The poisoning of former Russian intelligence officer Sergei Skripal and his daughter in Salisbury, United Kingdom, on March 4 has been covered quite extensively in the Czech media.

Approximately 900 articles mentioning Skripal were published from March 4-19 and monitored by our team at the Prague Security Studies Institute (PSSI) using the IRI Beacon Project’s >versus< media-monitoring tool. This extensive coverage was driven not only by the serious implications of the case themselves, but also by allegations that the Czech Republic was directly involved in it. While Czech experts helped the British to examine the nerve agent used in the Skripal poisoning, the Russian government suggested that the Czech Republic could be the country from which the substance originated–an allegation which was denied by Czech authorities.

The coverage of the case in the mainstream media was quite uniform, since most reports drew information from the Czech News Agency. Many of the articles focused on the actual course of events and, from the beginning, pointed to the over-whelming evidence showing Russia as the perpetrator. Even tabloids covered this issue quite extensively and, although they at first focused on the case more informally – such as showing holiday photographs of the Russian ex-agent Anna Chapman (who was swapped for Skripal in 2010) who at the time posted bikini photos from her luxurious vacation in Thailand – they later changed tone and reporting became more serious about occurring events.

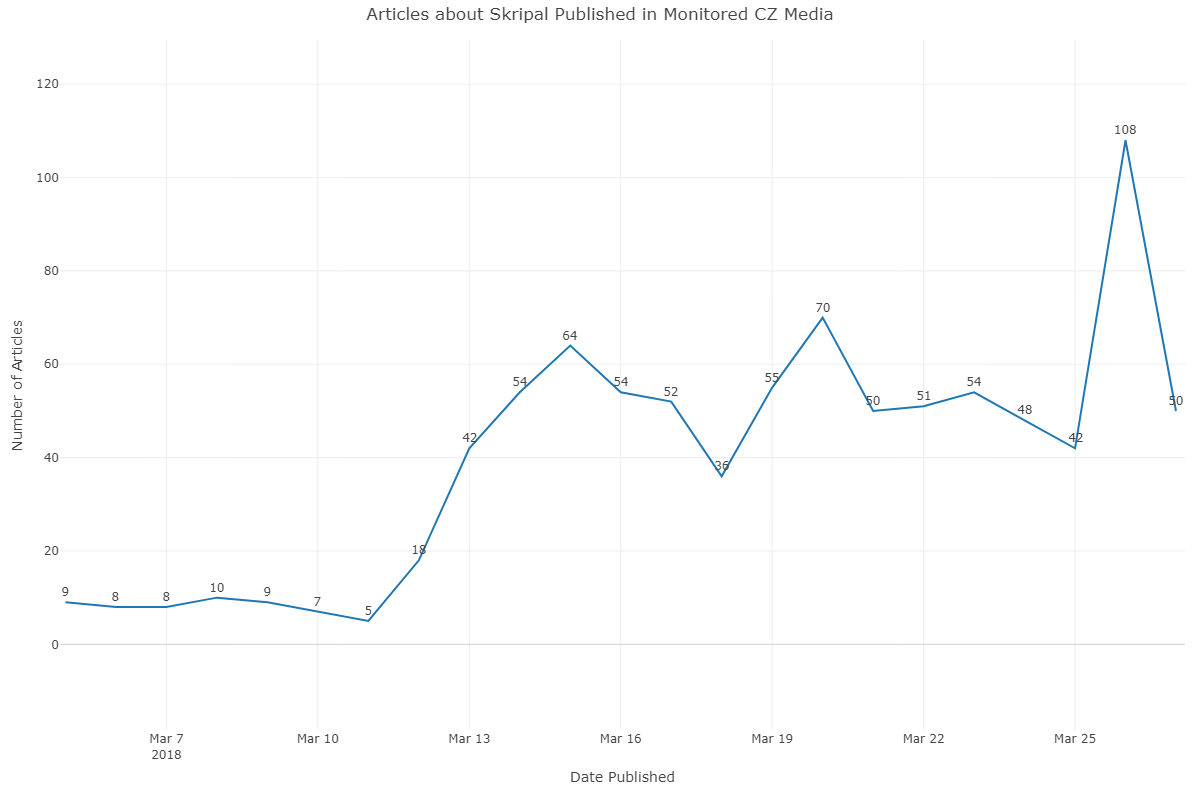

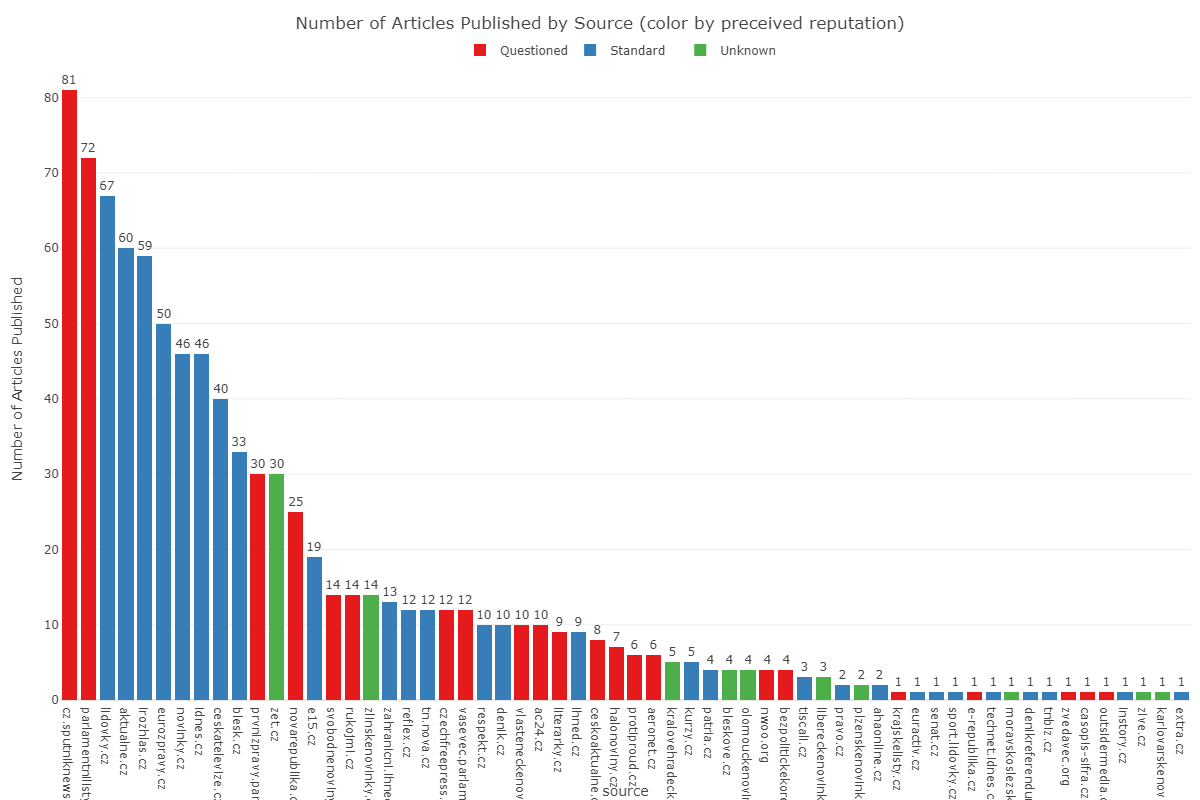

By contrast, the Czech alternative media scene, consisting of around 40 websites with strongly tendentious commentaries spreading conspiracy theories or disinformation, focused on the ‘backstage’ of the event. Although the case was largely ignored in the days immediately following the poisoning, PSSI saw significantly increased activity from March 12 onward, when the Czech version of Sputnik quoted the official statement of Putin.

The first conspiracy theory appeared on March 13, when conspiracy theory outlet Zvědavec published an article presenting the Skripal case as part of a British campaign against Russia and mentioning the existence of a secret laboratory close to Salisbury. This allegation in turn first appeared in Sputnik, was then copied by the well-known conspiracy theory outlet Information Clearing House, and consequently translated into Czech, providing an excellent example of the way disinformation and conspiracy theories spread across online outlets. Further, that same day, Lubomír Man, another well-known contributor to the Czech alternative media scene (and one who played a significant role in shaping the narrative about Skripal throughout the period monitored), published in VašeVěc a commentary in which he argued that Russia did not have any motive to murder Skripal. On the same day, his thoughts were shared by seven websites spreading disinformation. Man further contributed to the debate by translating two articles written by American writer Paul C. Roberts, who mentioned Skripal in the context of impending nuclear confrontation between Russian and West, which he argued is desired by the American ‘neoconservative elite.’ Both articles by Roberts, who is often quoted in Czech alternative media, have spread quite extensively.

Another important development was an initial reference on March 14 to a New York Times article from 1999 that allegedly proved that America had access to the nerve agent with which Skripal was poisoned. This narrative was brought into the Czech media space by Russian media – Sputnik CZ and the RusVesna news agency. This information was taken up by other websites, some of which openly blamed the US for the assassination attempt. The intensification of the conspiracy theories continued on Thursday, March 15, when the Pro-Kremlin activist Jiří Vyvadil suggested that the poisoning of Skripal was conducted by Russian oligarchs living in Britain in order to discredit Vladimir Putin before the “elections.” Association of Independent Media Chairman, Stanislav Novotný, questioned Russian involvement, and linked the Skripal case with up-coming anti-government protests in Slovakia by suggesting that both events were part of a wider conspiracy orchestrated in order to start a conflict.

The above-mentioned theories are a small sample of those spreading in the Czech fake news space. This also highlights the alternative media’s connections with Russian outlets such as Sputnik. Our media monitoring has shown the intensity at which fake news can travel and confuse the readership by providing multiple (often contradictory) theories to drown out the overwhelming evidence. Even more seriously, that such stories are legitimized by public figures (such as former diplomat Jaroslav Bašta on the website První zprávy or political scientist Zdeněk Zbořil on Parlamentní listy), further highlights a worrying trend of ‘normalizing’ conspiracy theories in every-day Czech politics, and creating additional space for distrust and discord, on which home-grown populism and hostile external actors feed.

Top