- Introduction

- Main Findings

- Executive Summary

- Europe’s Path Back from the Fringe

- Different Drivers

- Methods

- Parties and Elections

- Demographic Profile

- Fringe Attitudes

- Immigrants and Liberal Values

- Swing Voters

- Addressing Immigration

- Coronavirus Context

- Conclusion

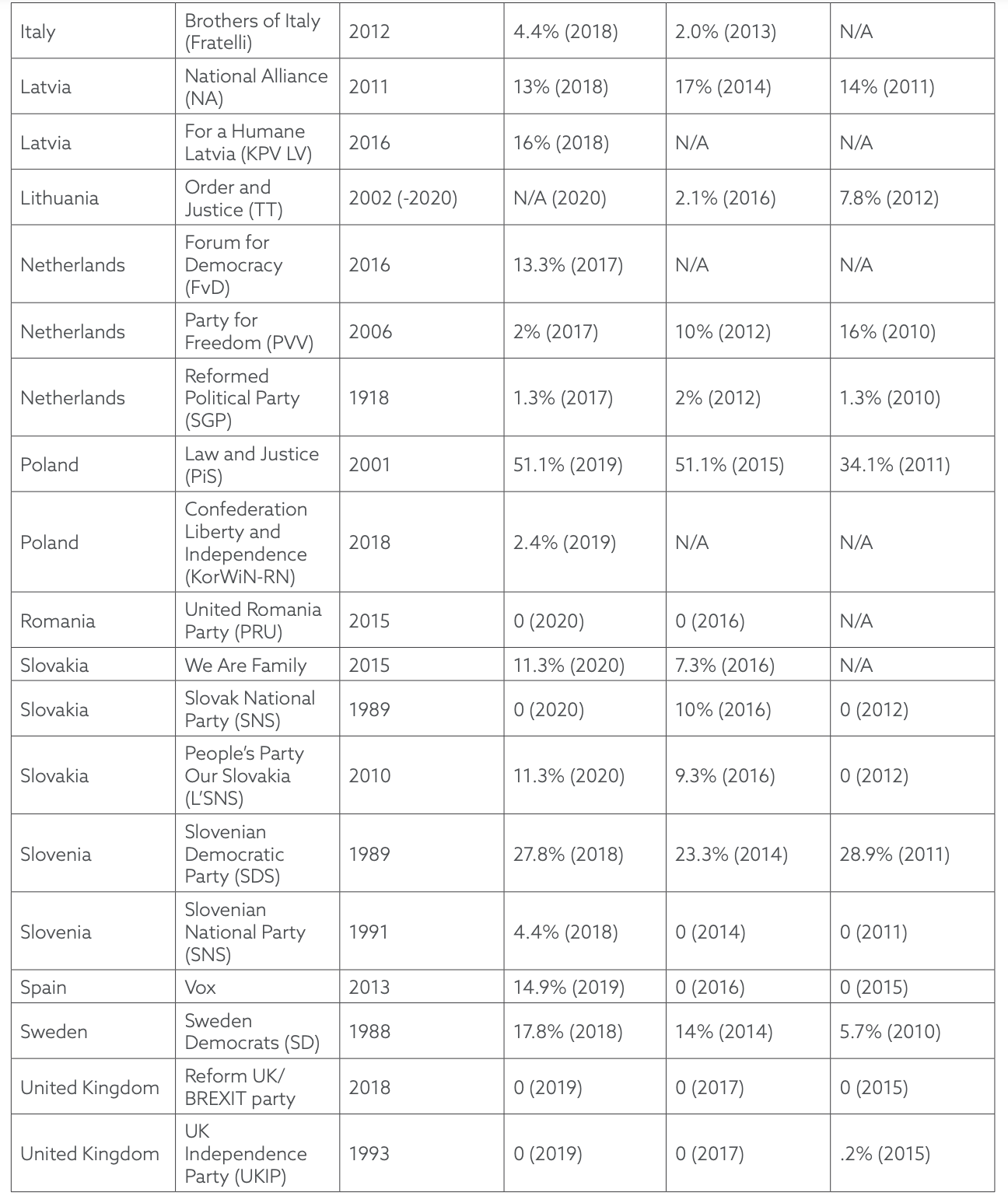

- Appendix A: Recent Election Results and Electoral Preferences

- Appendix B: Methods

- Appendix C: Additional Results

- Endnotes

Introduction

WASHINGTON, DC: The International Republican Institute (IRI), with its partners the Alliance of Liberal Democrats for Europe (ALDE) and the European Liberal Forum (ELF) is releasing the findings of a cooperative effort commissioned to study the triggers to fringe party voting in Europe, authored by George Mason University Associate Professor of Policy and Government, Justin Gest, with Jeremy Ferwerda, Assistant Professor of Government, Dartmouth College, and Tyler Reny, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Claremont Graduate University.

In this publication, entitled Europe’s Path Back from The Fringe, Gest and his colleagues provide an anlysis of the survey’s results, studying the demographical and psychological drivers of fringe party support in 19 countries throughout Europe (Germany, France, Italy, the UK, Spain, Poland, Romania, Netherlands, Czech Republic, Sweden, Hungary, Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, Slovakia, Lithuania, Slovenia, Latvia, Estonia) between August and September of 2020.

Results notably show that fringe party voting should not be understood as a uniquely right-wing or left-wing phenomenon, as both fringe party supporters are united by common illiberal attitudes, although these vary between the two groups. The study also shows that fringe parties have mild to moderate room from growth.

With its innovative methodology and an analysis that separates fact from fiction, Europe’s Path Back from The Fringe is set to become an indispensable tool to study the recent phenomena of political disruption across Europe, which IRI is studying in-depth with political parties. Survey results will be shared widely among the Institute’s partners on the continent.

Main Findings

• Illiberal attitudes unite both far-left and far-right European fringe party supporters.

• Far-right support is correlated with high ethnocentrism, inflated estimates of demographic change, and distrust of public institutions.

• Attitudinal factors explain party preferences much better than demographic attributes.

• European fringe political parties still have mild to moderate room for growth.

• An effective way to mitigate the salience of anti-immigrant sentiment is to re-orient

nationalism to justify the future admission of foreigners.

Executive Summary

Over the last decade in European politics, the fringe has become mainstream. European voters have redistributed electoral power to a greater share of far-right and far-left fringe parties than the Continent has seen in its democratic history, and these parties are becoming an increasingly normalized part of the political landscape. In May 2019, this trend crested in European elections when far-right, nationalist parties increased their share of European Parliament seats from 20 percent to about 25 percent. At the national level, far-right parties now control more than a tenth of the national legislature in most European countries, and fringe party leaders from the left and right have entered into government in Austria, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia.

What is driving this shift away from center-left and center-right parties? Evidence from contemporary political research is filled with contradictory findings for two principal reasons. First, fringe parties on the far left and the far right are rarely examined together. And second, the vast majority of earlier studies look at specific countries or a small number of cases. To address these shortcomings, the International Republican Institute commissioned standardized surveys of nationally representative samples in 19 European countries: Austria, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. With a combined sample of 20,896 European adults, the poll collects a variety of information about respondents’ demographic attributes, political and electoral preferences, and social and economic attitudes.

In this report, we present a variety of polling data about the favorability of parties in each country, along with descriptive differences between respondents according to their political preferences. We also use multivariate regression to estimate the relationship between demographic and attitudinal factors and support for the far left and far right. Unlike many other studies of European political preferences, this study not only collects data from a remarkably broad set of countries, it also considers populism as both a far-left and far-right phenomenon and investigates its specific and collective drivers to better understand what may mitigate or enhance its proliferation.

This study’s most striking conclusion is that illiberalism unites both far-left and far-right voters. To the extent that populism is a coherent phenomenon, it appears to be driven by an illiberal response to aspects of globalization — neoliberalism for the far left, demographic change for the far right. Of course, far-left and far-right responses diverge, as the latter seeks more authoritarian measures against immigration and minorities, while the former seeks a revolution against capitalism. Correspondingly, attitudinal explanations for fringe party support also diverge. While far-left support is correlated with low levels of ethnocentrism and faith in public institutions, far-right support is correlated with high ethnocentrism, inflated estimates of demographic change, and distrust of public institutions. Importantly, all attitudinal factors explain party preferences much better than demographic attributes.

Based on these findings and statistical models, we predict the untapped potential support for fringe parties in Europe by assessing the proportion of people who fit the profile of fringe party supporters but do not yet support fringe parties. The results demonstrate that these political movements still have some room for growth. In particular, far-right parties appear poised for growth in a number of mostly Eastern countries where they already hold a significant amount of power (Estonia, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Slovenia) and Western European countries with far-right parties that have yet to access power (Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden). Our estimates project mild gains for the far-right, and potentially substantial gains for some far-left parties, if their mainstream counterparts are unable to retain their voters.

To better retain support, our research finds counterintuitive promise in the logic of nationalism. Using an experimental design, we conclude that an effective way to persuade more Europeans to support future immigration is to connect foreigners’ admission to the maintenance of the nation — the very nation that nativists claim immigrants threaten. Doing so significantly increases the share of Europeans who support admitting more immigrants. Our findings appear to be pressurized by the coronavirus pandemic, which made those Europeans most worried about the spread of disease less inclined to change their views about immigration and more inclined to grant greater powers to governments.

Europe’s Path Back from the Fringe

Over the last decade in European politics, the fringe has become mainstream. European voters have redistributed electoral power to a greater share of far-right and far-left fringe parties than the Continent has seen in its democratic history, and these parties are becoming an increasingly normalized part of the political landscape.

In May 2019, this trend crested in European elections when far-right, nationalist parties increased their share of European Parliament seats from 20 percent to about 25 percent. Though far-left parties suffered some losses, the far-right formed a new and larger bloc called Identity and Democracy (ID), which is anchored by Italy’s The League and France’s National Rally and now contains 75 voting members from 10 countries. ID does not currently include representatives from Poland’s Law and Justice Party or Hungary’s Fidesz, which separated from the center-right European People’s Party in March 2021 and remains the only party to win a majority of its country’s European delegation seats.

At the national level, far-right parties now control more than a tenth of the national legislature in countries including Austria, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden. In this study, we poll nationally representative samples from each of these countries along with representative samples from other countries that have also seen increased support for fringe parties—France, Lithuania, and the United Kingdom. In these 19 countries, far-left parties have voting members in the national parliaments of Denmark, France, Germany, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. In the last decade, fringe party leaders from the left and right have been elected prime minister in Hungary (Viktor Orbán), Greece (Alexis Tsipras), Poland (Mateusz Morawiecki, Beata Szydło, Jarosław Kaczyński), and Slovakia (Robert Fico, Peter Pelligrini), and have entered prominently into coalition governments in Austria, Italy, and Latvia. Their presence is increasingly normalized. (For a list of recent election results, see Appendix Tables A.1 and A.2)

What is driving the shift away from center-left and center-right parties? To address this question, we must think of far-right and far-left parties as part of a coherent phenomenon to be considered together. Numerous observers have characterized the recent wave of fringe successes as populist in nature. While populism orients the far-right and far-left in opposition to a purportedly corrupt elite establishment and in solidarity with a purportedly virtuous people,1 it says little about their shared approach to policy or the composition or attitudes of their supporters. And a closer look reveals that little connects fringe parties beyond their populist orientation. Even fringe parties among the left and the right tend to differ greatly in their platforms and worldviews.2 As center-left and center-right parties consider how to retain and recover their voters, variability on the fringe has made it difficult to develop a coherent political strategy in response.

Different Drivers

Stemming from the variety of fringe parties across European countries, there is a wide range of theories about their appeal. These may be categorized into three broad understandings. One group of observers argues that fringe party voting is the product of economic grievances related to growing inequality and diminished socioeconomic stability.3 A second group of observers relates fringe party support to a sense of cultural threat derived from the presence of ethnically and religiously diverse immigrants perceived to be altering national identity and dominant ethnic and religious groups’ social status.4 A third group attributes support for fringe parties with a desire for greater political accountability, transparency, and popular control.5 A number of others connect these strands together.6

As this brief summary suggests, the field is filled with contradictory findings. There are two principal reasons why. First, fringe parties on the far left and the far right are rarely examined together.7 While the far left and far right share a populist ethic, their policy goals and demographics are sufficiently divergent that it is reasonable to expect similarly divergent drivers for their support. So there may be little reason that earlier studies of the far right would hold implications for our understanding of the far left, and vice versa. Second, the vast majority of earlier studies look at specific countries or a small number of cases.8 The European political space is remarkably diverse, with a variety of political parties and constituencies that make it challenging to generalize from one region to another without empirically studying them all.

Methods

To address these shortcomings, the International Republican Institute commissioned standardized surveys of nationally representative samples in 19 European countries. The poll was conducted among 20,896 European adults aged 18 and older who responded online in their national language in an Ipsos survey conducted in August 2020. The sample was drawn from Ipsos’ online panel and its partners after the sample was obtained, respondent characteristics were statistically calibrated to be representative of national populations using standard survey adjustment procedures based on each country’s population distribution on gender, age, occupation, region, and population density.

The poll collected a variety of information about respondents’ demographic attributes, political and electoral preferences, as well as social and economic attitudes. While we present the descriptive differences between respondents according to their political preferences, we also use multivariate regression to estimate the relationship between demographic and attitudinal factors and support for far-left and far-right parties in each country. Unlike many other studies of European political preferences, this study not only collects data from a remarkably broad set of countries; it also considers populism as both a far-left and far-right phenomenon and investigates its specific and collective drivers.

Parties and Elections

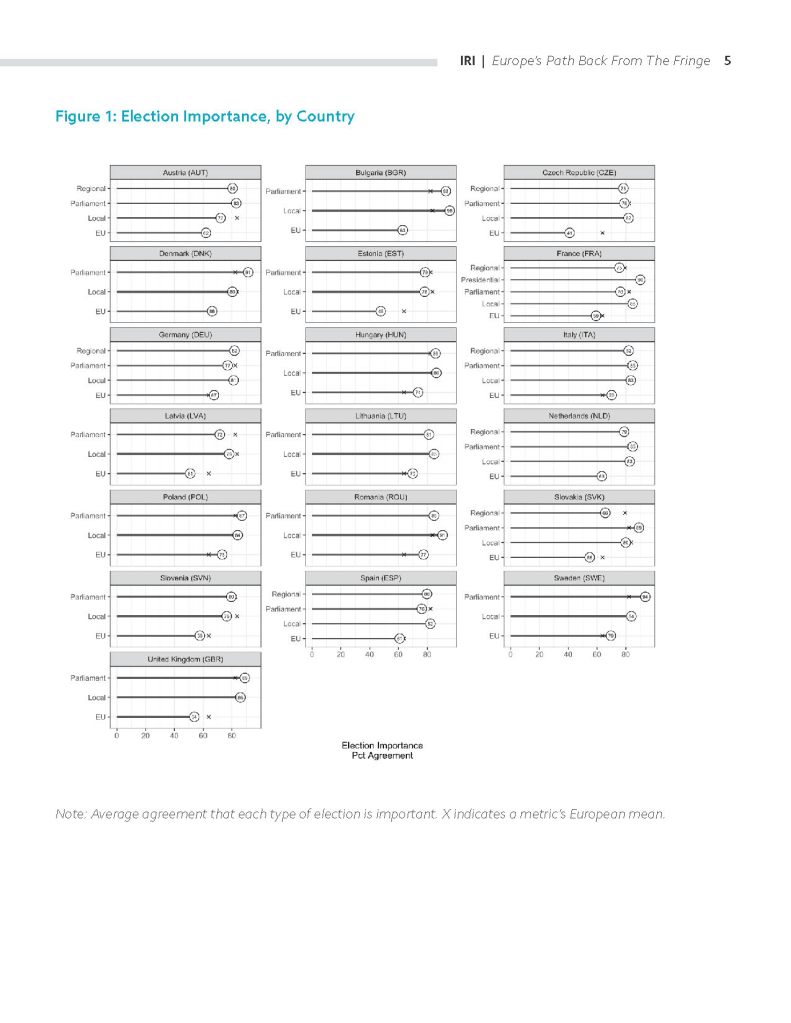

Figure 1 contextualizes different countries’ views about the relative importance of multi-level elections. When asked to indicate the importance of various levels of elections, parliamentary, regional, and local elections emerged with the highest average level of perceived importance, nearly 20 points higher than the importance of European elections. European elections were perceived to be important by Hungarians, Italians, and the Polish — all of whom have recently sent Euro-skeptic delegations to Brussels — along with Romania, Lithuania, and Sweden. Perceived importance was lowest in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, and the United Kingdom — which, of course, recently

left the European Union. The importance of parliamentary elections was highest in Sweden, Bulgaria, Denmark, and Slovakia and lowest in Latvia, Spain, the Czech Republic, and France —which features an influential presidential election — but elsewhere fell near the mean. The importance of regional elections was highest in Austria, Germany, and Italy. Local elections had elevated importance in Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary, but were less important in Austria, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

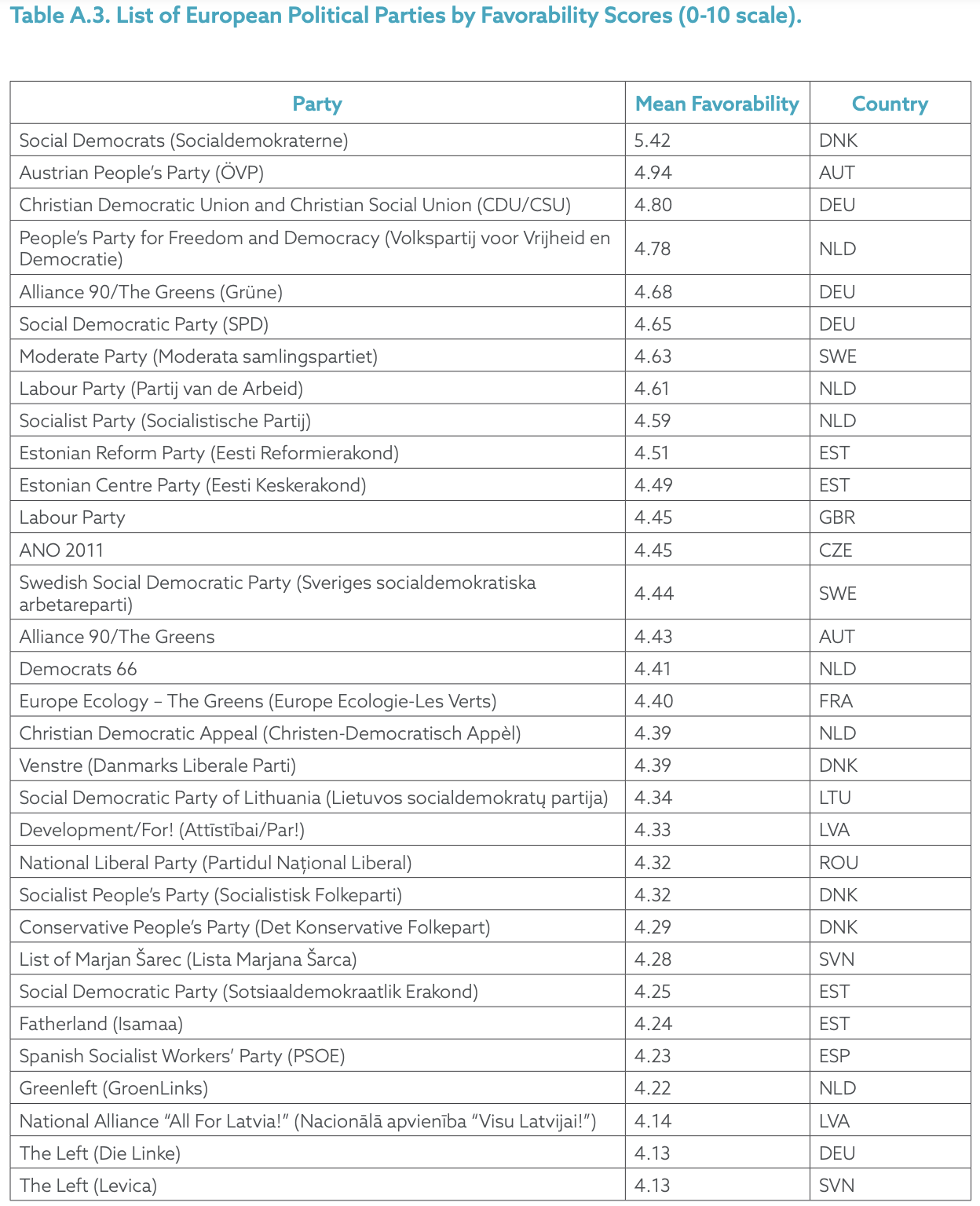

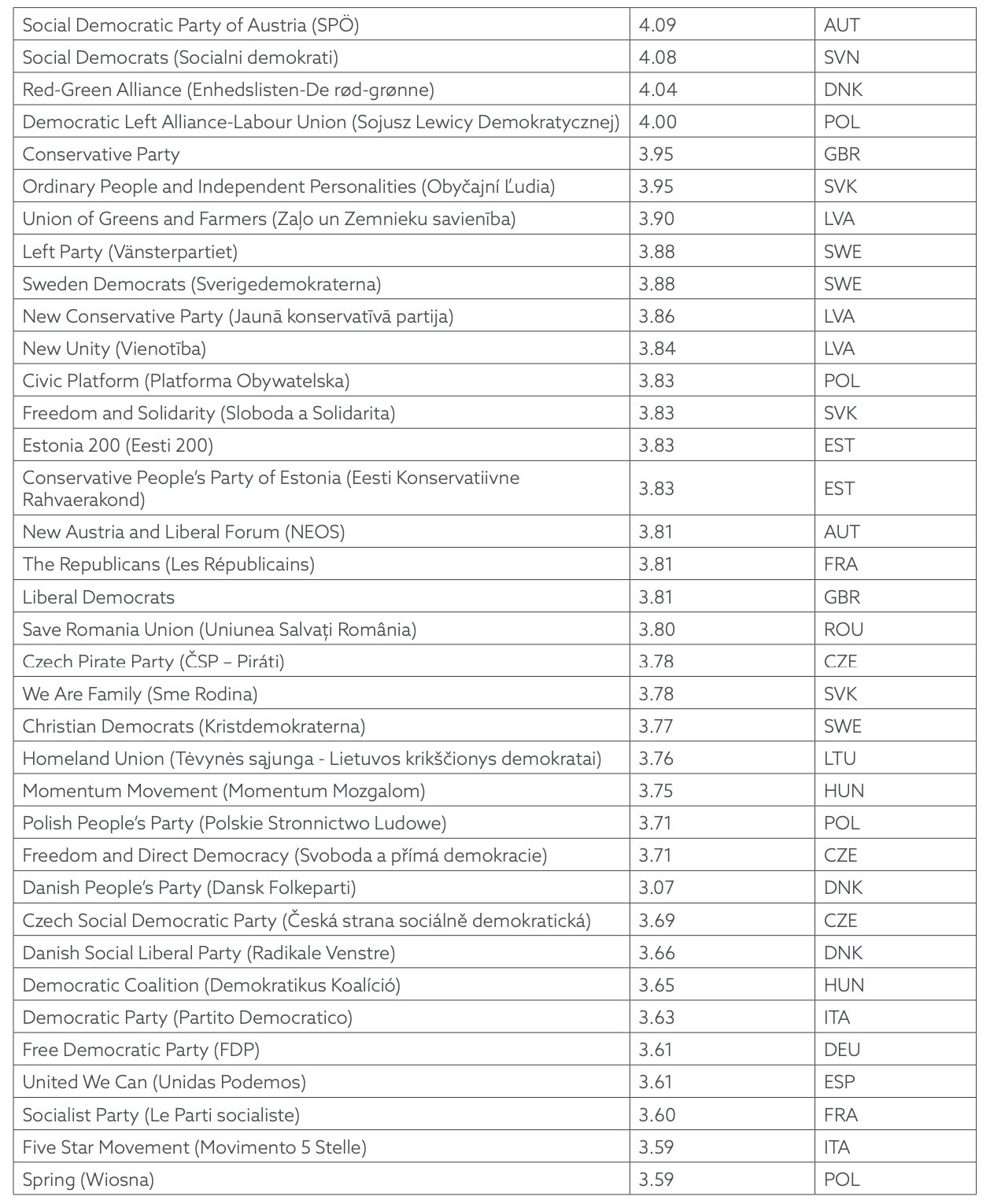

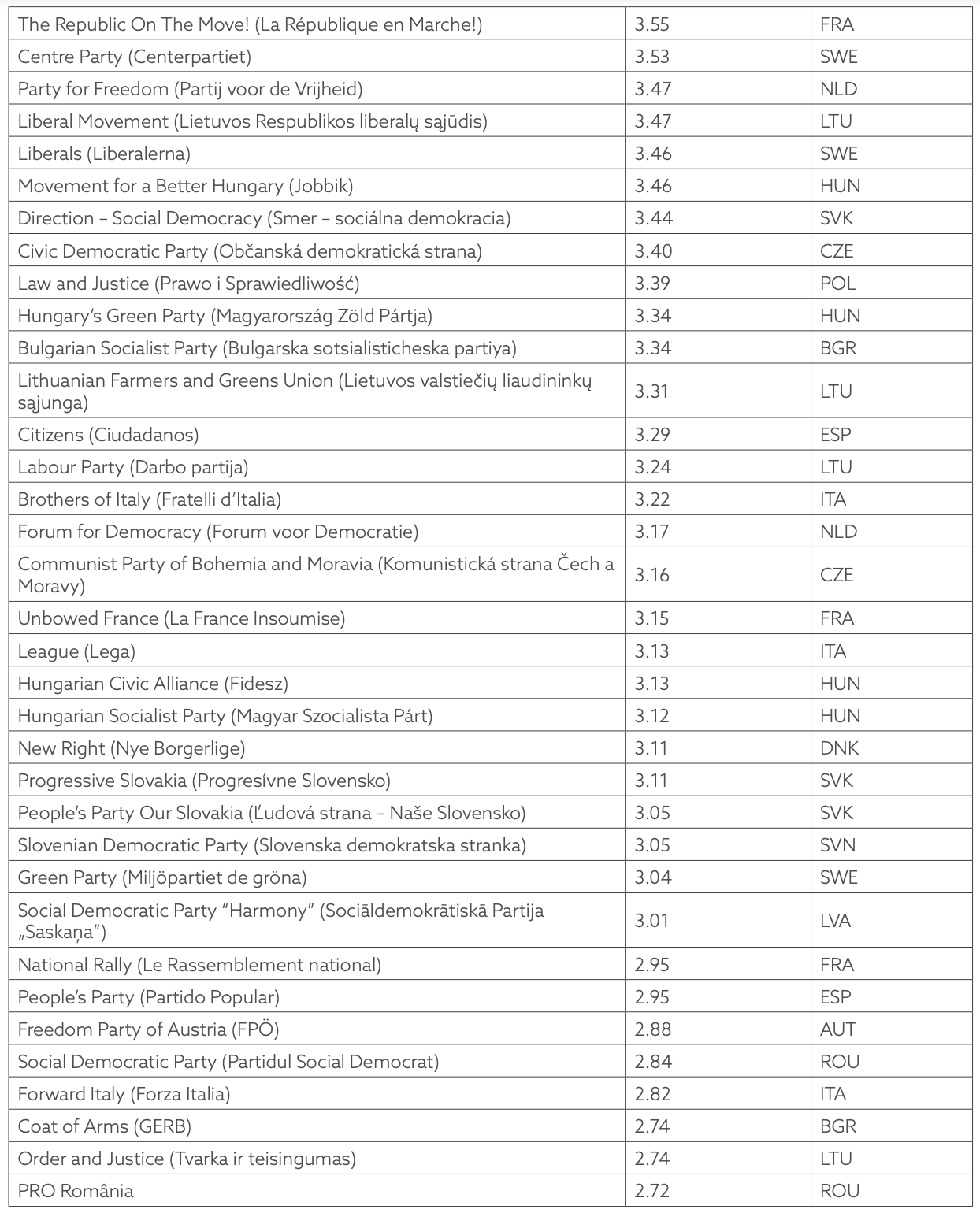

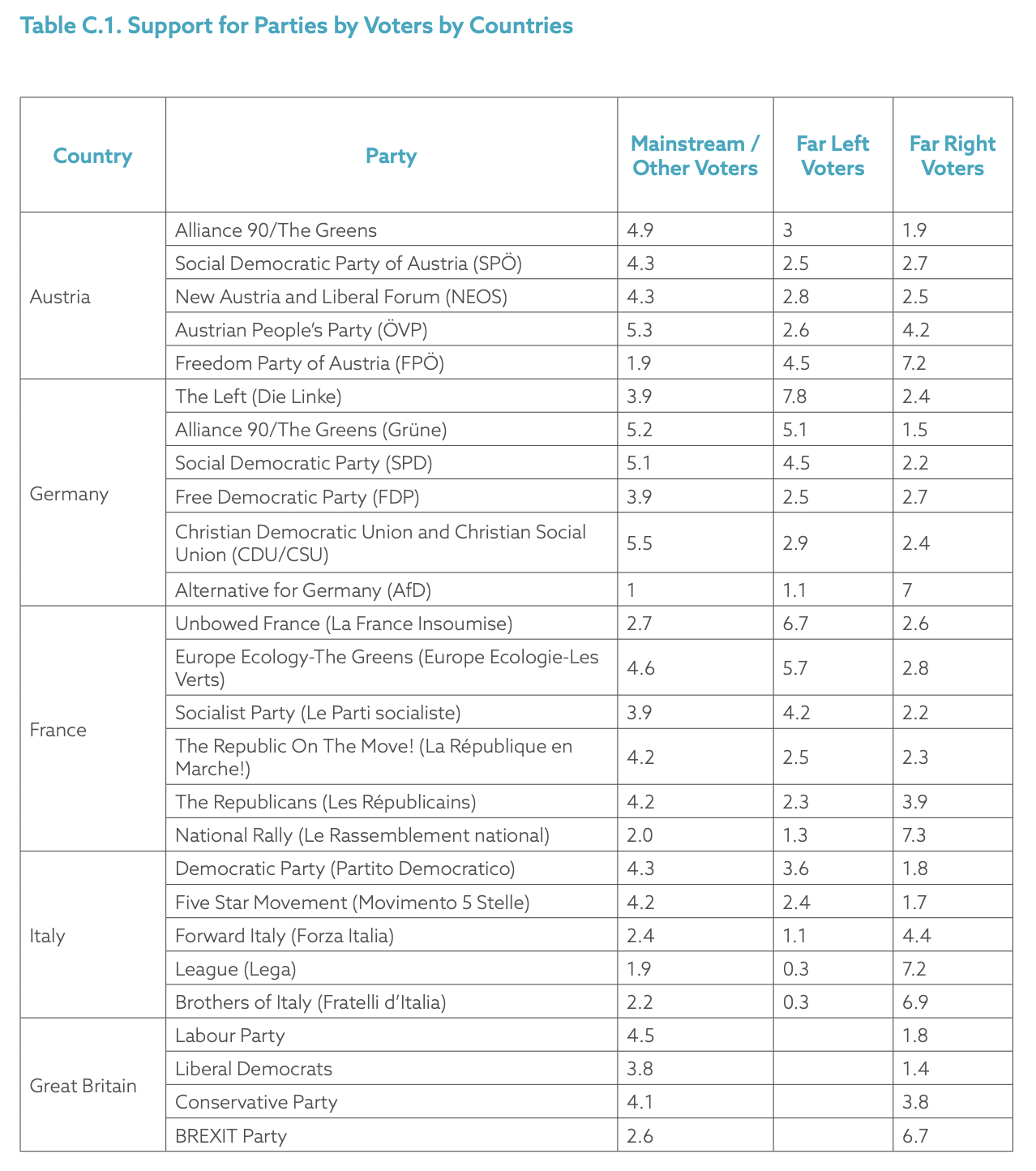

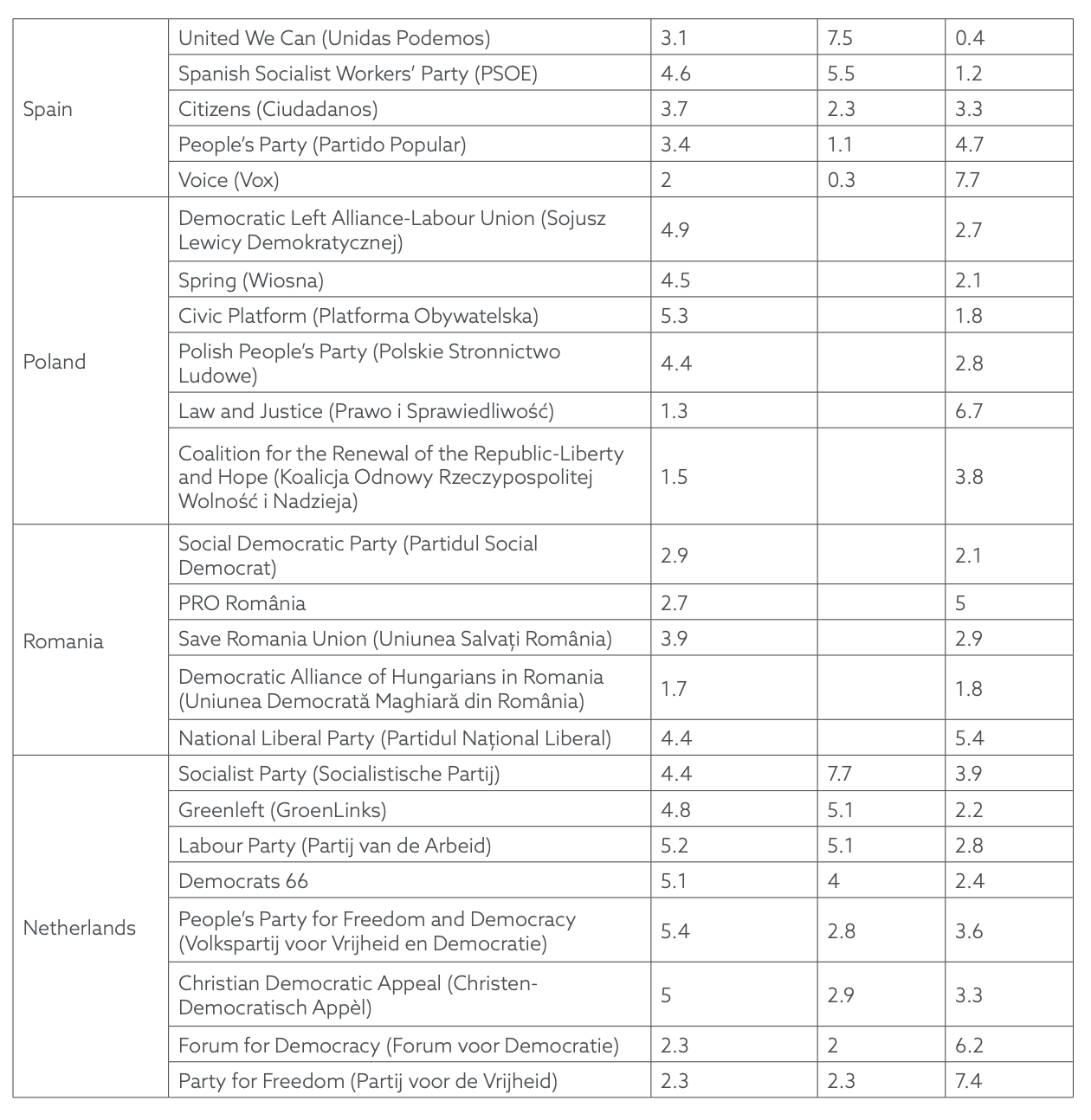

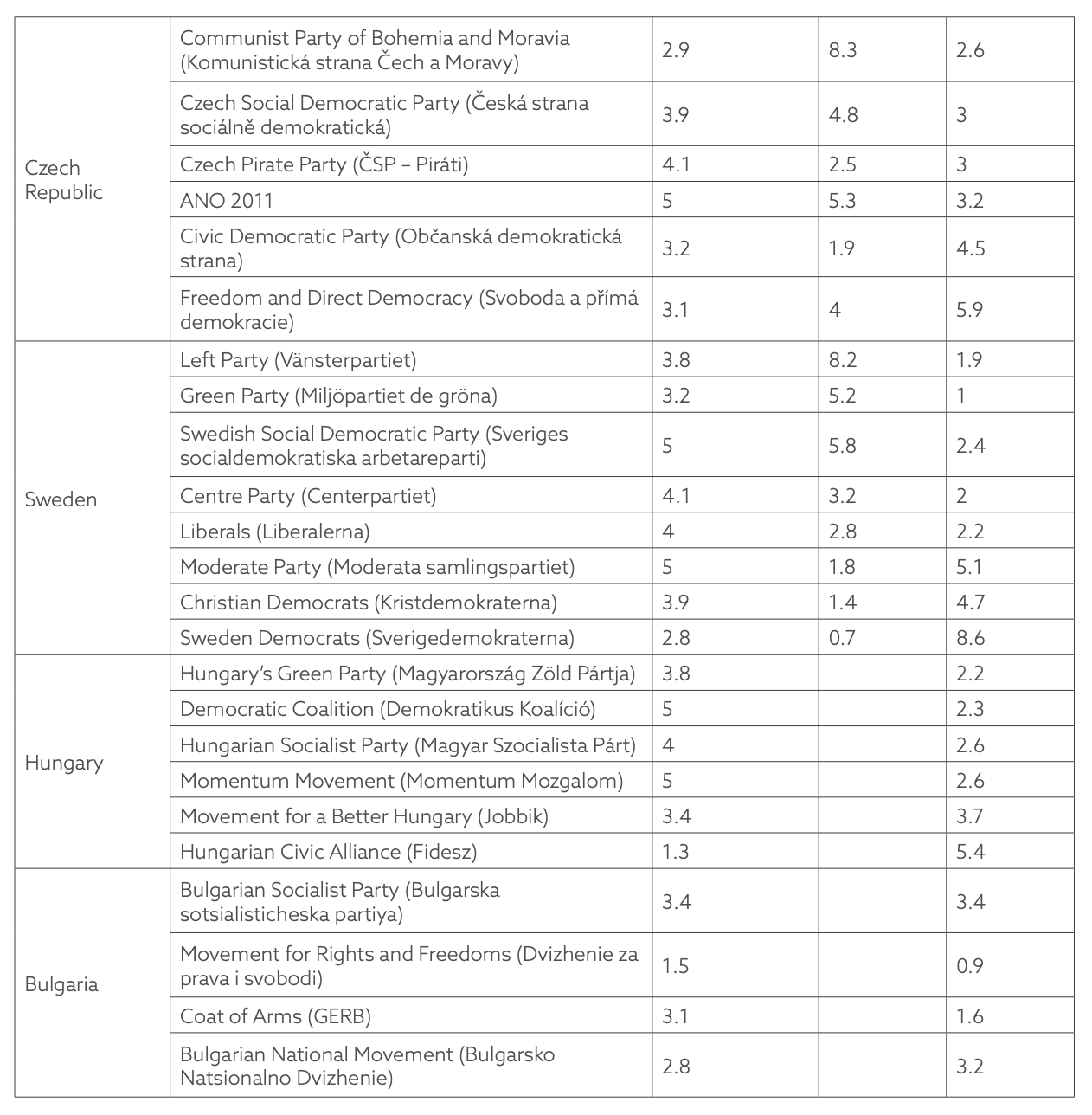

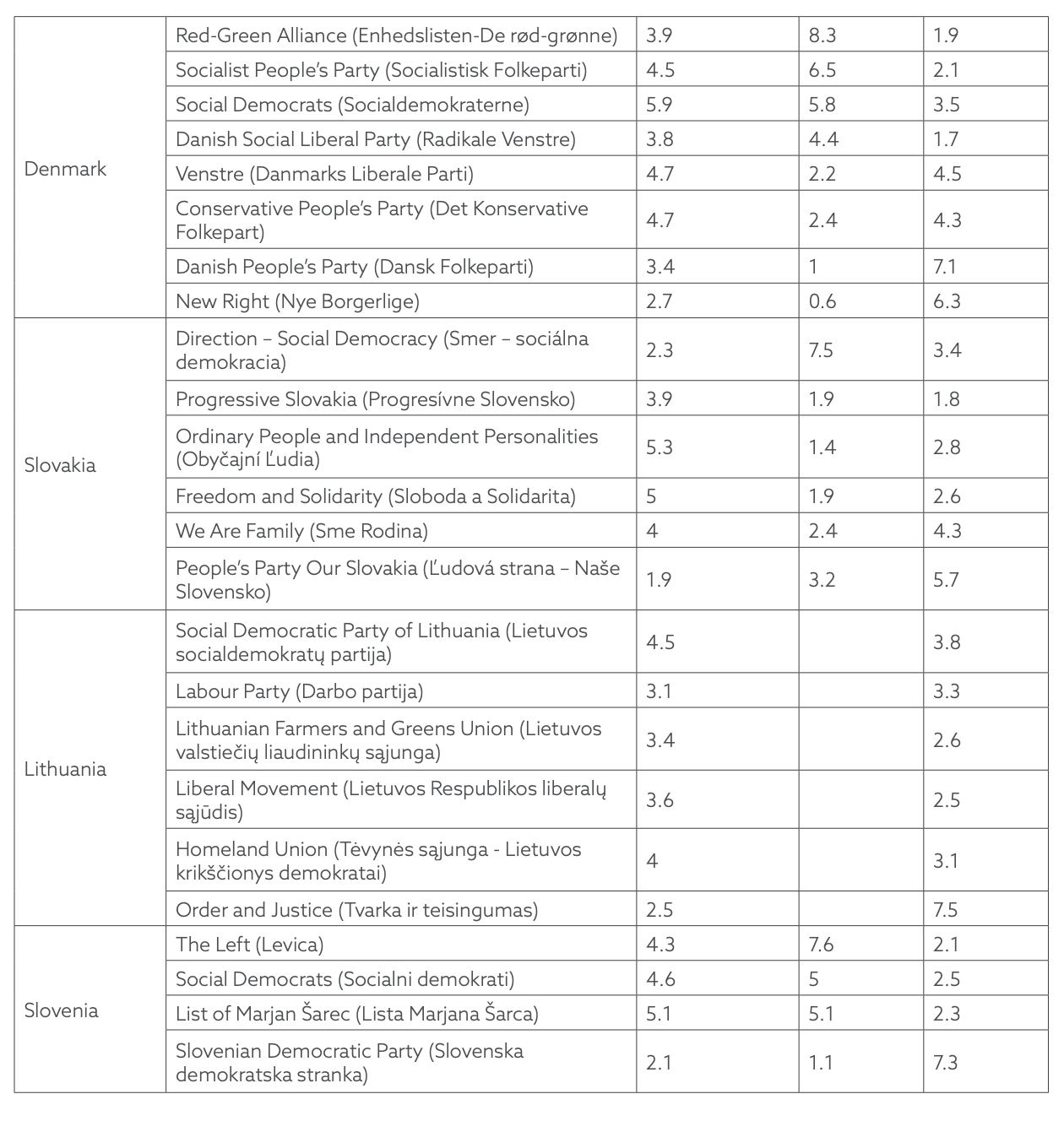

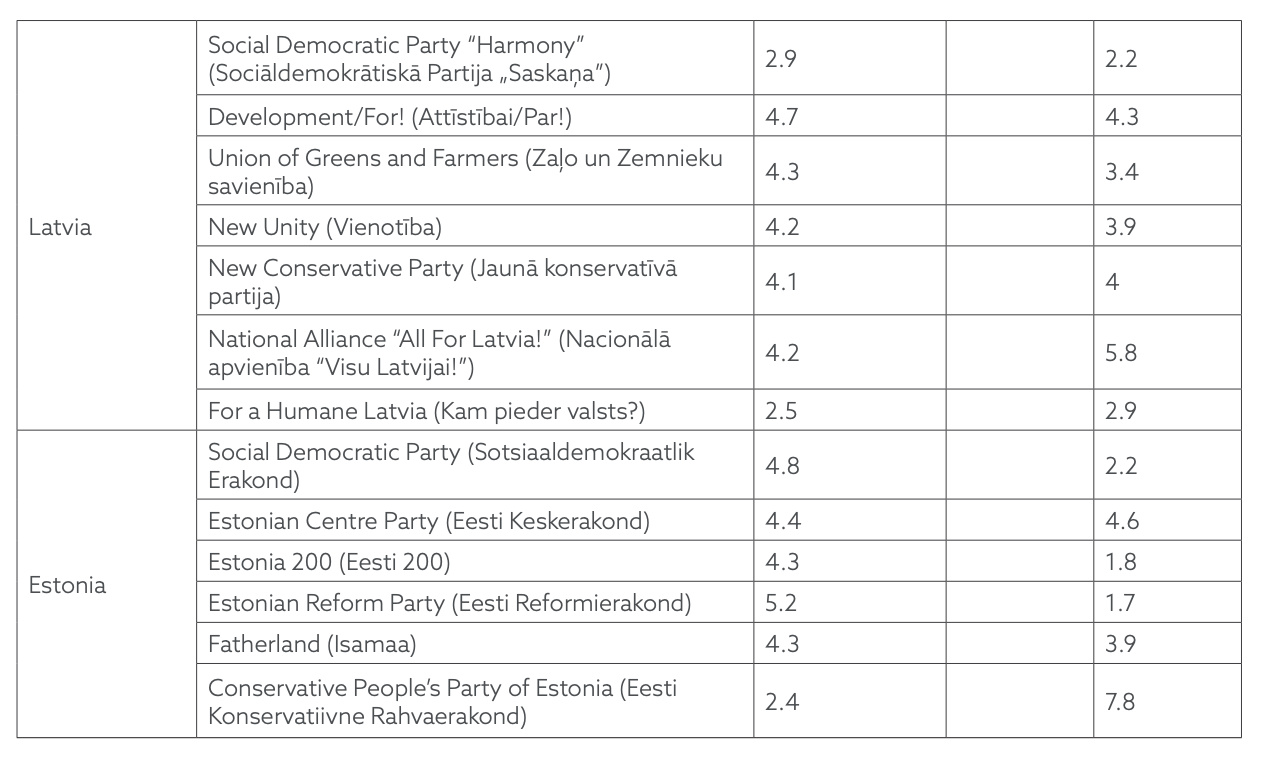

We measure favorability ratings on a 0 to 10 scale for all major parties across the full sample from the 19 countries (Appendix Table A.3). To be clear, unlike the vote shares above which are limited to people who report voting, we measure favorability among non-voters as well. These scores are less predictable. While in some cases ruling parties are viewed favorably in a manner that reflects their vote share, in other cases ruling parties’ favorability scores are lower than their counterparts in the opposition. This may reflect the burden of being in government, but also local subjectivities. The top four favored parties across the Continent are Denmark’s Social Democrats — who assembled a governing coalition in the Folketing in 2019 — and center-right parties leading governments in Austria (ÖVP), the Netherlands (VVD), and Germany (CDU/CSU). Interestingly, the next most favored parties are Germany’s Social Democrats and Greens, which suggests a greater baseline level of German satisfaction with political leaders across the spectrum. As a counterexample, baseline levels of favorability are much lower in Bulgaria and Italy, where even the most popular parties are at or below the European mean (3.62).

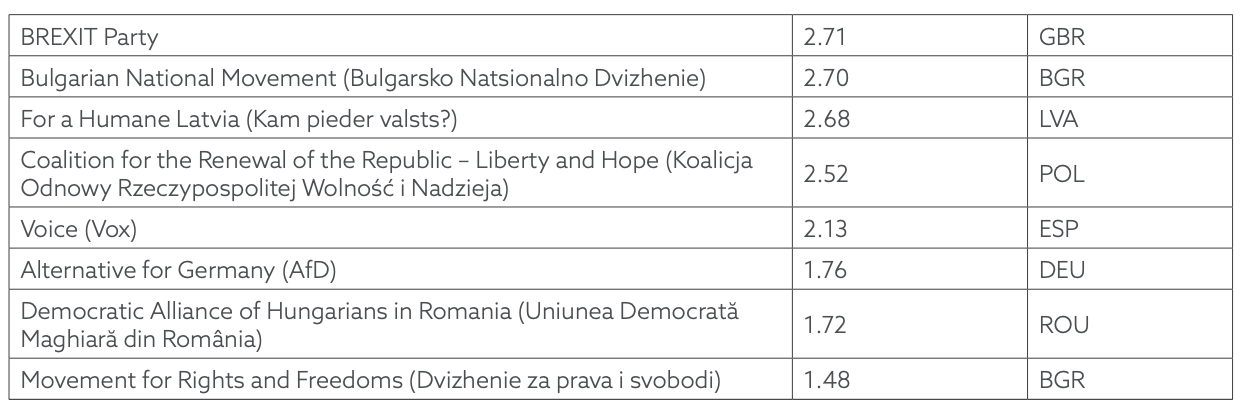

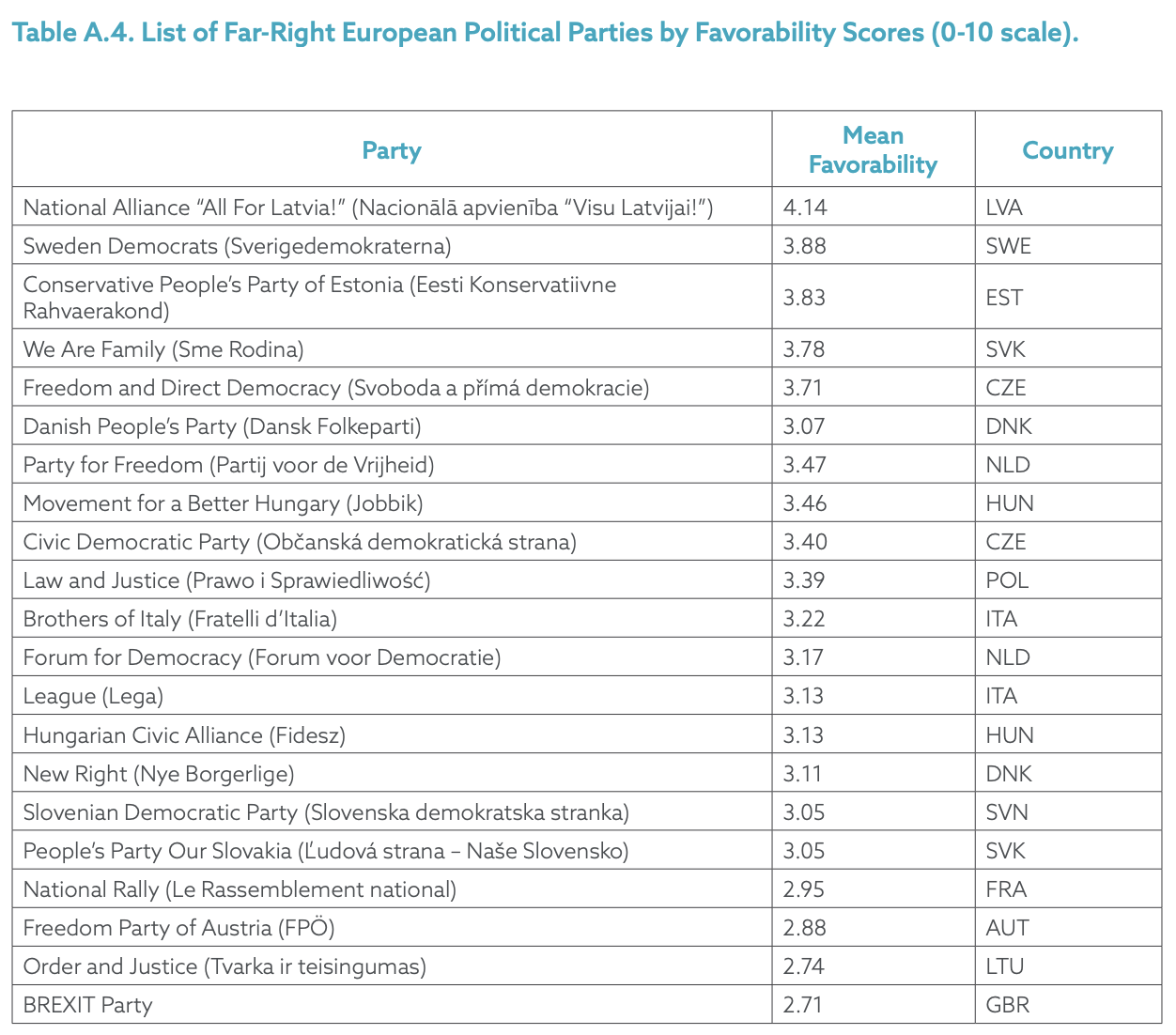

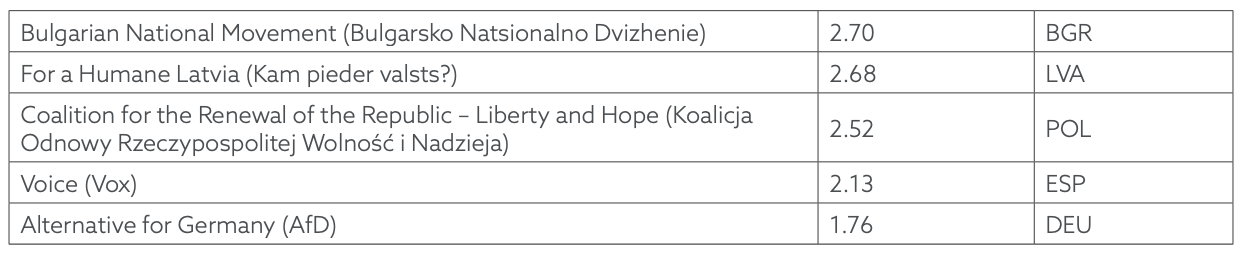

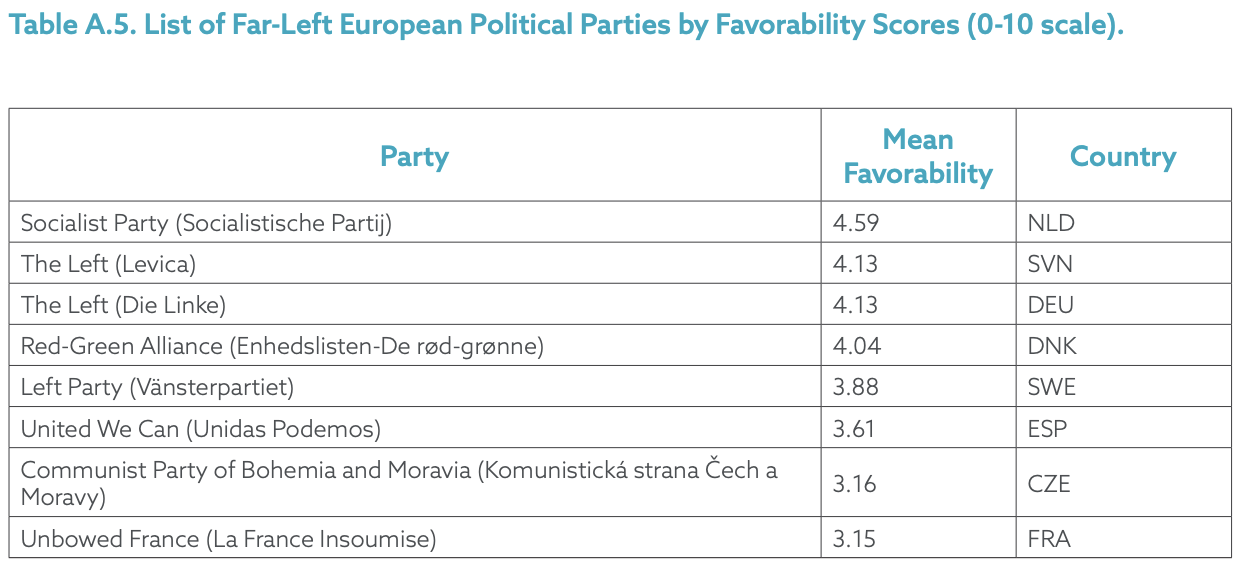

On the fringes, favorability remains significantly lower for far-right parties (Table A.4). Only six parties are favored above the European mean — Latvia’s National Alliance, Sweden Democrats, Estonia’s Conservatives, We Are Family in Slovakia, Freedom and Direct Democracy in the Czech Republic, and the Danish People’s Party. A number of far-right parties receive some of the lowest favorability scores among the countries under study, including Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland and Spain’s Vox — which are stigmatized in countries with a history of fascist governments. Far-left parties (Table A.5) are subject to much less popular rejection. Six out of the eight parties in the case countries are rated above the European average with relatively high scores for the Dutch Socialists, Slovenia’s Left, Germany’s The Left, and the Red-Green Alliance in Denmark. Still, the data reveal the extent to which Europe’s proportional representation system — which allocates parliamentary seats by vote share rather than winner-takes-all, single member district elections — amplifies the power of fringe parties. While there are certainly institutional reasons that fringe parties have succeeded in Europe,9 we are more concerned with the demographic profiles of their supporters and the public attitudes correlated with their success within Europe’s institutional framework.

Demographic Profile

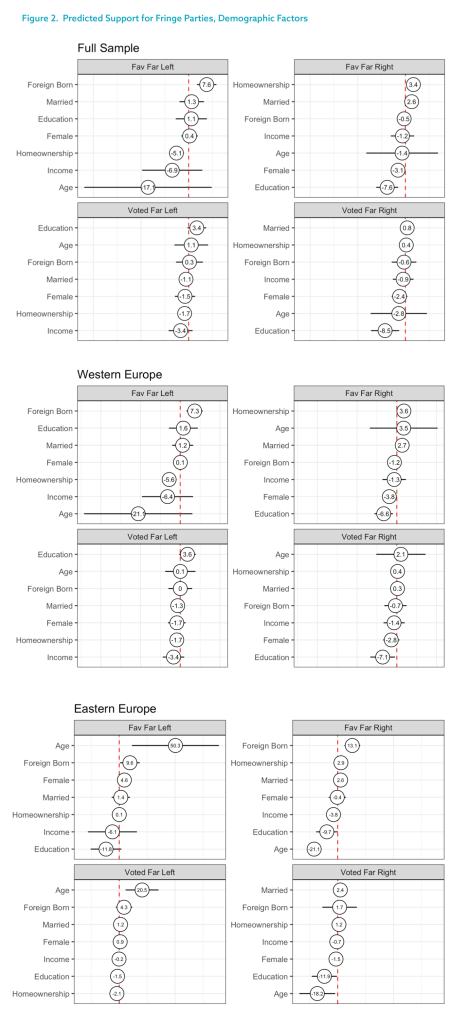

Demographically, the far-right and far-left attract different constituencies. Across all 19 countries, the demographic attribute that most powerfully predicts an individual’s support for a far-right party is their level of formal education (Figure 2). Across all 19 case countries, respondents with higher educations were 7.6 percentage points less likely to view the far-right favorably and were 8.5 percentage points less likely to vote for a far-right party. This working class appeal of the far-right has been well documented10 and inspires the anti-elite, populist approach of many parties. However, the data offer a more nuanced portrait of fringe party supporters. Other predictors of the far-right favor relate to whether respondents own a home (3.4 percentage points more likely) or are male (3.1 percentage points more likely).

Similarly, far-left support is also predicted by education level, but inversely. People with higher educational backgrounds are 3.4 percentage points more likely to vote for far-left parties. Other predictors of far-left favor relate to whether respondents are homeowners (5.1 percentage points less likely) or foreign-born (7.6 percentage points more likely). These Europe-wide trends predominate in Western Europe. They are less visible in Eastern Europe, where far-right support is more common among young people and far-left support is more common among older people.

Fringe Attitudes

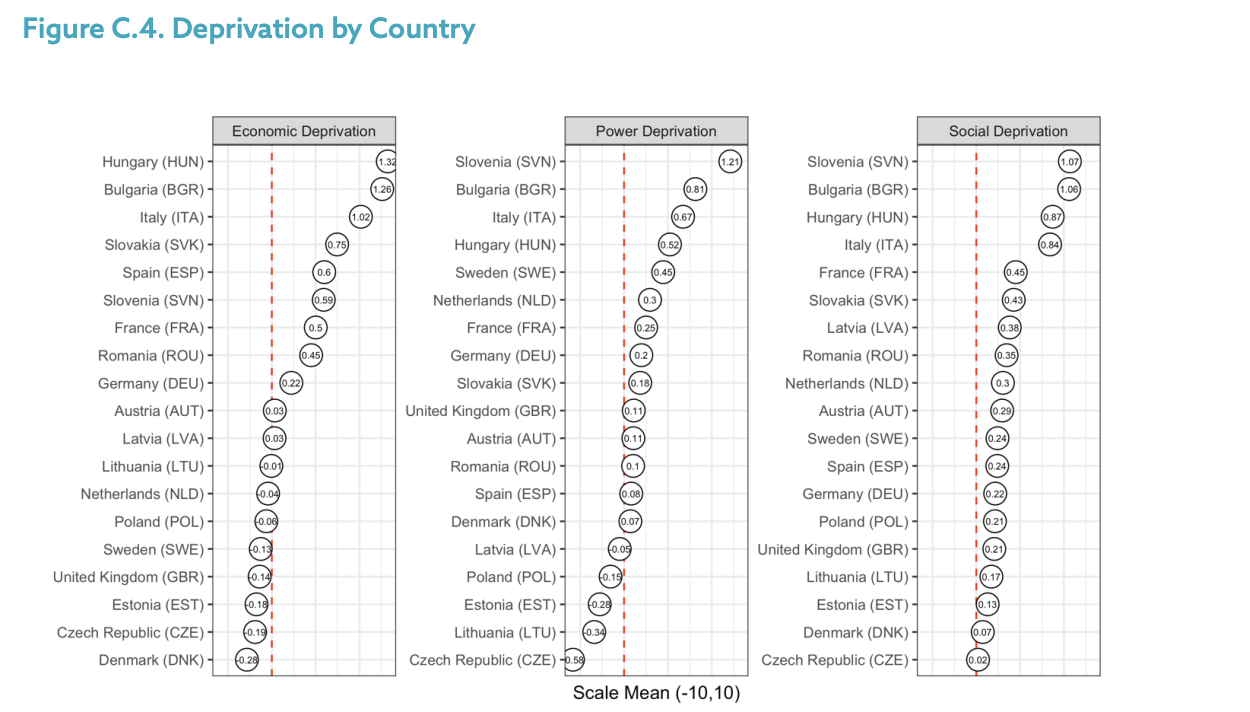

Previous analyses of fringe party support in Europe center on the role of economic grievances, perceptions of cultural threats, and anti-establishment perspectives. In this study, we study each of these in isolation, but we also regress support for the far-left and far-right on a series of demographic and attitudinal variables to estimate the relationship between each. To account for economic grievances, we use a measure of economic deprivation that solicits respondents’ sense of lost financial status over the last 25 years.11 To account for perceptions of cultural threat, we employ an ethnocentrism battery that solicits respondents’ views about the growth of ethnic and religious diversity, national identity, and assimilation. To account for anti-establishment perspectives, we employ a populism battery that taps into anti-elite sentiment but also metrics of institutional trust. Additionally, we use an authoritarian personality battery which taps into orientations toward obedience to external powers.

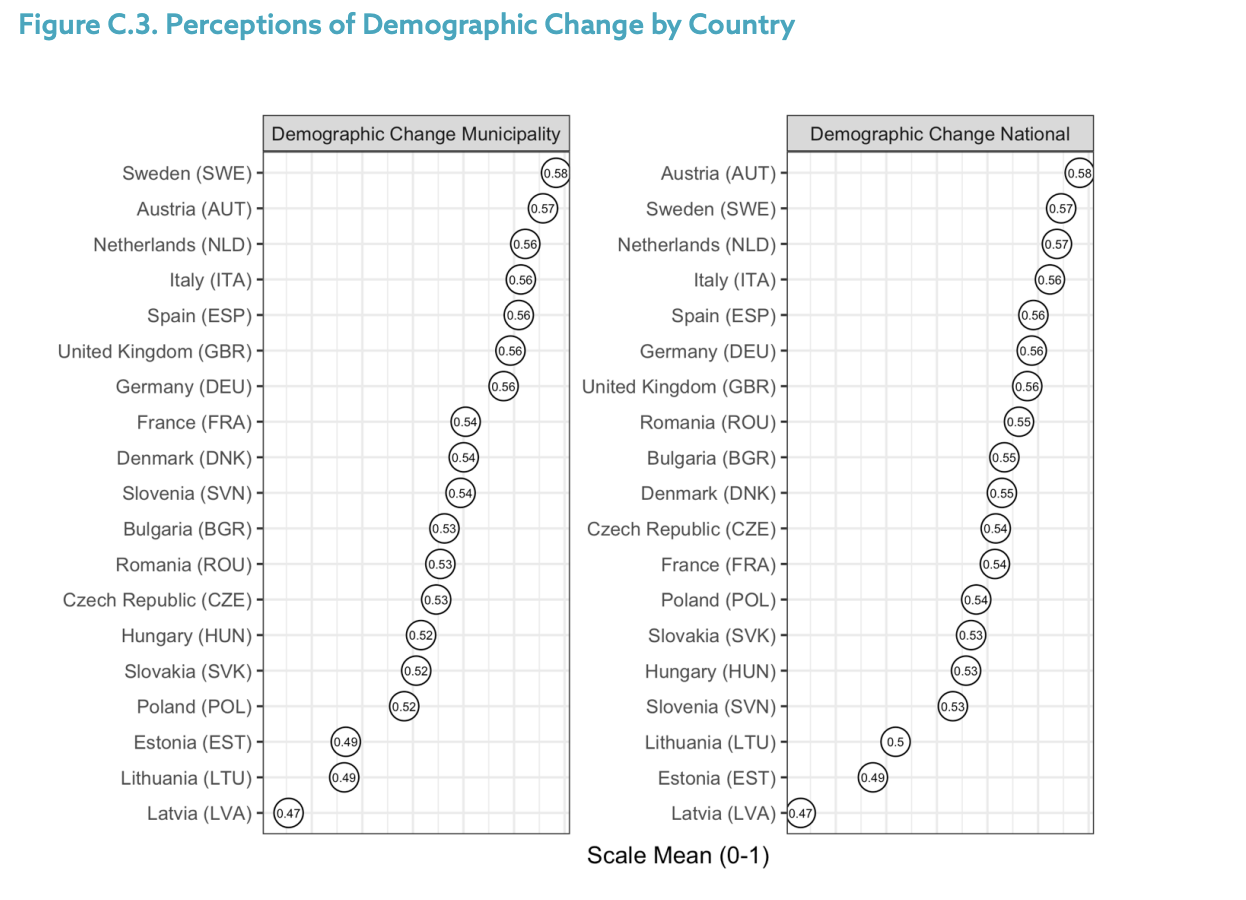

However, we also incorporate a variety of novel metrics to account for alternative hypotheses about the attitudinal drivers of fringe party support in Europe. We hypothesize that there may be a relationship between far-right voting and exaggerated perceptions of demographic change,12 so we solicit respondents’ estimates of demographic change in both their municipality and their country over the last 25 years. Next, we hypothesize that there may be a relationship between the sense of lost political power or lost social status and fringe party support.13 To test this, we ask respondents to separately indicate how much political power and social standing they hold today, and how much people like them held 25 years ago — measures of nostalgic power deprivation and social deprivation, respectively. Finally, we hypothesize that there may be a relationship between liberal or illiberal political orientations and fringe party support,14 so we solicit respondents’ approval or disapproval of a variety of state actions that violate minority rights, suspend voting rights, break secular norms, infringe upon freedom of speech, and threaten judicial independence. Responses are then scaled into a measure of illiberalism. Full details on scale construction can be found in Appendix B.

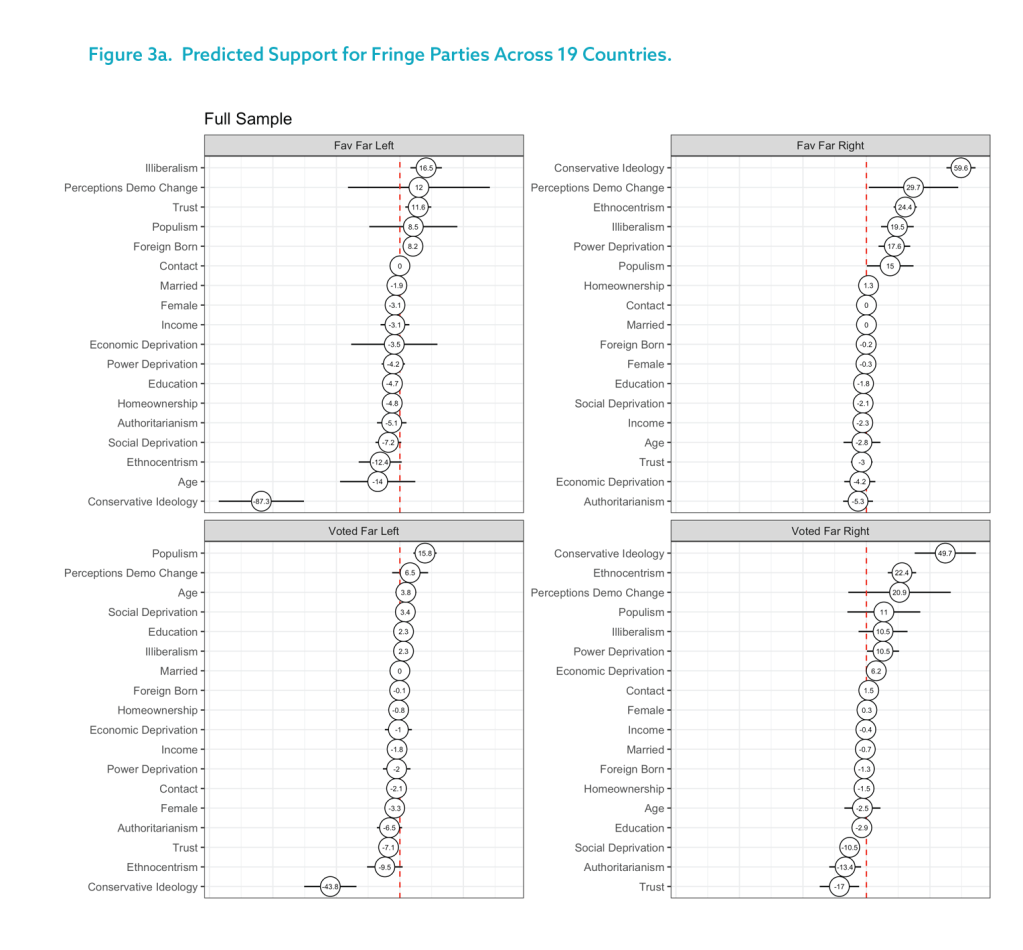

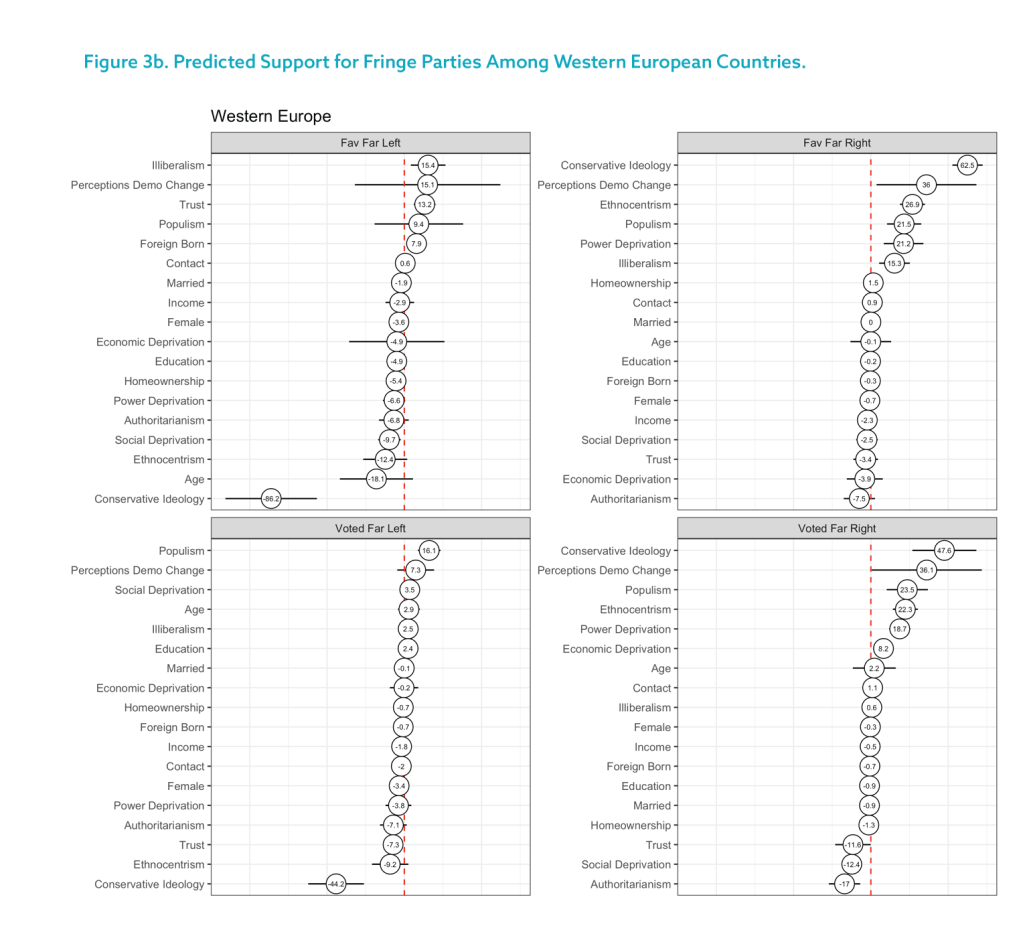

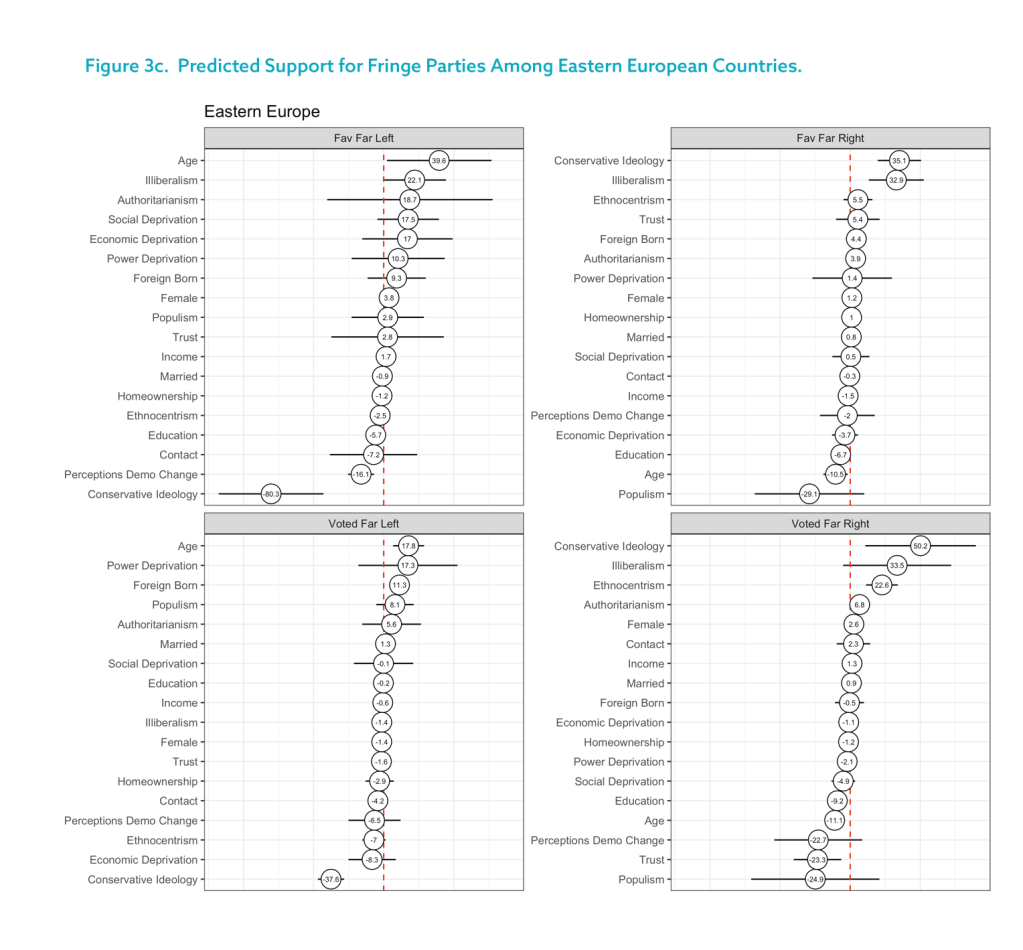

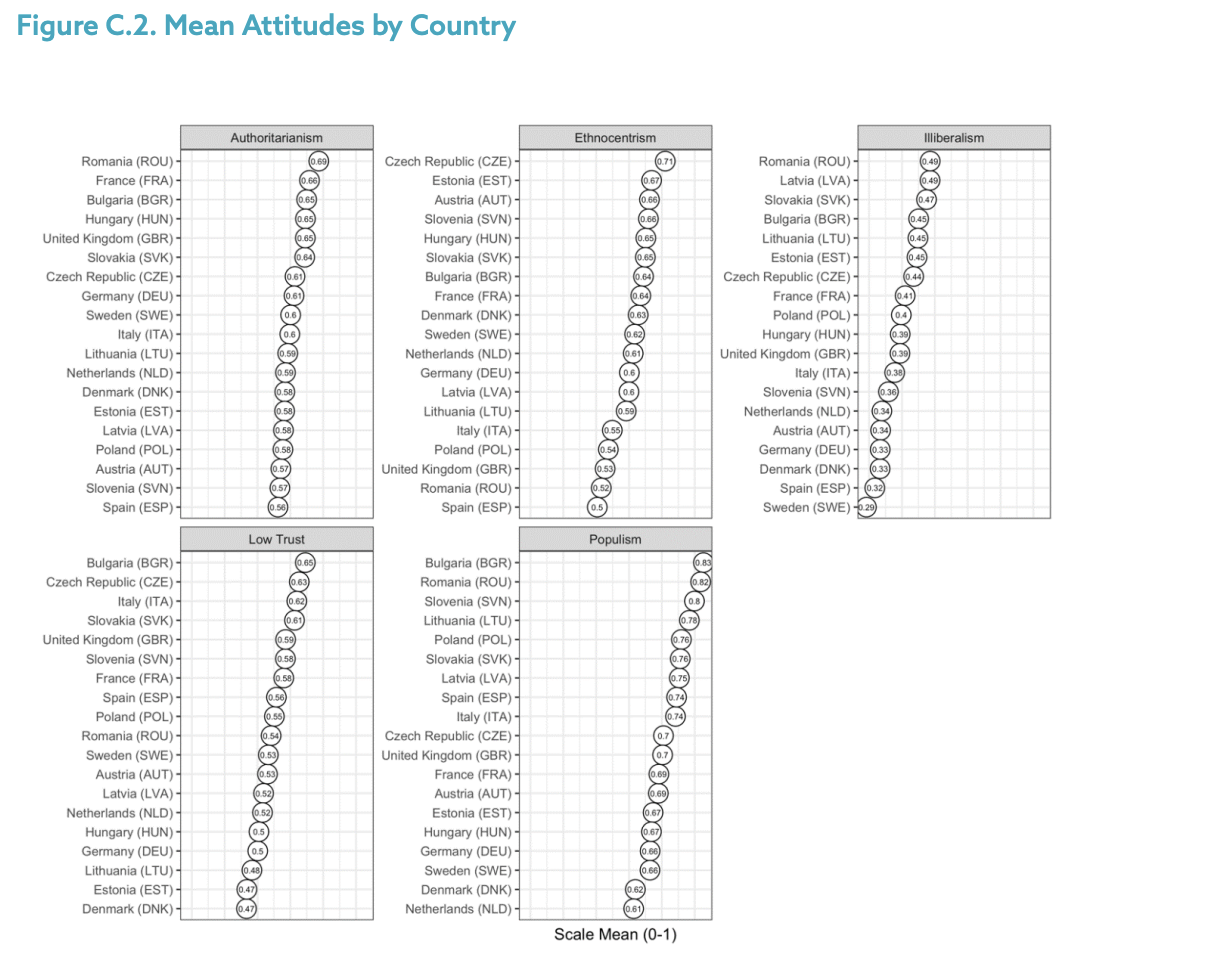

The modeling exercise allows us to observe the effect of these different attitudinal perspectives on the likelihood of support for fringe parties, while controlling for a variety of potential explanatory factors. Across 19 countries with a mix of fringe parties (Figure 3a), one principal factor emerges as positively correlated with the favorability of both far-right and far-left parties: illiberalism. People with illiberal orientations are 19.5 percentage points more likely to favor far-right parties and 16.5 percentage points more likely to favor far-left parties. While this trend that holds across Eastern and Western European states (Figures 3b and 3c), it is amplified in the East where people with illiberal views are 32.9 percentage points more likely to favor far-right parties and 22.1 percentage points more likely to favor far-left parties. Perceptions of demographic changes also emerged as strong predictors of support for the far right. Respondents who perceive the greatest increases in the number of foreigners living in their countries are 30 percentage points more likely to favor far-right parties. This finding is amplified in the immigrant destinations of Western Europe, where people that have perceived the greatest demographic shifts are 36 percentage points more likely to vote for far-right parties and 36 percentage points more likely to favor far-right parties.

To put the scale of these results into perspective, they significantly outweigh the correlation between fringe party support and populism metrics, which one might think to be tautological.15 Europe-wide, the most populist respondents are 15 percentage points more likely to favor far-right parties and 15.8 percentage points more likely to vote for far-left parties16. We observe no relationship between populism and favoring the far left or voting for the far right. We also find that the gender gap — which is widely argued to differentiate far-right support — is not predictive once we control for attitudes. Some of the strongest effects related to illiberalism and perceptions of demographic change, particularly in the specific regions, are only eclipsed by the strength of the relationship between fringe party support and left-right political ideology — which unquestionably is a tautology. In sum, if we are to understand what is driving the rush to both of Europe’s political fringes, it is the creeping influence of illiberal ideas and the sense —particularly among some people living in the immigrant destinations of Western Europe — that they are overwhelmed by foreigners.

Of course, the far-left and the far-right have very different reactions to demographic change. Accordingly, their appeal can also be explained by decoupling them and exploring a number of inverse relationships in which opposing attitudes predict either far-left or far-right support. Most prominently, ethnocentrism emerges as integral to explaining these parties’ appeal. Europe-wide, the most ethnocentric respondents are 24.4 percentage points more likely to favor far-right parties and 22.4 percentage points more likely to vote for far-right parties. Inversely, the least ethnocentric respondents are 12.4 percentage points more likely to favor far-left parties and 9.5 percentage points more likely to vote for far-left parties. Less powerfully, there is a similar relationship with institutional trust. Europe-wide, respondents with the highest levels of trust in government institutions are 11.6 percentage points more likely to favor far-left parties, though not more likely to report voting for them. Meanwhile, respondents with the lowest levels of trust are 17 percentage points more likely to vote for far-right parties—a trend consistent across Eastern and Western Europe.

One further dynamic of interest is nostalgic power deprivation — the sense of lost political clout over the last 25 years. Europe-wide, respondents reporting elevated levels of power deprivation are 17.6 percentage points more likely to favor far-right parties and 10.5 percentage points more likely to vote for them. This trend is driven by Western Europeans; those sensing a loss of political clout are 21.2 percentage points more likely to favor far-right parties and 18.7 percentage points more likely to vote for them. While there is no relationship between power deprivation and far-left support Europe-wide, one appears in Eastern Europe. Possibly relatedly, in Eastern Europe, we do find that far-left support is correlated with older voters who may retain doubts about the post-communist era, while far-right support is correlated with younger voters who rely on mediated interpretations of the past. Notably, attitudinal relationships generally outstrip those related to demographic traits, which suggest that demographic characteristics — even education levels and age — cannot profile fringe party supporters as well as certain key public attitudes can.17

Immigrants and Liberal Values

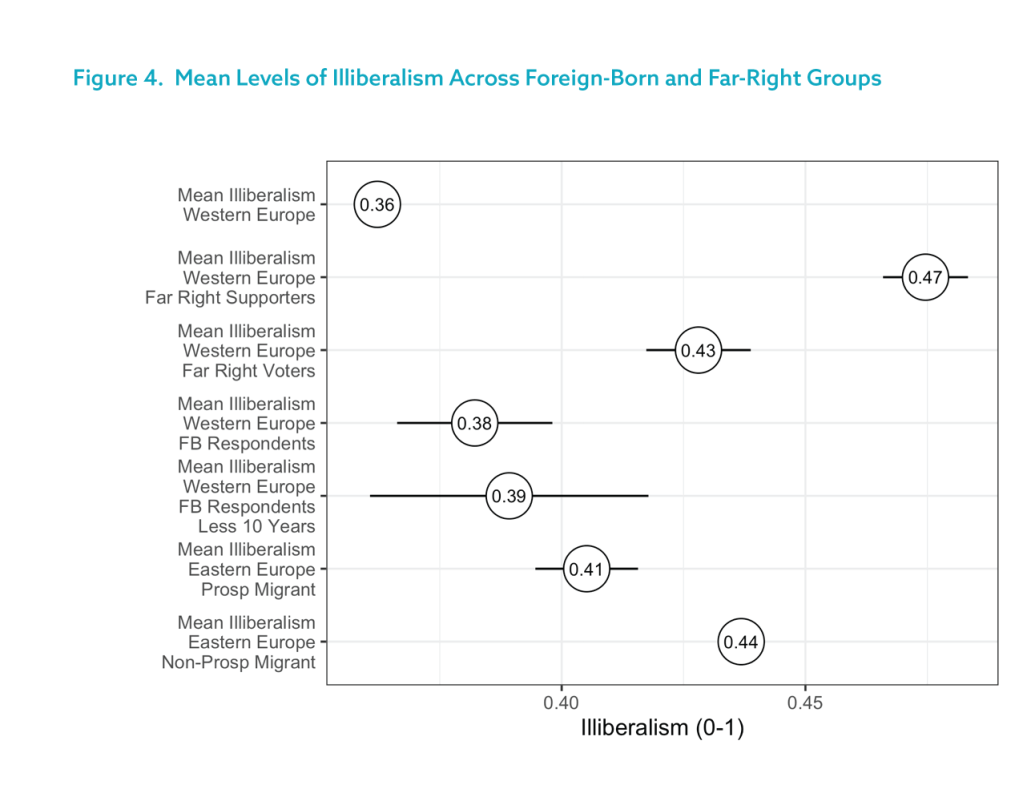

A principal argument against the incorporation of more immigrants into Western European countries by many farright parties and their leaders has been that new arrivals do not align with the liberal values of Western European states. To explore this phenomenon, we begin by comparing the liberalism of prospective migrants from Eastern European countries to the liberalism of their countrymen who do not plan to emigrate. The results demonstrate that prospective immigrants from Eastern Europe are incrementally but statistically significantly more liberal than their countrymen. While the scale of the difference is not large, the scale of East-West migration greatly amplifies its effect. Over time then, migration is depleting Eastern European countries of their more liberal elements.

Of course, the irony is that we earlier find that illiberalism is one of the most significant determinants of Western European support for far-right parties. Are Eastern European immigrants, or any immigrants, any more illiberal in their political views? According to the polling data, no. In Figure 4, the average liberalism score across respondents from all 19 European case countries is 0.36 on a 0 to 1 scale, where 0 is the most liberal and 1 is the most illiberal. We polled foreign-born respondents across the Western European countries who reported an average liberalism score of 0.38, just 2 points more illiberal than the European mean. If we look exclusively at foreign-born respondents who arrived within the last decade and who may be less integrated into Western European value systems, they report an average liberalism score of 0.39. Prospective migrants in Eastern Europe, meanwhile, report an average liberalism score of 0.41 — more liberal than their fellow Eastern European countrymen, but moderately less liberal than the Western European mean. However, when we turn to Western European far-right supporters, they are actually more illiberal than each group of immigrants and prospective immigrants. Those who vote for far-right parties report an average illiberalism score of 0.43, and those who favor far-right parties report an average score of 0.47 — a remarkable disparity from the regional average that nears the average of Eastern Europeans who have no intention of emigrating.

Swing Voters

Some observers believe that the global coronavirus pandemic has undercut populist rhetoric by creating an opportunity for government elites and bureaucrats to demonstrate their value. The pandemic has also made citizens more risk-averse and less inclined toward anti-establishment perspectives at a moment when all are heavily relying on the state for coordination of public health responses. However, the European and national responses to the pandemic have stumbled at times, raising concerns of further backlash against the state establishment and Brussels in future elections. What countries are most susceptible to far-right appeals?

The attitudinal data above offers a useful roadmap. By applying what we know about the attitudinal composition of current far-right supporters, we can better anticipate the “vulnerability” of national populations to future far-right appeals. In Table 1, we assemble each country’s average score on the three attitudinal predispositions that best predict far-right support — illiberal attitudes, ethnocentrism, and perceptions of demographic change. We then add these scores together into a scale of far-right vulnerability (rescaled so that the highest vulnerability score is 1.00) to estimate how fertile public attitudes are toward far-right rhetoric and ideas. We find much higher potential vulnerability toward the far-right in Eastern Europe and much less in Western Europe. This analysis, however, cannot tell us anything about whether those with these attitudes already support the far-right, however, or if they have yet to be persuaded to abandon the middle.

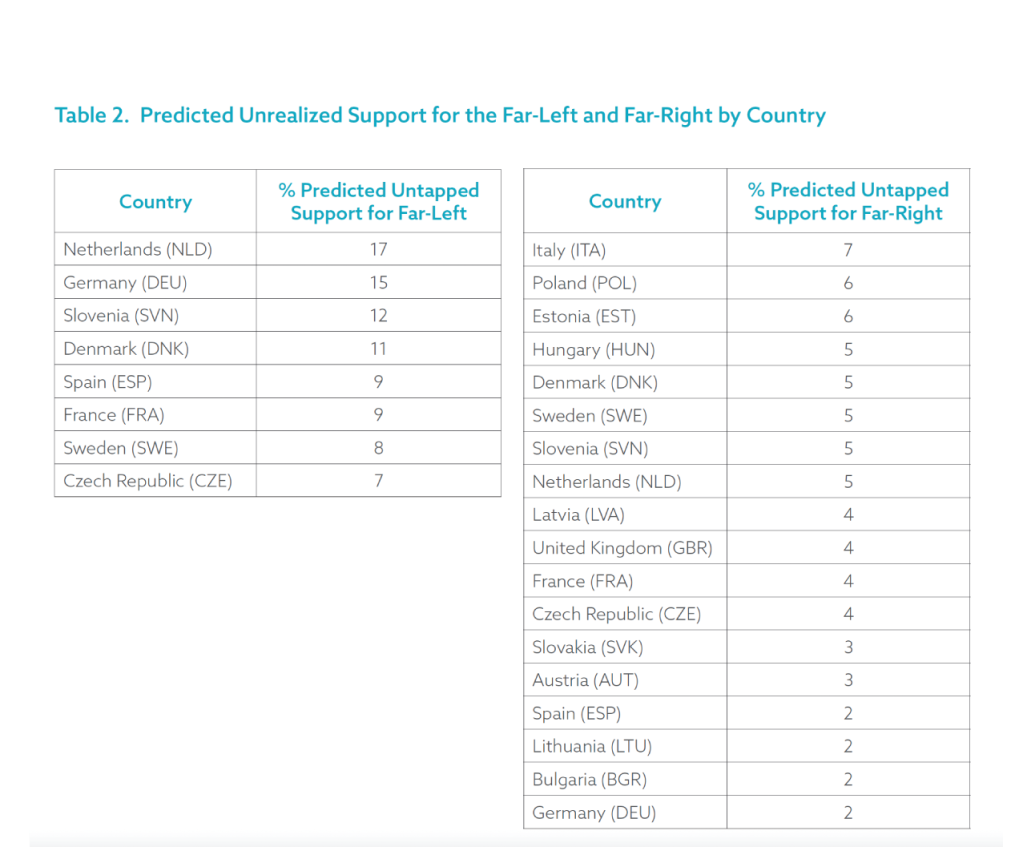

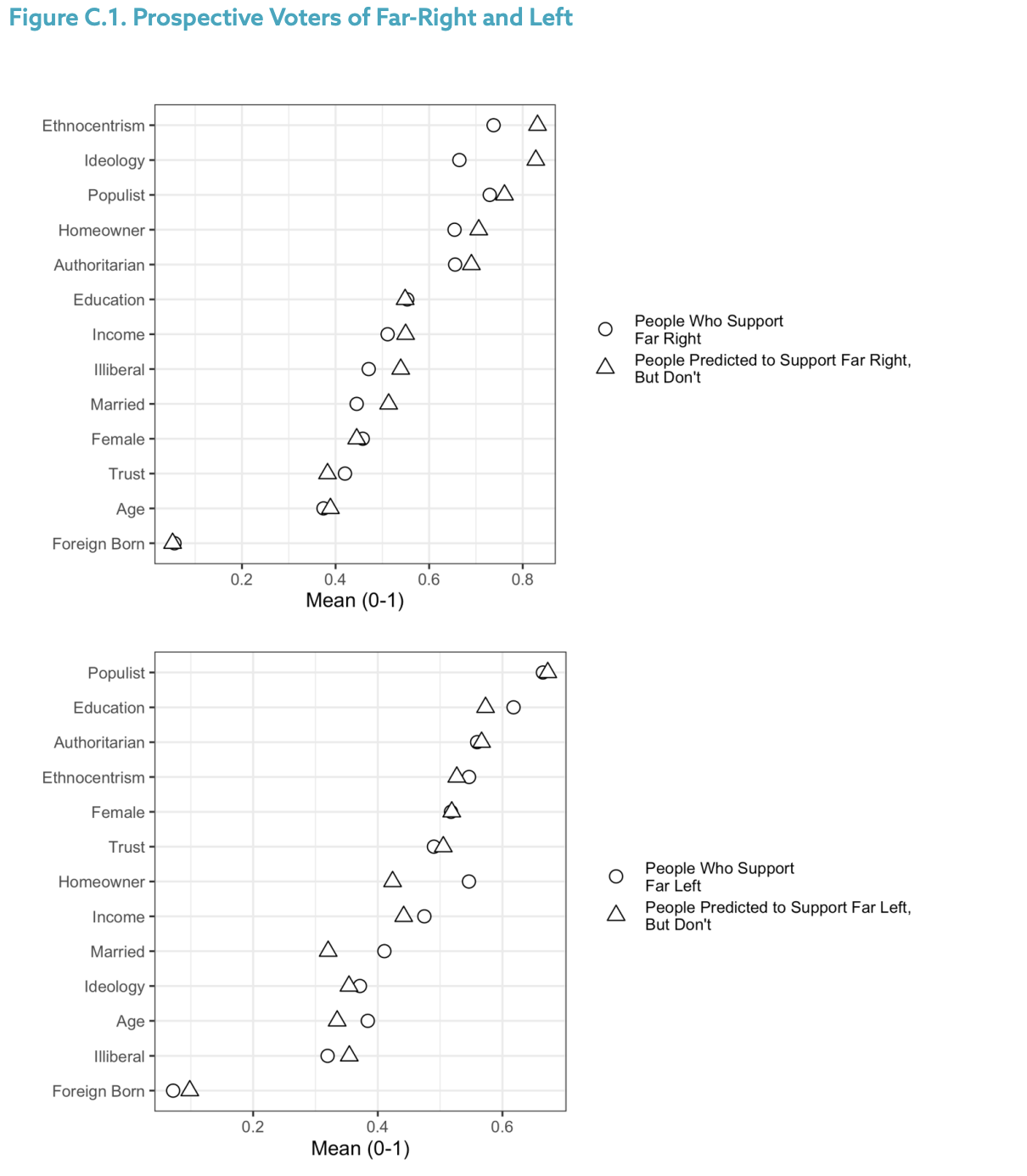

To identify the unrealized potential of far-right — and far-left — parties in different countries, we created a model that uses demographic and attitudinal data to predict which current mainstream center-left and center-right party supporters would be most likely to defect to the fringe in the future. To do this, we examine the average demographic and attitudinal characteristics of far-left and far-right supporters, as well as those of current center-left and center-right supporters who our model predicted would support the far-left or far-right. (Further details are in Appendix C1.) First, looking at the far-right, we find that there remains a substantial share of the population, about 4 percent of our sample, in countries with far-right parties who are more ethnocentric, ideologically conservative, authoritarian, and illiberal than current far-right supporters but who do not currently support the far-right. Similarly, with the far-left, we find that there is a substantial share of people, about 10 percent of our sample in countries with far-left parties, who are young, single, low-income, and are relatively illiberal, and who could be persuaded to back the far-left. These findings suggest that Europe’s fringe parties have not yet peaked. They still have room to grow.

With this room to grow, the question is where this growth is likely to take place. Using the same models of support for the far-right and far-left across all of Europe, we estimate the percentage of the population in each country that is predicted to support the far-right and far-left but currently do not. Our models suggest that there is potential for modest growth in support for the far-right across most of Europe (Table 2), with estimates ranging from 2 percent of the population in Germany to 7 percent of the population in Italy. There is potentially room for more growth in support for the far-left, with estimates ranging from 7 percent of the population in the Czech Republic to 17 percent in the Netherlands.

Addressing Immigration

Supporters of the far-right (and many supporters of the far-left) hold exaggerated estimates of the foreign-born in their respective countries. It is impossible to disentangle whether citizens support fringe parties because of these perceptions or whether it is the influence of fringe party leaders that has inflated people’s impressions of demographic change. Either way, the correlation is clear, and this perception is among the strongest of the attitudinal variables we examine. Despite divergent levels of ethnocentrism between far-left and far-right supporters, there are both far-left and far-right supporters who espouse anti-immigration sentiment. While alarmism about immigration is fundamental to the far-right’s ideology, some far-left leaders advocate for restricting immigration as part of a broader platform against globalization, capitalism, and neoliberalism. Europe-wide, while far-right supporters largely believed that immigration levels should be “reduced a lot,” far-left supporters’ views merely approached the European mean. Mitigating these concerns about demographic change is central to diminishing the appeal of the fringe parties, but pro-immigration advocates have historically struggled to alleviate them.

To this end, we used an original approach that leverages the rhetoric of the far-right to justify more immigration, rather than less. In each country we randomly assigned one third of the survey’s respondents to a control group and asked another third to read the news article reprinted below. The language and Eurostat-provided data is accurate and adapted for each participant’s current country of residence. Here is the British edition:

Birth Rates Declining in the UK;

Experts Argue More Immigration Needed From Outside Europe

According to demographers, birth rates in the United Kingdom are significantly below the level needed to maintain the native British population. If conditions remain unchanged, the average citizen in the United Kingdom will be 46 years old by 2040. This trend is expected to place pressure on the economy as the share of retirees expands and rural areas become less populated.

Even though over 3 million immigrants have already entered the UK over the last five years, government advisers have argued that to maintain current population levels, the United Kingdom will need to accept significantly more immigrants from countries outside of Europe with higher birth rates, such as Muslim-majority and African countries.

The first paragraph primes participants with information about the fragility of native British demography — the kind of so-called demographic cliff data employed by far-right elements to fearmonger about what has been termed the Grand Replacement, a fringe conspiracy theory contending that elites are progressively replacing white European populations with Muslim and African peoples, thanks to immigration and low native birth rates. To clarify the detrimental effect of population loss, the paragraph emphasizes the economic consequences of the current imbalance.

On this premise, the second paragraph affirms the interest of the government in maintaining current population levels and reports on expert recommendations to admit more immigrants. A significant amount of European migration originates from inside the European Union. In numerous countries, more than half of all immigrants enter via the EU’s free mobility arrangement. To make this a particularly hard test of demographic justifications for liberalizing immigration policy, we note that immigrants may come from Muslim-majority and African countries, which more xenophobic Europeans find less familiar and more threatening than fellow Europeans.

After viewing the news article—adapted for each of the 19 countries—all respondents were asked whether immigration to their respective country should be kept at its present level, increased, or decreased. Because the question of immigration levels is connected to emotionally charged group-centric concerns, they have been shown to be among the most difficult political views to alter.18 In Europe, the question of immigration is often even more sensitive than in the United States, because countries do not have the same legacy of welcoming newcomers. Moreover, unlike American identity, European concepts of the nation are more directly rooted in an indigenous people, less apt to “evolve” with the composition of their population. And in some cases, their populations and territory are quite small, and more sensitive to the influx of foreigners.

Still, invoking the need to maintain population levels was sufficient to modestly nudge average attitudes toward increasing immigration — by 0.10 points (on a 1-5 scale) across the 19 European countries surveyed, and by 0.14 points among the Western European countries that have historically experienced higher levels of immigration. In the Czech Republic, Denmark, Spain, and the United Kingdom, the two paragraphs produced better than a 0.20 point shift in attitudes toward increasing immigration. When we limit the results exclusively to those respondents who passed an attention check that ensures they are carefully reading the survey questions, the effects are amplified. Among these respondents, the paragraphs moved average attitudes toward increasing immigration by over 0.13 points across all 19 countries, and by just under 0.20 points across the Western European countries—0.30 points in Spain and 0.30 points in Denmark, whose population of under 6 million people has enacted some of Europe’s strongest anti-immigrant legislation in the years following the 2015 influx of migrants and asylum seekers.

Of course, our prime about demographic population loss is insulated from nationalist rhetoric that would otherwise contend that immigrants do not extend the nation’s survival but are precisely the elements that threaten it. To test how resilient our original priming is against such rhetoric, we exposed the final third of the sample to a corollary paragraph appended immediately after the first two. Invoking the specific words of far-right Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, the corollary— again adapted for each country, but here reproduced for the United Kingdom— reads:

Some worry that this trend could eventually cause the UK’s culture and way of life to disappear as native Britons become a minority. One politician recently said: “In all of Europe there are fewer and fewer children, and the elites’ answer is more migration. But population replacement is a reality that cannot be denied. Elites are introducing foreign elements into our society and diluting it so that our nationality will disappear.”

This is where Western and Eastern Europe diverge. Western European respondents were resilient to the nativist rejoinder, and the average effect of the full three-paragraph intervention was to nudge attitudes 0.14 points toward increasing immigration. However, in Eastern European countries, the effect drops to 0.03 points and loses its statistical significance, demonstrating the appeal of nativism to Eastern European respondents. The average effect across the 19 countries drops only slightly, to about a 0.08 point shift toward increasing immigration, and remains statistically significant. While the shift in Spain and the United Kingdom is unaffected by the nativist rejoinder, the effect shrinks substantially in the Czech Republic and Denmark—where far-right parties have been more successful. Filtering on the attention check amplifies this divergence. Western Europeans who pass the check are more persuaded, while no effect is detected among Eastern Europeans who pass the check.

The durability of the Western European results suggests the power of this unlikely reorientation of national survival rhetoric. The intervention is most effective among women; people between 35 and 49 years old; respondents who place themselves on the ideological left or ideological center; respondents with low or moderate levels of formal education; and respondents with low and middle incomes. The so-called national survival intervention was also significantly more effective in shifting the attitudes of people who expressed less concern about the coronavirus pandemic, which was receding but ongoing in Europe at the time of the survey. This suggests that the pandemic was exerting downward pressure on our findings, which would have been amplified under more normal circumstances.

Coronavirus Context

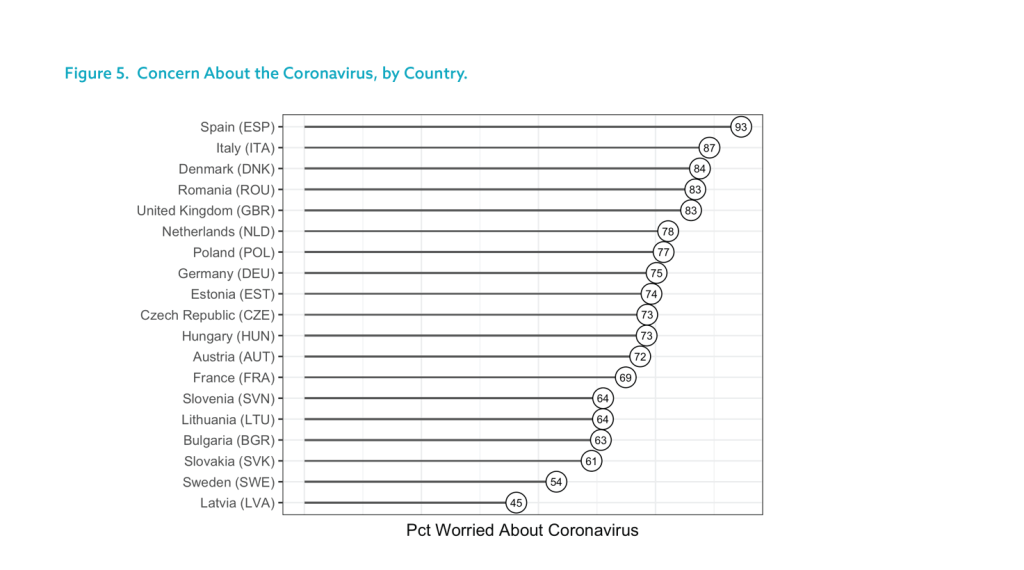

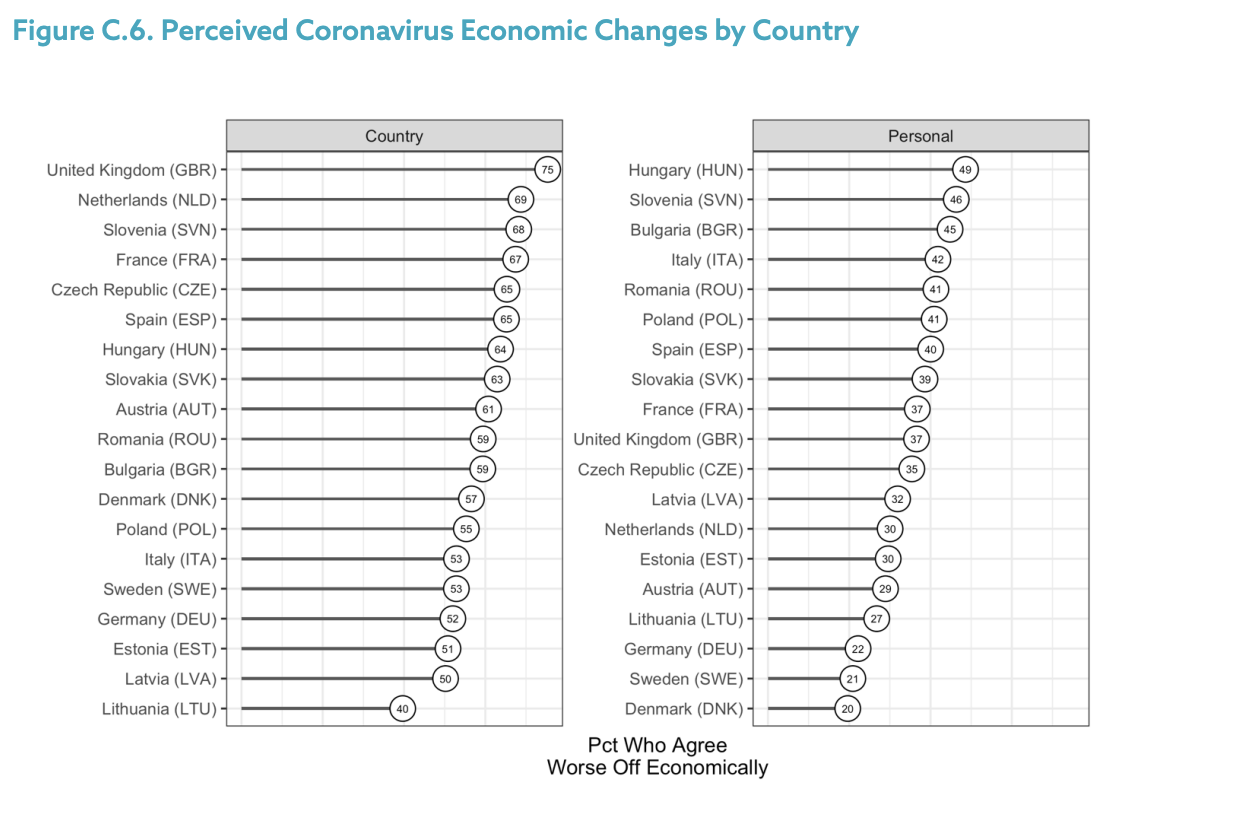

Our survey was conducted amidst the 2020 coronavirus pandemic — in August and September 2020, when infection rates had dipped to lower levels in Europe, but before the availability of a vaccine. As we observed in the experimental results, concern about the spread of disease and its effect on people’s health and livelihood clearly has an effect on public attitudes. However, concern is also highly variable. The share of the population that is worried about coronavirus (Figure 5) was highest in Spain and Italy, where concern was nearly universal. There are also high levels of worry in Denmark, Romania, and the United Kingdom. In Latvia, meanwhile, not even half of the population reported feeling worried.

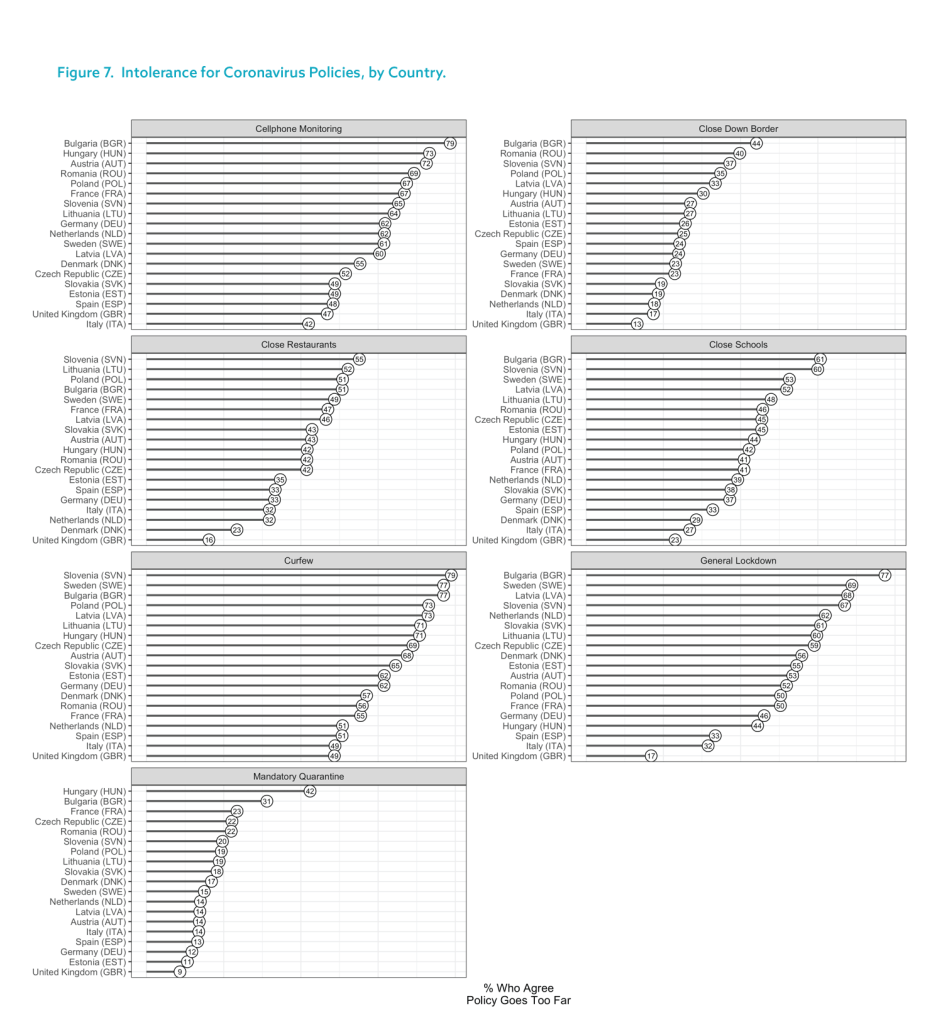

Those populations predisposed to worry are also those open to more aggressive policies that mitigate the spread of disease (Figure 7). The British, Italians, Spanish, and Danes are the most supportive of proposals for mobile phone monitoring, curfews, mandatory quarantining, general lockdowns, and the closure of restaurants, borders, and schools. Despite their elevated levels of worry, Romanians were often resistant to these measures. Europewide, the most popular policy proposals are the imposition of mandatory quarantining for people who test positive for coronavirus and the closure of international borders. The least popular measures are the imposition of curfews, general lockdowns, and the use of mobile phone monitoring for contact tracing purposes. The British stood out as especially willing to entertain such measures in the interest of public health and safety.

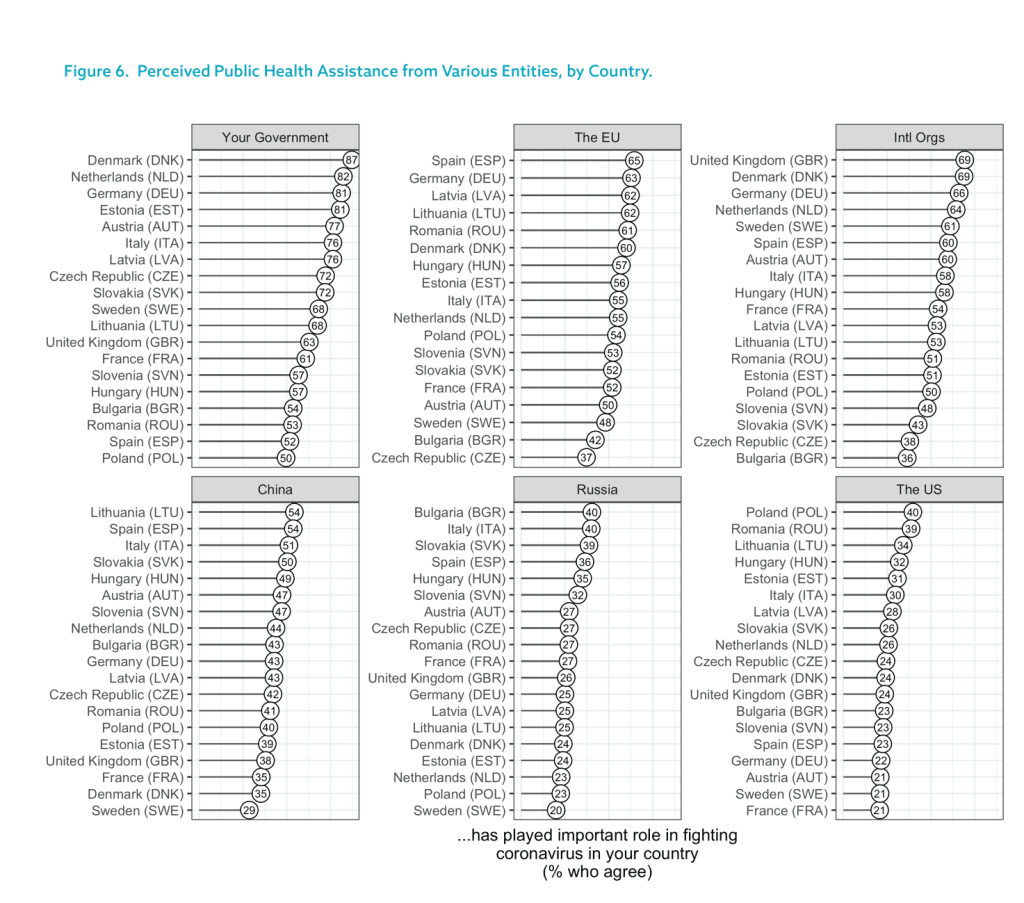

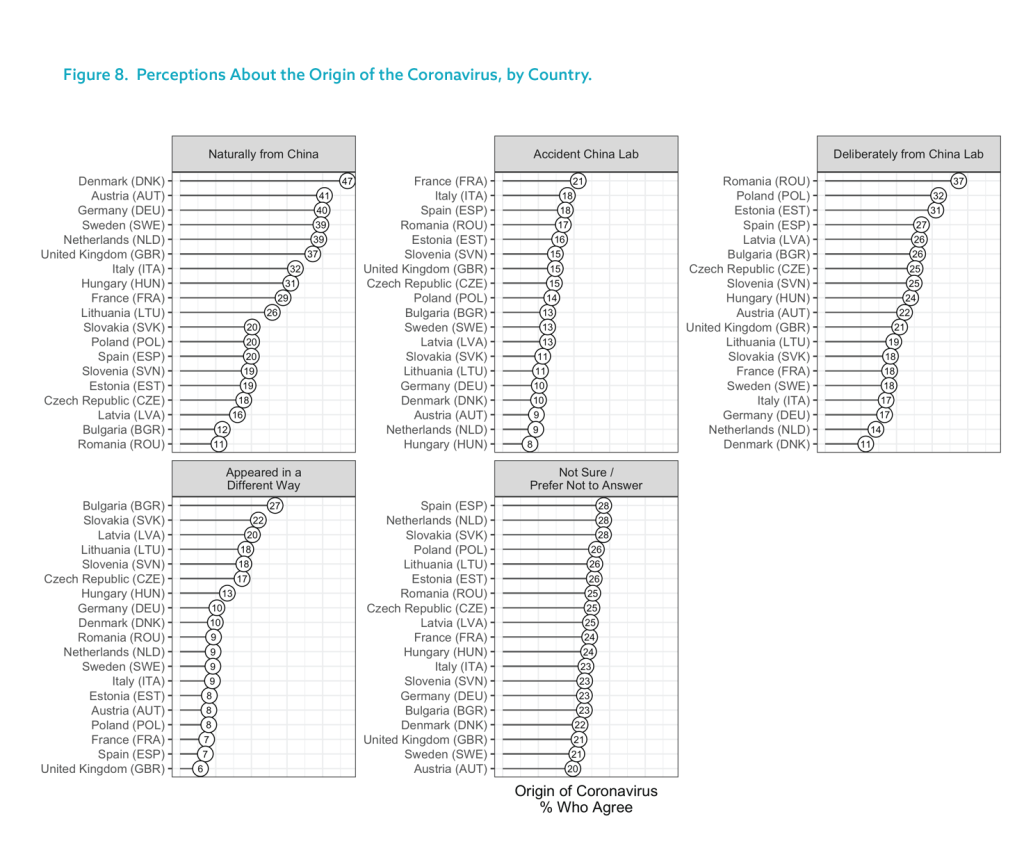

Respondents were asked for their impressions about the extent to which external actors were combatting coronavirus in their respective countries (Figure 6). While national governments were perceived as having the most important role, respondents also acknowledged moderate contributions by the European Union and international organizations. Respondents viewed the United States and Russia as playing the least important role — outdone even by China, a country that many respondents accuse of deliberately developing the virus. Indeed, when asked about the origins of the COVID-19 virus at the center of the pandemic (Figure 8), nearly as many respondents believe it was developed in a Chinese laboratory as believe it developed through natural causes. The theory related to a Chinese laboratory was most popular in Eastern European countries and also in Spain, while belief in the virus’ natural origins was most popular in Western European countries.

Conclusion

This study’s most striking conclusion is that illiberalism unites both the far-left and far-right fringes of European citizens. To the extent that populism is a coherent phenomenon, it appears to be driven by illiberal responses to a sense of transformative social change — neoliberalism for the far-left, demographic change for the far-right, each an expression of globalization. Of course, far-left and far-right responses diverge, as the former seeks more authoritarian measures against immigration and minorities, while the latter seeks a revolution against capitalism. Correspondingly, attitudinal explanations for fringe party support also diverge. While far-left support is correlated with low levels of ethnocentrism and faith in public institutions, inversely, far-right support is correlated with severe ethnocentrism, inflated estimates of demographic change, and distrust of public institutions. Importantly, all attitudinal factors explain party preferences much better than demographic attributes.

Based on these findings and statistical models, we predict the amount and location of untapped potential support for fringe parties in Europe — countries with a substantial population of people who fit the profile of fringe party supporters, but do not yet support them. The results demonstrate that these movements still have some room for growth. In particular, far-right parties appear poised for growth in a number of mostly Eastern countries where they already hold a significant amount of power (Estonia, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Slovenia) and Western European countries with far-right parties that have yet to access power (Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden). Our estimates project mild gains for the far-right, and potentially substantial gains for some far-left parties, if their mainstream counterparts are unable to retain support.

To better retain support, our research finds counterintuitive promise in the logic of nationalism. Using an experimental design, we conclude that an effective way to persuade more Europeans to support future immigration is to connect foreigners’ admission to the maintenance of the nation — the very nation that nativists claim immigrants threaten. Doing so substantially and statistically significantly increases the share of Europeans who support admitting more immigrants. Our findings appear to be pressurized by the coronavirus pandemic, which made those Europeans most worried about the spread of disease less inclined to change their views about immigration and more inclined to grant greater powers to governments.

Appendix A: Recent Election Results and Electoral Preferences

Appendix B: Methods

We use OLS regression with heteroskedastic-robust standard errors clustered at the county level to estimate favorability (0=unfavorable, 1=favorable where 1 is 5 or greater on 0 to 10 favorability scale) and voting for far-left and far-right (1=supported far-left/far-right party in last election, 0=voted other). All models include country-level fixed effects and survey weights. All covariates are re-scaled between 0-1 scale so that coefficients can all be interpreted as the change in probability of supporting or voting for far-left or far-right parties moving each covariate from its sample minimum to maximum values.

Scale Construction

Illiberalism

An additive scale was constructed of the following items which were reverse coded so that higher levels of agreement (strongly agree) were coded as 4 and lower levels of agreement (strongly disagree) as 1. The entire scale was then rescaled between 0 and 1, where 0 indicates the lowest observed value and 1 the highest.

- Before making decisions, the government of [Country] should consult religious leaders

- It is better to have a strong, unelected leader than a weak leader who is elected by the people

- The government of [Country] should comply with the interests of the majority, even if this comes at the expense of ethnic and religious minority groups’ civil rights

- The government of [Country] should be empowered to prosecute members of the news media who make offensive or unpatriotic statements

- The [C1_insert] of [Country] should be empowered to remove judges when their decisions go against the national interest

Perceptions of Demographic Change

A scale was constructed by subtracting perceived foreign-born diversity 25 years ago from perceived diversity today, generating a measure of perceived demographic change that was rescaled between 0 and 1, where 0 indicates the lowest observed value and 1 the highest.

- Of all the people living in [Country] today, what percentage do you think were born outside of the country?

- How about 25 years ago? Out of all the people living in [Country] 25 years ago, what percentage do you think were born outside of the country?

Trust

Trust is an additive index of the following items ranging from don’t trust at all (1) to strongly trust (4). The scale was rescaled between 0 and 1, where 0 indicates the lowest observed value and 1 the highest.

- How much trust you have in … to usually make the right decisions? : The [Country]’s Parliament

- How much trust you have in … to usually make the right decisions? : The European Parliament

- How much trust you have in … to usually make the right decisions? : The European Commission

- How much trust you have in … to usually make the right decisions? : Local government officials

Populism

Populist attitudes are an additive index of the following items each ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4) and was rescaled between 0 and 1, where 0 indicates the lowest observed value and 1 the highest.

- The government of [Country] is effectively run by a few big interests looking out for themselves

- Overall, you can trust politicians to do what is right

- The people should have the final say on the most important political issues by voting on them directly in referenda

- The politicians in [Country] government ought to follow the will of the people

Contact

The contact scale is an additive scale made up of the following two items which was rescaled to range between 0 and 1, where 0 indicates the lowest observed value and 1 the highest.

- How often, if at all, do you have contact with people born outside of [Country]?

- In the last year, have you invited someone born in another country to your home to share a meal?

Deprivation Measures

To construct the power, economic, and social deprivation measures we subtracted perceptions of current power, economic status, and social status from perceptions of past power, economic, and social status, creating a continuous scale ranging from those least deprived (much more powerful, greater economic status, or greater social status today compared to past) to the most deprived (far less powerful, lower economic status, and lower social status today compared to past). The original scale ranges between -10 and 10 though the measures were rescaled between 0 and 1, where 0 indicates the lowest observed value and 1 the highest, for inclusion in regression models.

- Power Status Today: Using the 0 to 10 scale below, how much power do people like you have in [Country] today? Power Status Past. And still using the 0 to 10 scale below, how much power did people like you have in [Country] 25 years ago?

- Economic Status: Using the 0 to 10 scale below, how financially well off do you consider yourself compared to other people in [Country] today? Economic Status Past: And still using the 0 to 10 scale below, how financially well off were people like you compared to other people in [Country] 25 years ago?

- Social Status: Below is a diagram which represents how central and important you are to your society. […] Thinking about this, where do you think you are in [Country] today? Social Status Past: On the same diagram, where were people like you placed in [Country] 25 years ago?

Authoritarianism

Authoritarian attitudes is an additive index of the following items each ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4) and was rescaled between 0 and 1, where 0 indicates the lowest observed value and 1 the highest.

- Young people should be taught to respect authority

- Censorship of films and magazines is necessary to uphold moral standards

- People who break the law should be given stiffer sentences

- The law should be obeyed, even if a specific law is wrong

Ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism is an additive index of the following items each ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4) and was rescaled between 0 and 1, where 0 indicates the lowest observed value and 1 the highest.

- Ethnic and religious diversity is good for [Country] (reverse code)

- Ethnic and religious minorities should adapt to the customs and traditions of [Country]

- There are limits to how many people of different ethnic and religious backgrounds can come to any country before that country starts losing its culture

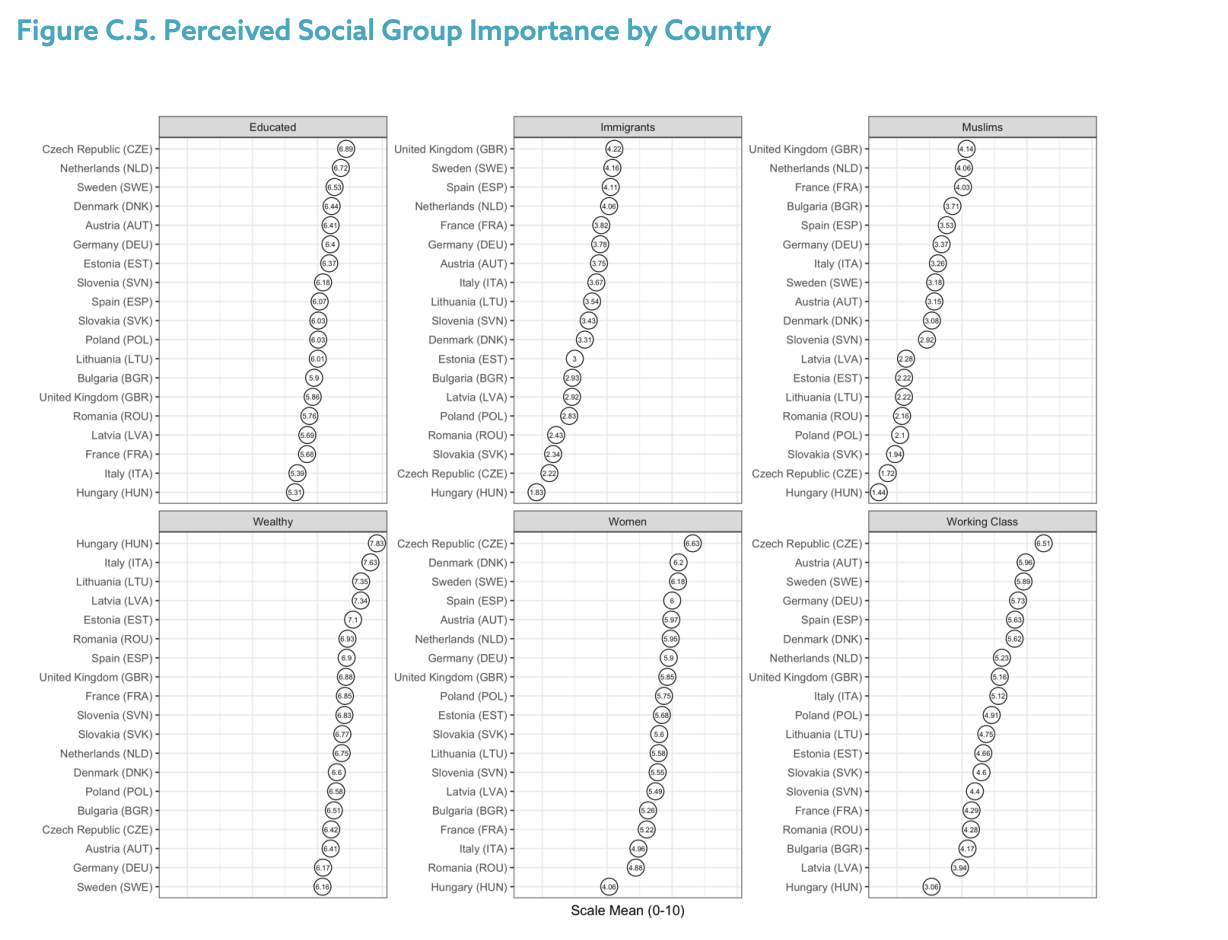

Appendix C: Additional Results

Endnotes

- Mudde, C. (2004). The Populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563; Bonikowsky and Gidron.

- See Golder, M. (2016). Far Right Parties in Europe, Annual Review of Political Science Vol. 19: 477-497; Mudde C. 1996. The war of words defining the extreme right party family. West European Politics. 19: 225–48;

- e.g. Betz H.G. (1994). Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe. New York: St. Martin’s; Halikiopoulou, D., & Vasilopoulou, S. (2018). Breaching the Social Contract: Crises of Democratic Representation and Patterns of Extreme Right Party Support. Government and Opposition, 53(1), 26–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/gov.2015.43; Vasilopoulou, S., Halikiopoulou, D., & Exadaktylos, T. (2014). Greece in Crisis: Austerity, Populism and the Politics of Blame. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(2), 388–402; Gyárfášová, O., & Jupskås, A. R. (2012). The appeal of populism. In H. Baldersheim & J. Bátora (Eds.), The Governance of Small States in Turbulent Times (1st ed., pp. 157–185). Verlag Barbara Budrich; Adler, D., & Ansell, B. (2020). Housing and populism. West European Politics, 43(2), 344–365; Akkerman, T. (2003). Populism and Democracy: Challenge or Pathology? Acta Politica, 38(2); Algan, Y., Guriev, S., Papaioannou, E., & Passari, E. (2017). The European Trust Crisis and the Rise of Populism. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 309–400; de Lange, S. L. (2007). A New Winning Formula?: The Programmatic Appeal of the Radical Right. Party Politics, 13(4), 411–435;

- e.g. Ivarsflaten E. 2008. What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Re-examining grievance mobilization models in seven successful cases. Comparative Political Studies. 41: 3–23; Gidron, N., & Hall, P. A. (2017). The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right. The British Journal of Sociology, 68(S1), S57–S84; Bustikova, L. (2014). Revenge of the Radical Right. Comparative Political Studies, 47(12), 1738–1765. Cutts, D., Ford, R., & Goodwin, M. J. (2011). Anti-immigrant, politically disaffected or still racist after all? Examining the attitudinal drivers of extreme right support in Britain in the 2009 European elections. European Journal of Political Research, 50(3), 418–440; Ford, R., Goodwin, M. J., & Cutts, D. (2012). Strategic Eurosceptics and polite xenophobes: Support for the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) in the 2009 European Parliament elections. European Journal of Political Research, 51(2), 204–234; Harteveld, E., Schaper, J., Lange, S. L. D., & Brug, W. V. D. (2018). Blaming Brussels? The Impact of (News about) the Refugee Crisis on Attitudes towards the EU and National Politics. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(1), 157–177;

- e.g. Bustikova, L. (2009). The Extreme Right in Eastern Europe: EU Accession and the Quality of Governance. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 17(2), 223–239; Chesterley, N., & Roberti, P. (2018). Populism and institutional capture. European Journal of Political Economy, 53, 1–12;

- e.g. Dancygier, R.M. 2010. Immigration and Conflict in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press; Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259– 1277; Golder, M. 2003. Explaining variation in the electoral success of extreme right parties in Western Europe. Comparative Political Studies. 36: 432–66.

- One notable exception is Halikiopoulou, D., Nanou, K., & Vasilopoulou, S. (2012). The paradox of nationalism: The common denominator of radical right and radical left euroscepticism. European Journal of Political Research, 51(4), 504–539; De Vries, C. E., & Edwards, E. E. (2009). Taking Europe To Its Extremes: Extremist Parties and Public Euroscepticism. Party Politics, 15(1), 5–28.

- One notable exception is the work of Noam Gidron and Peter Hall: Gidron, N., & Hall, P. A. (2020). Populism as a Problem of Social Integration. Comparative Political Studies, 53(7), 1027–1059; Gidron, N., & Hall, P. A. (2017). The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right. The British Journal of Sociology, 68(S1), S57–S84.

- Givens, T. (2005). Voting Radical Right in Western Europe. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; Norris P. 2005. Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Market. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; Mudde, C. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press; Art D. 2011. Inside the Radical Right: The Development of Anti-Immigrant Parties in Western Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press; Also see Wagner, M. (2012). When do parties emphasise extreme positions? How strategic incentives for policy differentiation influence issue importance. European Journal of Political Research, 51(1), 64–88; Bischof, D., & IRI | Europe’s Path Back From The Fringe 46 Wagner, M. (2019). Do Voters Polarize When Radical Parties Enter Parliament? American Journal of Political Science, 63(4), 888–904.

- e.g. Gest, J. (2016). The New Minority: White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality. New York: Oxford University Press; Gidron, N., & Hall, P. A. (2017). The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right. The British Journal of Sociology, 68(S1), S57–S84.

- Separately, we also ask respondents the extent to which economic conditions in their municipality have changed in the last decade.

- Sides, J, and Citrin J. (2007). “European Opinion about Immigration: The Role of Identities, Interests, and Information.” British Journal of Political Science 37:477–504.

- See Gest, J. Reny, T. and Mayer, J. (2018). “Roots of the Radical Right: Nostalgic Deprivation in the United States and Britain.” Comparative Political Studies. 51(13). p. 1694-1719.

- See Bustikova, L., & Guasti, P. (2017). The Illiberal Turn or Swerve in Central Europe? Politics and Governance, 5(4), 166–176; however, also see Rooduijn, M., & Akkerman, T. (2017). Flank attacks: Populism and left-right radicalism in Western Europe. Party Politics, 23(3), 193–204.

- Betz H.G. (1994). Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe. New York: St. Martin’s; Taggart P. 2000. Populism. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press;

- Voting is based on self-reporting by respondents. We measure party “favor” on a 0-to-10 scale for all major parties across the full sample from the 19 countries. Unlike vote shares, which are limited to people who report voting, we measure favorability among non-voters as well. When we dichotomize between those who “favor” or “support” different parties, we only include respondents who rate the respective party 6 or higher on the 10-point scale independent of whether or not they report voting for it. This “favor” metric thereby evaluates general views of parties, separate from voting behavior.

- In Eastern Europe, several of fringe parties have already achieved a majority. By definition, that means that the individual-level background characteristics will be less predictive of support.

- Kustov, A. Laaker, D. and Reller, C. (2019) “The Stability of Immigration Attitudes: Evidence and Implications,” forthcoming in the Journal of Politics.