The International Republican Institute’s (IRI) public opinion surveying is a cornerstone of our mission to advance democracy worldwide. Since 1998, IRI has polled more than 1.5 million citizens with more than 1,000 polls in over 100 countries, including in some of the world’s most challenging environments. We believe that the availability of reliable and accurate information about a public’s needs and preferences is essential for functioning democracies. This information allows governments and citizens to interact constructively to address problems requiring political solutions.

Because this information is so critical to IRI’s mission, the Center for Insights in Survey Research (CISR) is specially tasked with ensuring the reliability and accuracy of the public opinion data that IRI collects. In addition to leveraging the expertise of our regional specialists and in-country survey research partners, and refining our data collection methodologies and questionnaires prior to data collection, a robust data quality control (QC) regimen is one of the primary ways that CISR ensures the reliability and accuracy of IRI’s polling data. This QC regimen checks for a wide range of potential issues including problems with sample representativeness, data structure and data entry errors, and other unusual response patterns which might indicate problems with specific survey questions, interviews, or interviewers.

Quality Control During Fieldwork

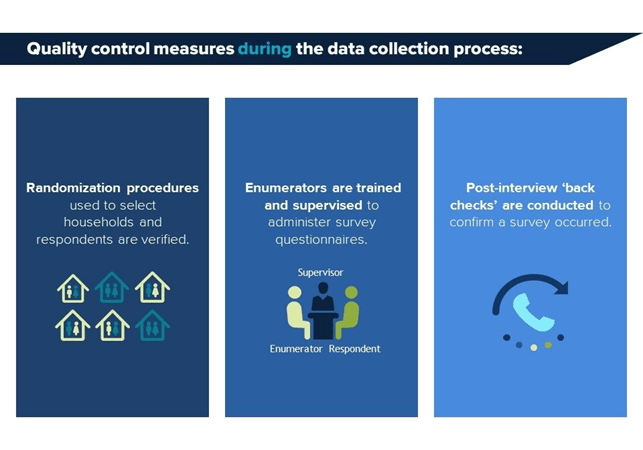

After a survey’s sampling methodology and questionnaire have been finalized, IRI’s in-country survey research partners typically carry out the first series of data quality control measures during the actual data collection process, as well as immediately after data collection. As surveys are being conducted, our survey research partners typically supervise an agreed-upon percentage of interviews. In the case of face-to-face surveys, interviewers are usually supervised as they carry out the randomization procedures that are used to select households and respondents. Interviewers are also supervised to make sure that they are administering the survey questionnaires correctly. In some instances, parts or all of the interviews are audio recorded. In addition, our fieldwork partners typically carry out an agreed upon percentage of “back checks,” meaning that the respondents who were previously interviewed are re-contacted to verify that an interview took place. This includes readministering several of the survey questions and ensuring that respondents’ answers are consistent with the originally collected responses. Our partners also typically carry out an initial review of the sample’s representativeness and verify that data has been accurately recorded into a survey dataset.

Post-Fieldwork Quality Control

After receiving a survey dataset, CISR carries out an additional review of the survey data and paradata, as well as other performance metrics from fieldwork. The first stage of this review is foundational. CISR verifies that the sample is representative of the country or other population being studied. This entails comparing our sample’s demographic profile to both official statistics and samples from previous studies that IRI has done on the same population. Where we lack recent CISR polling data, we may draw upon third-party surveys, especially those based on large nationally representative samples. CISR also reviews other fieldwork performance metrics such as response rates, the time it took to conduct interviews, the workload of individual interviewers over the data collection period, and the locations of specific interviews that were conducted. For example, an interviewer who has notably low “interim times,” meaning the time elapsed between two interviews, may not have adhered to the complex household and respondent selection protocols, and all interviews conducted by this interviewer would be flagged for additional checks. At this stage, CISR also reviews the dataset to ensure that data has been recorded correctly, including data for more complex types of questions such as filtered or multiple-response questions. If the sample appears representative and the survey data appears to have been organized correctly, CISR then starts to apply a series of more sophisticated data quality checks.

This second phase of CISR’s data review process analyzes patterns of responses to different survey questions. CISR conducts this “response analysis” at several different levels:

- First, and most fundamental, is the interview level. These are responses made by individuals who were surveyed.

- Second is the enumerator level. These are responses that were collected by interviewers (enumerators), who would have conducted interviews of multiple individuals.

- In the case of face-to-face surveys, CISR also often conducts a review at the sampling point level. At this level, groups of interviews that were conducted in the same small geographical locations are analyzed. In IRI’s nationally representative face-to-face studies, sampling points usually consist of clusters of between 5 and 10 interviews. Often two enumerators are assigned to collect data at each sampling point. So, a review at the sampling point level means analyzing responses in terms of these groups of 5-10 interviews which were conducted by 2 enumerators.

These checks are conducted at multiple levels to check for isolated and systemic quality issues at the interview, enumerator, and sampling point level. Interview-level checks might reveal problems with specific interviews. Meanwhile, enumerator and sampling point level checks might reveal broader problems with data collected by specific enumerators, or data collected in specific locations. Issues identified at any level will trigger additional data checks.

Types of Response Analysis

CISR conducts many different checks at the response analysis phase of the review. These checks may include checks of interview similarity, non-attitudes, flatlining, a review of sensitive questions, and internal cohesion.

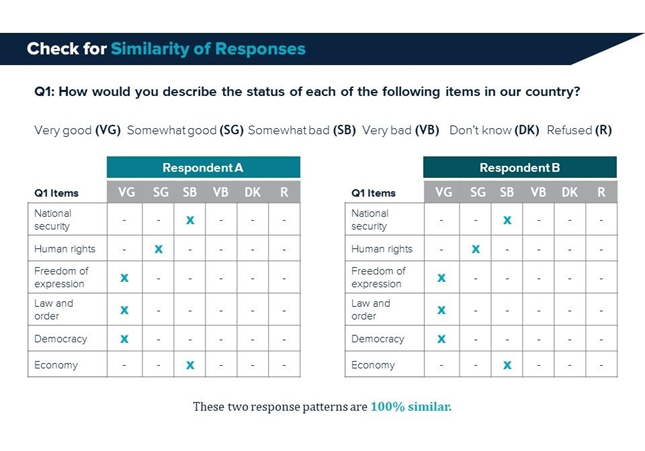

Similarity: CISR checks for interviews that are 100% similar, as these are typically duplicates that were introduced via a data entry error made by IRI’s fieldwork partners. IRI also checks interview similarity at several lower thresholds since this might indicate broader problems with specific enumerators. For instance, if an enumerator tended to record interviews which were all 98% similar to each other, this might indicate that the enumerator recorded false data – or that there was some other problem with an enumerator’s ability to carry out interviews and enter data correctly.

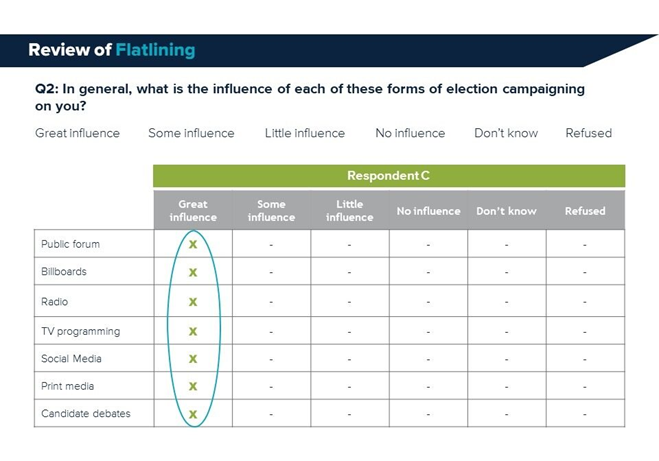

Flatlining: Flatlining (i.e. straightlining) can occur on battery questions that were asked using a consistent set of response options. For example, a multiple-response battery might ask whether different forms of election campaigning influenced respondents ahead of an election. Flatlining occurs when a respondent makes the same response to all of the different forms of campaigning that they rated (e.g. Great influence to all 7). Flatlining may indicate that respondents were not paying close attention to a battery question, or it may indicate that they were frustrated by an overly long survey and rushed through the battery by naming the same response to each question. Similarly, flatlining at the enumerator level might indicate that a particular interviewer did not record data accurately.

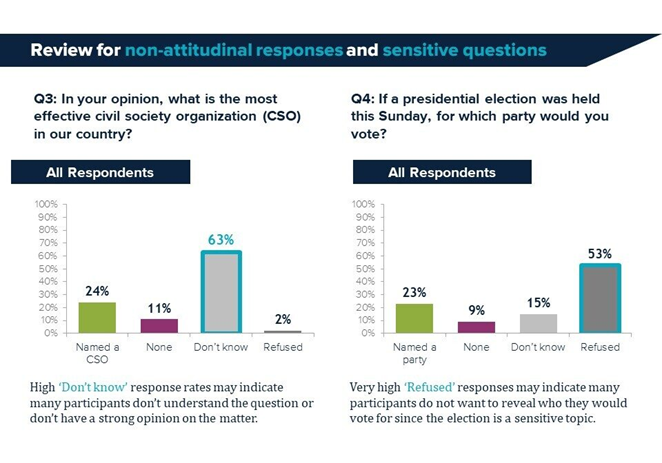

Non-attitudes: Non-attitudes include “Don’t know” and “Refused to answer” responses to survey questions. High rates of non-attitude responses to a specific survey question might indicate that the question was poorly understood by respondents, or it may indicate that the question was sensitive and respondents felt uncomfortable reporting their actual attitude. Like the similarity check, high rates of non-attitudes reported by particular enumerators can indicate a problem with a specific interviewer’s ability to administer the survey questionnaire and record data accurately. And, higher rates of non-attitudes in particular sampling points might indicate that respondents were less able to comprehend the survey in certain geographical locations, or that some questions were more sensitive in particular areas of a country.

Sensitive questions: In most places, questions about certain political views (including who respondents would vote for in a hypothetical election) are difficult to ask and respondents might not always be willing to give their honest opinion. Likewise, enumerators might be inclined not to administer difficult-to-ask sensitive questions correctly; or, at worst, may fabricate data to reflect their own political preference on a controversial matter. Either way, CISR pays special attention to data from sensitive questions and looks for unusual response patterns that might indicate a problem with these kinds of survey questions.

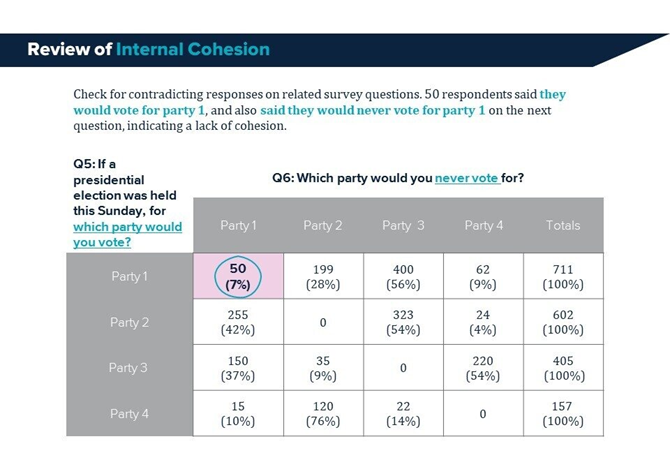

Internal cohesion: Internal cohesion refers to the consistency of respondents’ answers on related survey questions. For example, one survey question might ask respondents about which party they would vote for in a hypothetical election. Another survey question might then ask respondents which party they would never vote for. In most cases, we would expect there to be a high degree of cohesion between these two responses; meaning that those who plan on voting for a particular party would not name the same party as one that they would never vote for. Conversely, if respondents did name the same party as one that they would vote for as well as one that they would never vote for, this would seem contradictory and would probably indicate a lack of cohesion. Such a contradictory response pattern could be the result of data entry error, or it could also be the result of respondents misunderstanding one of the two questions in this example.

These examples of data checks conducted by CISR are not all-encompassing, and they also do not take place in any rigid order. However, they are all designed to look for systemic irregularities in the data which might indicate problems for the reliability and accuracy of IRI’s survey data. If CISR’s review detects problems on any of these checks, these are typically resolved with the assistance of our in-country survey research partners. Data entry errors can often be corrected. When errors cannot be corrected, or when there are more systemic problems with specific interviews, enumerators, or questions, this might require specific cases or specific questions to be removed from the dataset entirely.

In addition to applying this robust quality control regimen to specific surveys, CISR’s quality control approach is also longitudinal: we apply these checks across multiple surveys and track quality control metrics over time. This post-fieldwork quality control regimen supplements IRI’s other pre-fieldwork measures (such as questionnaire pretesting) to ensure the high standard of quality that IRI demands of its research products.

Top