a true peace, the Catatumbo needs an integral presence of the Colombian state, beyond the presence of military forces. Two factors are complicating the implementation of the peace in the Catatumbo: continued armed conflict and migratory flows from Venezuela. Since the signing of the Peace Accords, there has been a reconfiguration of the conflict, since following the demobilization of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), and their withdrawal from the territory they controlled, different armed organizations are fighting over the control of coca crops in Catatumbo. This has caused an increase in disputes between other armed groups, including the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), dissident members of the FARC who refused to lay down arms and criminal gangs for the territories once controlled by the FARC.

At the same time, beyond military forces, the State still has very little presence in the region. This means that the development of this region depends on measurable efforts in areas such as improvement of the local justice system, transportation infrastructure and access to electricity and gas. Throughout our meetings with the groups mentioned above, they all agreed on the need for the government to develop a coherent strategy for the Catatumbo that includes crop substitution and the continued incorporation of families into the government’s national program for illicit crop substitution. Actions limited only to aerial fumigation would not do enough to decrease the level of violence in the region.

The surge in Venezuelan migration adds to the region’s challenges. An estimated 25,000 Venezuelans live in Catatumbo, and more pass through it to get to other regions in Colombia. These migrants are exposed to violence and insecurity as illegal armed groups take advantage of their vulnerability. They also suffer from discrimination, poor living conditions and labor exploitation as some 8,000 of them are pressed into cultivating coca.

However, despite its problems, Catatumbo is also a region rich in opportunities: its rich lands boast abundant rice crops, fish farms and palm plantations, oil and charcoal, and the potential to produce wind energy. But its most valuable resource is the resilience of its people who want to work for the development of their region and know how to do it. These people demand the attention of the authorities to build a future together.

Top