“This is Our Independence Day”: Voters in the United Kingdom Decide to Leave the European Union

Very few people saw this day coming when David Cameron began making promises to the Eurosceptic part of his party as part of his campaign for the Conservative leadership in 2005.

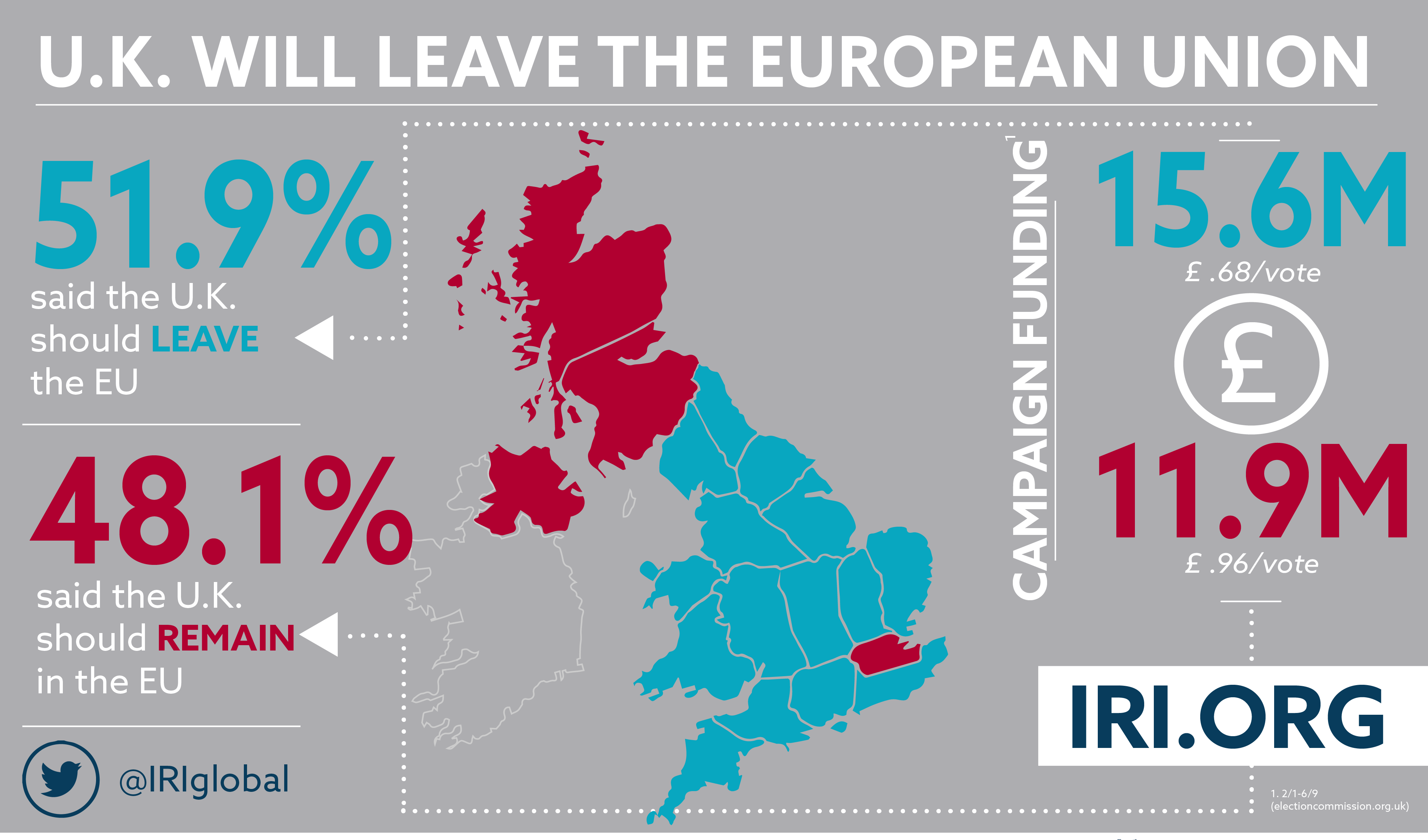

But now the results of yesterday’s referendum on the United Kingdom’s membership in the European Union (EU) are in, and they’re remarkably clear: with turnout at 71.5 percent (the highest for a national vote in the UK since 1997, and with over a million more people registered this time), the people of the United Kingdom voted 51.9 percent to 48.1 percent to sever the country’s current relationship with the EU and take it into uncharted economic and political territory over the next several years. Cameron announced his resignation early this morning.

Although United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) leader Nigel Farage had tweeted what seemed like a concession for the “leave” side very early in the evening (followed a bit later by an “unconcession”), the “remain” campaign ultimately conceded defeat at approximately 5:00 am London time. Having months ago already lost the battle to frame the debate and the campaign to the “leave” side, “remain” campaigners – including the prime minister himself – were never able to find a way to make a solid positive argument for staying in the Union, particularly once “leave” was able to tie the question of immigration and migration to the question of staying in.

What began, therefore, as an internal struggle for the heart and soul of the Conservative Party (a large part of the voter and membership base of which has long been critical of the EU) turned into both a referendum on the real issue – EU membership – and on the performance of the establishment political parties and the London elite. In a pattern we have seen repeated all across Europe in recent elections, voters were out to send a message to the capital that business-as-usual was no longer to be tolerated and that the advice of elites was to be shunned, as wide swaths of the historic industrial north of England went to “leave” by significant margins.

Traditional Tory Eurosceptic voters combined with disaffected Labour ones to yield a throw-the-bums out message that came across much more clearly yesterday in the referendum format than it ever could in a first-past-the-post general election. In these areas, the leadership of Labour should be very worried for the future, as UKIP says it intends to do to Labour in England what the Scottish National Party (SNP) has already done to it in Scotland – make it a consistent outsider in place where it once had a stronghold.

In Scotland itself, where many suggest that a new independence referendum movement could be the result of the “leave” decision, the “remain” side won handily, but turnout was not strong enough to significantly improve the “remain” performance in the UK as a whole. In fact, even though literally every one of the reporting areas across Scotland voted “remain” in large margins, turnout in Glasgow was only 56.2 percent, well under the national average. There will surely be pressure now by the Scottish National Party to move toward a new referendum or toward some sort of special relationship with the EU even in a situation in which the UK, as such, leaves. More uncertainty is definitely in the cards.

In Wales, support for “leave” was surprisingly strong, particularly since many expected a performance at least somewhat closer to that of Scotland. But the increasingly evident weakness of Labour in the country and the growing attraction of UKIP as a party here dropped the bottom out from under the “remain” campaign. “Remain” won only three of the Welsh counting areas and lost Swansea, the country’s second city. In Northern Ireland, where the vote broke down along Unionist and nationalist lines, “remain” won in all counting areas, giving it an overall win of 55.8 to 44.2 percent.

Interestingly, it might be in Ireland where the most tangible and visible impact of a decision by the UK to leave the EU will be felt, as the boundary between the Republic of Ireland, which is in the EU, and Northern Ireland, may once again take on the character of an international border. Will customs inspections be introduced? Will passports be checked? No one is quite sure. Sinn Fein has already called for a referendum on Northern Ireland’s independence from the UK.

How the process of leaving the Union works is also unclear. In theory, Cameron could notify the European Council as soon as next week that the UK intends to begin the process of leaving under Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, a process which will likely take years. Or he could appoint a person or a team to study options on how to move forward, lay out that course to the public, and then begin to implement it. In any case, Westminster will have a huge legislative workload on its hands as the process moves on, since it will have to pass legislation to replace EU-level laws now in force.

And on the EU side, there will also have to be a number of changes. There will be no more seats for British MEPs of any political persuasion in the European Parliament, no more positions for the thousands of British citizens in the various institutions of the EU bureaucracy, and no more room for Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat, Green or even UKIP membership in the various party-family institutions of the EU. Just for example, it is very difficult to see how the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists (AECR) group and its related institutions will survive in any viable form with its most important component party – the British Conservative Party – absent.

Germany will now fully dominate the Union in a way that even Berlin concedes is not healthy. No other EU country comes close to it in terms of population or economic power. The smaller new-member states of the EU in Central and Eastern Europe will feel even more abandoned by the “West” than they do today and this will give rise to a need to outline new alliances to protect stability in the region.

The victory for “leave” in the UK will now also give impetus to the full range of more and less extremist parties on the continent that have built their reputations on recovering national sovereignty, and we can expect to see growing calls for similar referenda in, at least, France and The Netherlands, and likely elsewhere. It is more than clear that the economic uncertainty caused by the “leave” vote (the pound lost at least 10 percent of its value against the dollar in just a few hours, and the FTSE 100 tumbled 500 points) will hamper efforts to get Europe’s lackluster economic growth back on track for several years. But these are all problems for the future.

In a case of life imitating art (or at least film) Nigel Farage said triumphantly that “23 June will go down as our independence day.” There’s no doubt that the British people have voted to leave. But the referendum designed to resolve the question of the UK’s membership in the EU has now opened far more questions than it has answered. If cooler heads prevail on both sides of the English Channel, solutions can be found that will keep the transatlantic community healthy, vibrant and working together.

Top