As the primary nomination process for Kenya’s August 2017 general elections heats up, the potential for election-related violence are at the forefront of news coverage and citizen concerns.

These concerns are a reflection of the vivid memory of violence during the 2007 election cycle, which, according to Human Rights Watch left up to half a million people displaced, over 1,000 dead and created instability by exacerbating ethnic divisions in the country. As a result, economic growth in Kenya dropped from 7.1% in 2007 to 2.5% in 2008. Today, it is estimated that 50,000 people are still displaced as a result of this crisis. Instability and economic decline in Kenya affects the entire East Africa region, and could increase regional insecurity, disrupt trade routes and negatively impact some of Africa’s most volatile countries such as Sudan and Somalia.

For Kenyan citizens, violence in this election cycle is inevitable. Recent IRI stakeholder interviews revealed that in the recently completed voter registration process it was apparent that many people, particularly women and youth, would rather remove themselves from the election process than take the chance of being involved in violent conflict. It is concerning that voters in general, and specifically women and youth, feel marginalized from the electoral process due to the threat of violence.

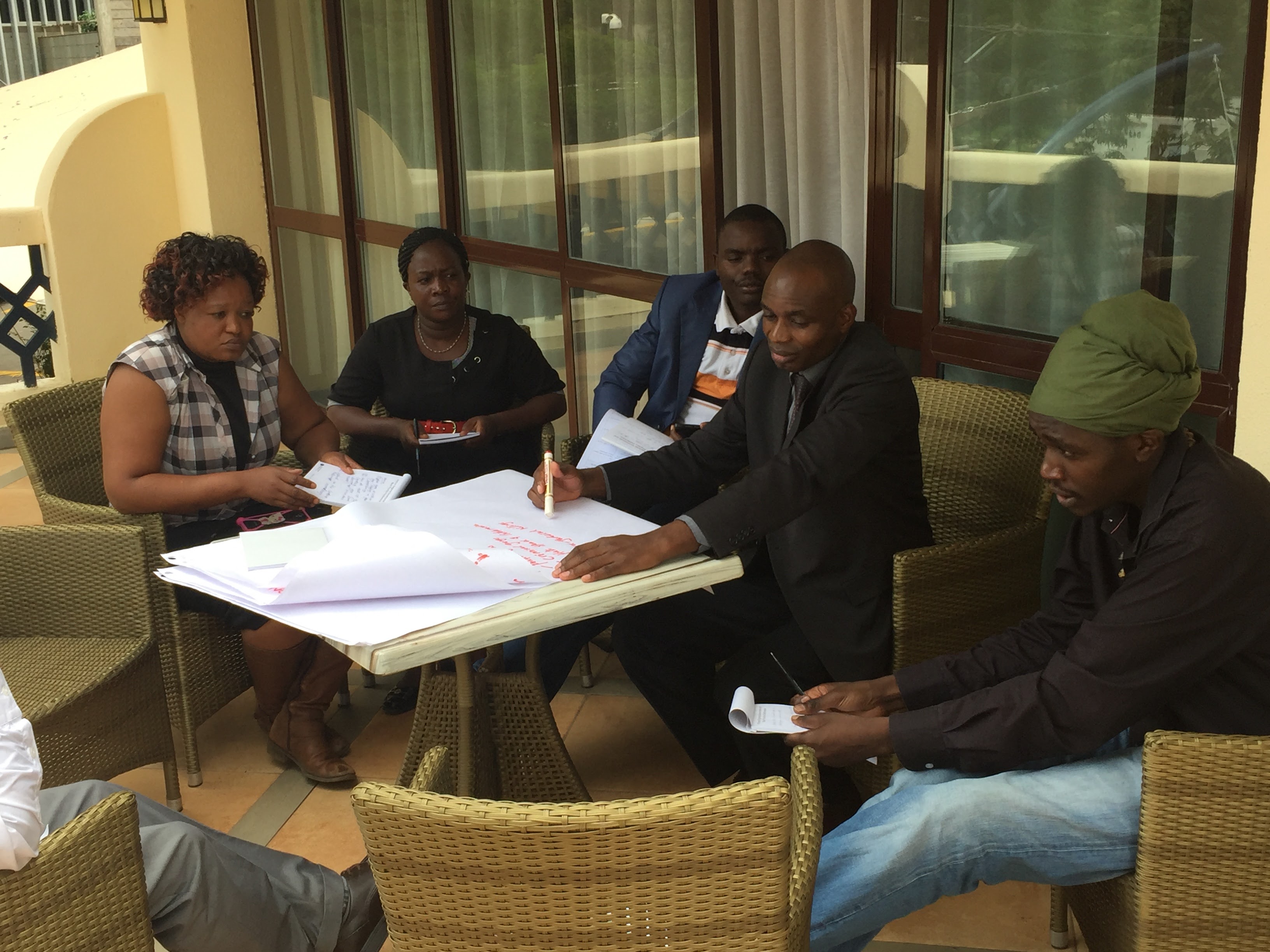

Last month, the International Republican Institute convened a diverse group of stakeholders to discuss the elections and assess the potential for conflict in this election cycle; state institutions, civil society, and citizens were all present. The Nairobi-based participants see their city as a potential epicenter for violence, which served as the primary motivator for of participants to engage in peacebuilding activities within their communities.

“As a Peace Member, my expectations are to see how we can come together to make peace for this election. We need to be an example in the areas where we are, as ethnic groups, we are not one class, but we want to be one.” – Cohesion Champion, Kibera

In speaking with several participants, it was clear that almost everyone in attendance had experience with violence in the past either as perpetrators or victims. One participant from Mathare explained that he had been the leader of a gang that was violent during the 2007/8 elections. A quiet 35-year-old, with sincere eyes and a quirky sense of humor, he opened up to me about his experience. Out of 20 young men in his gang, there were only two left alive when the violence subsided. He explained that he was directly affected by the violence as his fiancé who was three months pregnant was killed in a retaliatory attack. Recognizing how senseless this violence was, he now acts as a Cohesion Champion in Mathare. Because he still knows many people who are in gangs, he can connect with them to deter them from violence and promote peace and accountability in his community.

Another participant from the Ministry of the Interior, a particularly bright woman in her late thirties, Ruth explained that her decision to work in peacebuilding was deliberate. She is originally from Kericho, where her family’s home was burned during election related violence in 1992, after which they lived as internally displaced people (IDP) in a church for two years. She eventually went to school and obtained an MA in Conflict Management and now works as the Cluster Peace and Cohesion Coordinator covering three counties including Nairobi County. She told me that with the elections coming up the main thing that Nairobi needs is to sensitize youth on the drivers of violence.

“Youth are vulnerable now…because there is high unemployment and they are idle. No one is engaging with them and they lack a connection to do the right thing; they feel hopeless to improve their situations through peaceful means.”

The vulnerability of youth was an issue that came up several times during the two-day workshop, particularly as it related to the threat of violence during the elections. Other issues discussed at length included inequality manifested through tribalism or ethnicity. Political intolerance, hate speech, and cyber bullying were also discussed, particularly through the lens of lack of information or misinformation in the media. There were in-depth discussions about the contrast between freedom of speech and preventing hate speech and how this applies to the media and their role in maintaining peace. Corruption was a main topic, as so deeply rooted in Kenya’s political system that it has created an expectation that “handouts are the best way to go,” which in turn fuels political loyalty and willingness to perpetuate violence. This spiraled into the role of state institutions with a mandate to ensure peace and their effectiveness in doing so. The NCIC presented on their role as well as their limitations, and explained that they are working to improve legislation so that they can better work with the justice system to ensure that violators are tried in a timely and just manner.

Through the workshop, participants identified the core cause for conflict related to election violence in Nairobi as access to political power and resources. Other causes that were discussed included: credibility of the electoral process, unequal political representation, ethnicity, bad governance and uneven distribution of resources. Bad governance as an overarching cause of the other issues was discussed and agreed upon, however in the context of electoral violence, the group agreed that access to political power and resources was more relevant as the core cause of electoral violence specifically in Nairobi. This workshop allowed for the facilitation of a meaningful discussion on these issues between youth and state institutions, but it also equipped participants with the knowledge of how to objectively breakdown the elements of the conflict in order to effectively develop community interventions to prevent and manage conflict that may result in violence during the election cycle.

“You are here now as learners, but when you go out, you should be champions, to emphasize stopping the conflict, and not just handling the conflict.” –Deputy County Commissioner, Nairobi County

Motivated by their memory of violence in the past, participants were deeply engaged with one another in dialogue to develop community interventions to promote peace and mitigate violence. These are resilient actors, eager to rise above existing power structures and ethnic divides to ensure a peace. As the Kenyan elections progress, IRI will continue to equip citizens and institutions at all levels with tools to maintain integrity and fairness, so that the most vulnerable actors can actively participate in their democratic roles without fear of violence.

Top