- Introduction

- Background: Understanding Information Manipulation

- Identifying, Responding to and Building Resilience against Information Manipulation

- Step 1: Identify

- Step 2: Respond

- Reporting

- Reporting to Elections Management Bodies, Government Agencies and Law Enforcement

- Reporting to Social Media Platforms

- User Reporting

- Other Ways to Engage With Platforms

- Engage with Platform Teams

- Participate in Collaborative Cross-Industry Efforts

- Strategic Communications

- Inclusive Communications

- Fact-Checking

- Social Media Platform Initiatives to Increase Access to Credible Information

- YouTube

- Strategic Silence

- Step 3: Build Resistance

- Appendix A: Case Studies

- Appendix B: Additional Information on Social Media Platforms

- Appendix C: Additional Resources

- Footnotes

Introduction

Over the past few years, the International Republican Institute (IRI), the National Democratic Institute (NDI) and the Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO) have observed efforts to undermine election-related information integrity in every corner of the world. Without concerted efforts to identify, respond to, and build long-term resilience to election-related information manipulation, attacks on information integrity threaten to delegitimize elections globally, reduce faith in elected governments, polarize societies and weaken democracies writ large.

Dealing with information manipulation around an election is a new and unfamiliar phenomenon for many countries. Civil society actors, journalists, governments, election management bodies and other democratic actors often end up scrambling to respond in the lead-up to an election. To address this challenge, IRI, NDI and SIO have joined forces to create this playbook, intended to help leapfrog the first six months of the electoral preparation process. The playbook lays out the basics of the problem and the core elements of a response, and points to trusted resources for those looking to do a deeper dive into a particular type of intervention or threat.

We hope this playbook will enable you and everyone dedicated to defending democracy to push back against efforts that undermine free and fair political competition. Since information manipulation is an ongoing challenge, this playbook will also be useful outside of an election cycle.

The Playbook Approach

The playbook approach consists of how to (1) identify ongoing information manipulation campaigns; (2) develop real-time and short-term responses; and (3) build long-term resilience to information manipulation. While we outline three distinct steps in this playbook, the process for combating information manipulation is circular, with each step overlapping and reinforcing the others. Planning timelines will vary based on context, but—if at all possible—we encourage proactive rather than reactive planning to effectively counter electoral information manipulation. The playbook’s three-part strategy can help you develop rapid and real-time responses, as well as establish long-term and sustainable approaches to building resilience in order to maintain the integrity of elections and strengthen democratic processes.

Background: Understanding Information Manipulation

This section lays out the components of information manipulation and defines commonly used terms.

What is Information Manipulation?

Information manipulation is a set of tactics involving the collection and dissemination of information in order to influence or disrupt democratic decision-making. While information manipulation can co-opt traditional information channels—such as television broadcasting, print or radio—we focus on the digital aspects of information manipulation. Here, we explore how information manipulation campaigns co-opt different digital vectors, are led by different actors, and use a variety of tactics to distribute different kinds of content.

Threat Actors

In most election environments, a number of different actors will likely engage in information manipulation. To make things more complicated, while some of those actors may operate independently, others may operate in coordination, be at crosspurposes, or benefit from the general chaos and lack of trust in the information environment. Different actors have different goals for engaging in information manipulation. A political campaign will focus on winning an election; the influence industry and commercial public relations firms want to make money; a foreign adversary might try to influence the election outcome, advance national interests, or sow chaos; or an extremist group might focus on advancing their political cause. Here, we have outlined common threat actors involved in information manipulation campaigns. Though this list is not exhaustive, it provides a starting point for thinking about the relevant actors in your own country’s context.

- Political parties and campaigns use information manipulation to discredit the opposition, use false amplification to reach a wider audience or suggest that they have more public support than they do, or manipulate political discourse in a way that serves their campaign agenda. It is important to note that political campaigns can make use of information manipulation both outside of and during election cycles.

- Hate and other extremist groups use information manipulation to advance their social or political agenda, often by fomenting hate and political polarization; silencing, intimidating or otherwise disenfranchising target groups; and inciting violence. Their goals can include turning the majority electorate against a particular group, increasing support for extremist policies, and/or suppressing political participation.

- Foreign governments use information manipulation as a tool of statecraft and geopolitics. Information manipulation might be used to influence the outcome of an election in a strategically important country, advance the interests of the government or shape public perception of the state abroad. Information manipulation can be both covert (e.g., through the use of fake accounts) or overt (e.g., through statebacked media).

- Domestic governments use information manipulation to influence public attitudes and suppress the political participation or expression of certain users, such as activists, journalists or political opponents. Like foreign states, governments use both overt and covert information manipulation to achieve political goals, including the repression of human rights. Domestic governments can also more readily enact censorship as a form of information manipulation.

- Commercial actors, composed of social media platforms, public relations companies or strategic communication firms, use information manipulation as part of a business model, working with other actors to spread disinformation for profit. The influence industry often works with political campaigns, governments or foreign states to support their particular goals.

- Non-independent media with a specific political agenda or economic interest, or who are backed by a government or other political actor, may use information manipulation to influence public attitudes in line with the goals of their backers.

Determining who is behind information manipulation can be difficult, especially when the goals of different actors might overlap. For example, a foreign state actor might amplify content produced by domestic hate groups or conspiracy theorists. At the same time, there are market incentives for producing mis/ disinformation where generating virality can also generate income for users who create appealing content and place advertisements on their pages.

There are many ways to categorize the kinds of threat actors involved in information manipulation campaigns. The DFRLab’s Dichotomies of Disinformation1 can help you think about the kinds of actors and motivations behind information manipulation in more detail.

Content

Information manipulation makes use of a variety of content to influence, disrupt or distort the information ecosystem. This content can be used to influence public attitudes or beliefs, persuade individuals to act or behave in a certain way—such as suppressing the vote of a particular group of people—or incite hate and violence. Many types of content can be involved in information manipulation. Here we outline a few key terms used throughout the report and by other researchers, activists and practitioners who study and combat information manipulation.

- Misinformation is false, inaccurate or misleading information, regardless of the intent to deceive. ● Disinformation is the deliberate creation, distribution and/ or amplification of false, inaccurate or misleading information intended to deceive.

- Malinformation takes truthful or factual information and weaponizes it for persuasion. For example, this might include content that was released as part of a hack-and-leak operation, where private messages are shared publicly with the goal of undermining an adversary.

- Propaganda is information designed to promote a political goal, action or outcome. Propaganda often involves disinformation, but can also make use of facts, stolen information or half-truths to sway individuals. It often makes emotional appeals, rather than focusing on rational thoughts or arguments. Propaganda can be pushed by other actors, but in this report, we focus specifically on state-sponsored propaganda.

- Hate speech is the use of discriminatory language with reference to a person or group on the basis of identity, including an individual’s religion, ethnicity, nationality, ability, gender or sexual orientation. Hate speech is often a part of broader information manipulation efforts. It is particularly present in election contexts where the goal of the information manipulation is to polarize political discourse and/or suppress the political participation of a particular group.

There are many additional ways to categorize the types of content involved in information manipulation. For additional resources, see Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making, commissioned by the Council of Europe and produced in cooperation with First Draft and Harvard University’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy.2

Tactics

Information manipulation makes use of a variety of tactics to spread, amplify or target messages to different audiences on social media. Many of these tactics exploit the features of digital and social networking technologies to spread different kinds of content. While media manipulation is not new, digital tactics can change the scope, scale and precision of information manipulation in various ways. Here, we provide definitions for some of the key tactics that researchers, journalists, activists and platform companies have identified.

- AI-generated technology is used in information manipulation to create fake profiles or content. Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies, like Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN), use machine learning “neural networks” to create images or videos that look like real people but are completely fake. This includes “deepfake” videos, which use AI technologies to create realistic-looking videos that are entirely false.

- Manipulated visual content is used in information manipulation to photoshop images or edit videos. This can involve so-called “cheap fakes,” which do not use AI-generated technologies, but rather alter videos with a lower level of technical sophistication.

- Search engine manipulation uses tools from digital advertising—such as keyword placement—to exploit gaps in search results. These strategies attempt to place disinformation at the top of search engine queries, so that individuals looking for accurate information are more likely to come across disinformation.

- Fake websites are used to create the substance behind an influence manipulation campaign by creating “fake news” websites or content farms that publish large amounts of false, misleading or inaccurate stories, sometimes counterfeiting real news organizations.

- Trolling is the bullying or harassing of individuals to provoke an emotional reaction in the target. While anyone can be trolled online, certain communities experience trolling differently— and often more severely. This includes women, individuals with diverse gender identities, racial or ethnic minorities, or people of color.

- Computational propaganda involves the use of “bots” and other forms of automated technologies to amplify propaganda and other harmful content online. Bots are pieces of code designed to mimic human behavior by liking, sharing, retweeting or even commenting on posts. They can be used to falsely amplify certain kinds of content or accounts online.

- Fake or “sock puppet” accounts involve accounts, run by real people, who generate inorganic engagement. Like bots, fake or sock puppet accounts can like, share, retweet or comment on posts to falsely amplify certain kinds of content or accounts online. But rather than being automated, fake or sock puppet accounts are run by real people.

- Hack-and-leak operations involve hacking into private or sensitive information sources and strategically leaking information to the public in order to undermine the trust or integrity of a person or idea.

- Account takeovers involve hacking into the accounts of real people in order to impersonate them or spread mis/ disinformation to large audiences.

- Advertising and microtargeting involve using online advertising platforms to collect data about users and targeting them with persuasive messaging.

- Censorship involves blocking, redirecting or throttling access to certain kinds of information online.

Many types of tactics can be used to manipulate the digital information ecosystem. These tactics will depend on the platform being used, the skillset of those involved and the unique country context where information manipulation is taking place. For further information about the kinds of tactics used in information manipulation campaigns, see the USAID Disinformation Primer.3

Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior and Information Operations

Social media platforms are trying to take more steps to combat information manipulation on their platforms. When they look for information manipulation, they use terms like Facebook’s “Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour” or Twitter’s “information operations.” Although the terms for information manipulation and their tactics differ across platforms, social media platforms are increasingly taking action against networks of fake accounts that spread disinformation, incite violence or undermine the integrity of elections. One core component of platform definitions around information manipulation is the use of inauthentic or sock puppet accounts that pretend to be someone they are not—like a foreign state actor pretending to be a citizen of another country. Since 2018, Twitter and Facebook have released more data about information manipulation on their platforms in their company blogs or on Twitter’s Information Operation Transparency Center.4 You can also find links to resources that can help you identify coordinated information manipulation campaigns in the Step 1: Identify section of this report. However, it is important to note that the definitions used by platforms to take down information manipulation have limitations. For example, when networks of real users share misleading information about an election, it can be much harder for platforms to take action against authentic users rather than inauthentic accounts. This is why it is important to additionally respond and build resilience to information manipulation through fact-checking, media literacy and the establishment of collaborative networks so that real users are less susceptible to sharing harmful, inaccurate or misleading information. You can read more about these strategies in the Step 2: Respond and Step 3: Build Resiliency sections of this report.

Vectors

The information ecosystem has dramatically changed over the past three decades. The internet and social media in particular have created an environment in which information manipulation is massively scalable, very cheap and easy to experiment with. While popular social media platforms— such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube—are often highlighted as vectors for information manipulation, these activities also occur on other social media platforms like Reddit, Pinterest, Instagram, TikTok, Tumblr and WeChat. They also occur across encrypted and nonencrypted messaging platforms like LINE, Telegram, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Signal or Viber. (For more information on conducting ethical investigations in closed environments, see the Step 2: Respond section.) Some information manipulation might target internet search providers, like Google, Yahoo or Bing. Others might target niche communities of users, like gamers, through platforms such as Twitch, Xbox Live, or PlayStation Online. As the major social media platforms have increased their efforts to set limits around the spread of harmful content, new social media platforms have been created. Some of those platforms are focused on creating unmoderated environments, and others have put in place moderation policies that explicitly facilitate the speech of one ideology over another, often with a focus on niche or extremist political views.

Information manipulation almost always occurs both online and offline: television, radio, print, academia and other aspects of the information ecosystem can be involved. For instance, journalists or the media may amplify content created as part of an information manipulation campaign if that content has been shared by an important political figure, or if it is particularly sensational and likely to attract audiences. A sophisticated actor that engages in information manipulation may capture prominent news outlets or give grants to research entities to produce analysis that supports their objectives.

Emerging Challenges for Information Manipulation

Information manipulation is constantly adapting to changes in the media ecosystem. As social media companies become better at detecting and removing information manipulation from their platforms, threat actors have also learned to modify their strategies, tools and tactics. While early researchers were concerned about the use of political bots to amplify mis/ disinformation on social media platforms, today the distinction between automated bot accounts and human curated content is becoming less clear. The rise of various commercial actors offering disinformation as a service also makes it harder for social media companies to detect information manipulation and take action against them, as trolls-for-hire are paid to pollute the information sphere. At the same time, the distinction between foreign information operations and domestic extremism or terrorism is becoming less clear, as foreign meddling has increasingly co-opted domestic narratives to amplify pre-existing racial, gender or political divisions.

While platforms have policies for removing coordinated inauthentic behaviour (CIB), as of August 2021, there are no clear guidelines for managing coordinated authentic behaviour. When mainstream and globally ubiquitous platforms like Facebook, Twitter, TikTok or YouTube take action against content and accounts, sometimes these voices reappear on other platforms or private channels that lack the same standards for removing content or accounts that spread mis/disinformation or hate speech, or that incite violence. And some platforms, like WhatsApp or Signal, encrypt personal and group messages, making it much harder to detect information operations and counter the spread of mis/disinformation and other forms of harmful information. While encryption can protect the privacy and security of online activists and human rights defenders, malign actors have leveraged the security of these platforms to enhance the spread of harmful or misleading information online.

At the same time, not everyone experiences information manipulation the same way. Journalists, political activists and members of the political opposition are frequently the targets of smear campaigns and harassment designed to undermine their credibility and legitimacy as professionals. These campaigns are often more severe for women, minorities, or people of color, who face greater levels of harassment, online threats and sexualization. Minority or marginalized populations are also often targets of online violence that can have real-world implications for their security and safety, as online speech can affect offline political violence.

Finally, technology itself is constantly evolving, and new innovations are creating new opportunities for information manipulation. Artificial Intelligence is creating numerous opportunities for online deception: automated bot accounts can use machine learning algorithms (like GPT-3) to sound more human; generative adversarial networks (GANs) can be used to create fake profile pictures that look like real people, or other forms of synthetic media like “deepfake” videos. For example, deepfake videos are being used to falsely depict women in pornography, which can have damaging and lasting impacts on their mental health and career prospects. Innovations in data surveillance also introduce new challenges for information manipulation as it becomes much easier to target specific communities or individuals with persuasive messaging. Data about user likes and interests can be used to predict the values and behaviors of individuals or groups, and commercial actors are already building models to target communities of people with (de) mobilization messages. The data that can be used in information manipulation will only grow as the Internet of Things introduces more data points about users, from wearable devices to smart cars, appliances and sensors. We must evolve our responses to keep pace with these innovations and to build resilience to future information manipulation.

Identifying, Responding to and Building Resilience against Information Manipulation

Once you understand the basic aspects of information manipulation, the next critical step is to develop an understanding and skillset to identify future risks and ongoing operations in your own country’s context. Identifying ongoing campaigns, as well as future risks, is one of the most difficult steps, because malign actors will often obscure their identity and create barriers for technical attribution. To help you with this process, this section provides a few key strategies. We have also compiled a list of useful and accessible resources to assist you throughout the process of identification.

Step 1: Identify

Mapping the Information Environment

The first step to identifying information manipulation is to map the information environment in order to identify the unique vulnerabilities for your election. You should conduct a risk assessment that identifies the various threat actors who might launch an information manipulation campaign and the channels— including digital, broadcast, radio or print—that might be used as part of their efforts. You will also want to identify various partners you will work with to combat threats that arise, such as social media company policy representatives, government officials, law enforcement agencies or other civil society organizations (CSOs). This section provides an overview of key questions to answer in order to map the information environment.

- What is the media and information landscape? The first step of mapping the information environment is to understand your current media landscape. Where do people get their political information? Where is information manipulation likely to take place? Here, you should consider traditional media entities, like television broadcasters, newspapers and radio stations, and assess the transparency of media ownership, correction policies, and the professional standards that media adhere to. You should also consider digital media, such as social media platforms, encrypted chat applications or web forums. Familiarize yourself with the policies of platforms where you suspect information operations could take place by reviewing their terms of service agreements and community guidelines as well as other country-specific measures that might have been announced in company blogs. You should also make yourself familiar with existing fact-checking initiatives and the role of other online influencers in shaping political discourse for certain communities of users.

- Where are online audiences, and which communities of users are more vulnerable to information manipulation or negative implications from these campaigns? Information manipulation affects users differently, and women, people of color, and people with diverse gender identities and sexual orientation experience information manipulation more severely than others.5 The second step of mapping the information environment is to understand your audiences and the groups of people who might be marginalized, suppressed or deeply affected by ongoing information manipulation efforts. This involves looking closely at small and local communities in your country’s context.

- Who are the likely threat actors? The third step of mapping the information environment is to identify the various threat actors and understand their motivations for conducting information manipulation. Understanding who is, or could be, behind information manipulation will help you respond and build resilience to future operations. Ask yourself: Who are the main threat actors—are they domestic actors, foreign states or both? What could be the motivations behind these campaigns— are they for political disruption or economic gain? See the Background section for more information on threat actors and their motivations for conducting information manipulation.

- Who are partners you can work with to combat information manipulation? The fourth step of mapping the information environment is to identify partners who can assist you with combating information manipulation. Here, you should consider identifying relevant government and non-government partners, such as election management bodies, who may be able to assist in responding to ongoing information manipulation campaigns. Journalists and other CSOs in your country can work with you to fact-check or provide counter-messaging to information manipulation. You should also identify contacts at social media platforms who you can work with to take content or accounts off social media. It is important to note that not every partner will be relevant for every context. What is important is to identify who will bring skills, resources or capacity to assist you in responding and building resilience to information manipulation. To help you identify relevant partners, you can explore the Countering Disinformation Guide Intervention Database.6

- What are the relevant regulations you should be aware of in your research and for reporting? Each country will have different laws or regulations relating to elections, campaigns and online speech. The fifth step of mapping the information environment involves developing an understanding of your country’s relevant legal and regulatory landscape around issues related to the electoral information environment. Knowing these rules will prepare you to better work with government agencies in responding or building resilience to information manipulation, or to protect yourself and your colleagues and organization when deciding how best to respond. For example, some governments might have regulations that prevent campaigning three days before an election. There might also be rules or regulations in place about foreign ad purchases. Knowing these relevant regulations can help you report unlawful content to regulators and election management bodies, as well as to social media platforms for removal.

Tip: Don’t Forget Regional and Local Platforms

In this playbook we list the major global social media platforms, but be aware that there are many other regional and local platforms as well. Cross-platform sharing of manipulated content is common, and you will observe information shared on one platform being shared across others. We advise that you do a deep dive on your local information ecosystem and observe which social media platforms are widely used and how they relate to each other. In addition to your own observation, a useful resource to assist in mapping the information landscape is the We Are Social7 reports on social media use by country. The Global Cyber Troops inventory8 also provides an overview of information manipulation by country and the various vectors used in information manipulation campaigns.

Identifying Common Information Manipulation Narratives

After understanding the information environment you will be working in, you can start to think about the kinds of narratives or themes different actors might use in their information manipulation campaigns. We have outlined common narratives used in information campaigns during elections to assist you with identification.

- Polarizing and divisive content is sometimes used in information manipulation campaigns to inflame political, racial, religious, cultural or gender divides. These narratives often focus on pre-existing divisions within society, and use identity-based narratives to sow discord and discontent among the electorate.

- Delegitimization narratives spread content that undermines the integrity of the electoral process. This could be false claims about the security of voting machines, errors in ballot casting or tabulation, or other alleged irregularities. These narratives are designed to sow distrust in the processes that support elections. Delegitimization narratives can also focus on discrediting certain politicians or candidates, election officials, or civic entities.

- Political suppression narratives are used to discourage certain groups of people from participating in politics. These suppression strategies target democratic processes; this could include spreading disinformation about how and where to vote, or suggesting that certain communities of individuals are not allowed to vote or that there is violence at polling stations. They could also include narratives that pressure voters to attend, or not attend, political rallies or events, or that encourage voter fraud.

- Hate, harassment and violence is another form of suppression that uses harassment, slander or threats of violence to discourage certain users or communities from expressing their thoughts or opinions online or engaging in debates necessary for a well-functioning democracy. Hate, harassment and violence create a culture of fear and can stifle political expression online.

- Premature election results or claims of victory are sometimes made on social media to erode trust in the outcome of the election. They are often made before ballot counting has been completed, and are especially likely if a political race is close and contentious.

Many kinds of narratives can emerge during an election, and many of them will be specific to your country’s context. It is important to think about the kinds of narratives that might be used as part of information manipulation campaigns so that you can be more prepared to respond with counter-messaging or build resilience to narratives before they spread. The Computational Propaganda Project’s Global Cyber Troops Inventory9 describes other kinds of narratives or “communication strategies” that have been observed in information manipulation campaigns around the world.

Identifying Ongoing Information Manipulation Efforts

Once you have mapped the information environment and understand the different kinds of narratives actors might use to undermine election integrity, you should begin monitoring the ecosystem for ongoing campaigns. Threat actors will often try to conceal their identity or their campaigns in order to avoid detection. However, there are a number of resources and best practices available for identifying ongoing campaigns, which we have compiled for you. You should also consider these five key principles when conducting investigations into information manipulation.

- Context Matters. Every country and election will occur in a different media, cultural, social and economic environment. It is important to map your information ecosystem and the likely threats in order to focus on the relevant technologies and platforms that are prominently used in your country.

- Know Your Limits. Any research into information manipulation comes with limitations, and the data we collect about these kinds of campaigns are always imperfect. It is important to understand what you do and don’t know about information manipulation based on the data you are working with, and not jump to conclusions about the authenticity of online information. It can be just as damaging to the legitimacy of an election if information manipulation is misattributed.

- Behavior Over Content. When identifying information manipulation, it is important to look at patterns in behaviour of accounts, rather than looking at a single piece of content. Platforms are better able to respond to coordinated inauthentic behaviour, and identifying large networks of accounts in coordination to manipulate the online information environment will provide a stronger basis for taking down content and accounts.

- Do No Harm. The collection, storage and use of online data can have implications for personal privacy and security, and it is important that any information collected to monitor information manipulation is conducted in an ethical way. Online data can come with expectations of privacy, and thinking about consent, security and privacy is an important part of your job as an investigator. Data that is improperly stored or anonymized can have negative consequences for personal privacy or the security of users who are participating in politics online. Thus, it is important to take necessary steps to do no harm, and to protect and secure any data you’re working with.

- Zero Tolerance for Hate, Suppression and Violence. Hate or incitement to violence online can have real-world consequences not only for the integrity of elections, but for the security of citizens. These narratives do not always come from coordinated inauthentic accounts or as part of formalized information operations but might be shared by authentic or real users. However, any information that spreads hate, attempts to suppress political participation or speech, or incites violence should be immediately reported to the platforms and other relevant parties regardless of the source. More information on how to report content can be found in the Reporting section of Step 2: Respond.

Tip: Identifying Information Manipulation Offline

Keep in mind that information manipulation campaigns can occur offline as well as through online platforms; mainstream media (such as television, radio and newspaper) are common vectors for the spread of false information, and you should keep the above principles in mind when consuming information from offline sources as well. Be sure to verify the information that you hear or see before you share it with your trusted networks and members of your organization. Since mainstream media often has intentional biases, it can sometimes feature false information or “half-truths” (see Digital Literacy in the Step 3: Build Resilience section, page 44).

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) Tools for Identifying Information Manipulation

OSINT is the collection and analysis of information from public (open) sources. These resources can be used for tracking and identifying disinformation.

Bellingcat’s Online Investigation Toolkit: (Resource List) This easy-to-navigate Google Doc spreadsheet has different tabs for different tools for verifying information, such as image and video verification; social media content and accounts; phone numbers and closed messaging services; maps and location-based services; transport trackers; IP and website analysis; international companies; environment; tools for improving online security, privacy and data visualization; academic resources; and additional guidebooks.10

Data Journalism’s Verification Handbook for Disinformation and Media Manipulation: (Guide) This handbook helps you conduct OSINT research into social media accounts, bot-detection and image manipulation. It also provides resources for conducting investigations on the web and across platforms, as well as some tips and tools for attribution.11

The Beacon Project’s Media Monitoring Handbook: (Guide) This handbook helps you conduct datadriven analyses of disinformation narratives and their sources. The handbook is a good starting place for researchers interested in conducting media monitoring, but are not sure where to start, as well as those looking to ensure methodological best practices are being applied.12

CrowdTangle: (Tool) Facebook created CrowdTangle as a tool for identifying and monitoring trends on social media. The tool can track verified accounts, Pages and public Groups. The tool can also be used to monitor public accounts on Instagram and subreddit threads on the Reddit platform.13

You should review these resources, as well as additional tools in Appendix C on page 59, to determine what tools will be most useful to you and your organization for identifying information manipulation. Every campaign, organization and country context will be different and require a mix of tools, skills and partners, so developing an understanding of the tools that can help you identify and monitor ongoing campaigns will empower you to respond and build resilience.

Developing a Workflow

When tracking information manipulation, you will need to develop both short- and long-term monitoring strategies. When developing a workflow, you should consider:

- What are your goals or main objectives? Are you trying to reduce the impact of disinformation by fact-checking narratives? Or are you trying to build accountability around malign actors engaging in disinformation? Your goals will directly shape the scope of your monitoring, as well as the kinds of tools and partners you work with.

- What is the scope of your monitoring? Determining scope involves asking questions like:

- What is the internet penetration in your country, and will social media be a source of information during elections?

- What platforms are in scope for monitoring?

- What are the biggest threats to electoral integrity as it relates to disinformation?

- Who are the potential actors involved in information manipulation?

- What election-related themes are considered in-scope for your monitoring, what languages will you work in, and what issues will be outside the scope of your investigations?

- What tools will you use to assist you with identification and monitoring?

- When gathering data about influence manipulation across digital, print or broadcast media, how will data be collected, labeled and stored to make analysis and triage more accessible to you and your organization? The process of tracking and monitoring influence campaigns can take weeks or even months, and establishing a system that allows for collection over time will be critical to your success.

- Who will be responsible for monitoring the information ecosystem? How will they work and how will they be trained in order to have a consistent approach in identifying influence manipulation online?

- Are there certain time periods that will require you and your organization to ramp up monitoring activities, such as before an election or important political referendum?

For more resources on developing your workflow and thinking about the scope of your identification processes, see The European Union Guide for Civil Society on Monitoring Social Media During Elections. 14

Step 2: Respond

In this playbook, respond means reacting quickly to harmful election-related online activity. No matter how strong your defenses and emphasis on prevention might be, the reality is that those defending information integrity will always be playing catchup. As such, it is critical to additionally focus on identification and response in order to act swiftly and effectively against elections related information manipulation once it occurs. This chapter will cover responses including reporting to elections management bodies (EMBs), government agencies, law enforcement and social media platforms; strategic communications; fact-checking; and strategic silence.

study, which we have adapted to apply in a global context.15

Reporting

Information manipulation can be reported to elections management bodies (EMBs), government agencies, law enforcement, social media platforms, international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), fact-checking organizations, or organizations that represent the issue area or targeted community.

Each entity has different, and sometimes overlapping, roles in responding to information manipulation. Social media platforms can investigate and take steps to reduce the spread of misinformation and hate speech; governments and election commissions can create legal frameworks that limit the capacity of malign actors to engage in information manipulation, as well as launch information campaigns to share accurate information or debunk inaccurate information; fact-checking organizations can investigate the veracity of a claim and publicly debunk information manipulation; INGOs can work with local partners to ensure that concerns are taken seriously and that the capacity exists to address the situation; and organizations working on issue areas or with targeted communities can take steps to protect their communities and/or contribute to debunking efforts. The most effective efforts at reporting will likely involve engaging with a number of different partners on the basis of the local context and the specifics of the observed information manipulation. Note that responding to information manipulation is challenging for CSOs, EMBs or activists to approach alone; governments and technology companies must also step up to meet the challenges.

This section will help you develop an understanding of who plays what role, how to most effectively report information manipulation, and what you can expect once you report. It is important to understand that the guidance we provide may not work for every type of actor or information environment. When choosing the best tactics to follow, you need to consider your country’s context, the types of relationships or partners you already have, and your group’s mission, technical skills and expertise. For instance, not all groups will have the skills to conduct fact-checking or be able to report information manipulation to a government that is itself the source of the manipulation.

After going through the suggestions under Step 1: Identify, you should now consider the goals you would like to achieve by reporting information manipulation.

- Have the content taken down?

- Have users or pages banned?

- Prompt an investigation into coordinated inauthentic behavior or other violations of platform terms of service?

- Raise more attention and awareness on a specific event, trend or threat actor?

- Advocate for the government and social media platforms to take preemptive steps?

Once you consider the above questions, you will be better able to select which entities are most appropriate to report observed information manipulation to. You can report a similar issue or violation to several entities at once. We have grouped potential entities into three general categories:

Government

Check if your government, elections commission, or other cyber or information agencies have a mis/disinformation reporting system. If yes, you should consider reporting the violating content to them based on the consideration of a number of factors (see page 17).

Social Media Platforms

If the content or behavior is in violation of its hosted social media platform’s policies and terms, you can report the content to the relevant platform (see page 20).

Fact-Checkers

Consider sharing observed mis/ disinformation to fact-checking groups in your country or region (see page 32).

Reporting to Elections Management Bodies, Government Agencies and Law Enforcement

Most democratic countries have an Elections Management Body (EMB), Elections Commision, Elections Council or Elections Board16 that oversees implementation of the elections process, as well as government agencies and law enforcement that help uphold the elections-related regulations of any country.

Many EMBs do not have resources, structures or mechanisms in place to address election-related information manipulation or to protect themselves and the country’s elections from electoral information manipulation narratives. For those who do, very few have reporting mechanisms created for citizens to report elections-related information manipulation observed online.17 Furthermore, EMBs typically do not have the mandate to develop rigorous regulations around online campaigning nor the ability to enforce existing regulations. However, some EMBs have created disincentives to deter malign actors from taking part in electoral information manipulation by establishing campaigning codes of conduct and collaborating with social media platforms to regulate the behaviors of political parties and electoral candidates.

If you would like your EMB to explore solutions to disincentivize electoral information manipulation or create codes of conduct, you should directly advocate to your EMB. However, keep in mind that some EMBs are not independent bodies, so they may not be impartial in the structures and policies they enact or the actions they take against violators.

Available Resources for EMBs

The International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) has a number of resources and programs designed to help election commissions or management bodies effectively preempt and respond to information manipulation. If you work for an EMB or would like to learn more about the role that EMBs can play in responding to election-related information manipulation, see the Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening (CEPPS)18 Countering Disinformation Guide’s section19 on EMB approaches to countering disinformation.

In addition, some governments have created agencies to combat cyberattacks and other digital threats, some of which also function to safeguard electoral infrastructure, e.g., the United States’ Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and Indonesia’s National Cyber Encryption Agency (BSSN). Check to see if these types of agencies exist in your country and if they have set up citizen reporting mechanisms for elections-related information manipulation. If not, consider advocating to your elected government officials to put these in place. Review the CEPPS Countering Disinformation Guide’s Advocacy Toward Governments section20 for guidance and examples of how a CSO might advocate for its government to take action. It is important to be aware that authoritarian regimes have frequently cracked down on freedom of expression through newly developed cybersecurity agencies and legislation, using laws that identify opposition content as harmful “fake news or misinformation.”

If you or your organization work on elections campaigns, you need to carefully consider the legal frameworks, law enforcement, independent oversight bodies and other regulatory agencies that are or could be involved in the social media and larger information space. In certain cases, local or federal police agencies have teams specifically dedicated to enforcement of laws online. When they are honest brokers and can be relied upon, these law enforcement bodies form viable avenues for reporting and oversight of harmful campaigns. The judicial system can also play a role in governing the online space and can order measures to stop the dissemination of information manipulation online.

Independent oversight bodies might be an anti-corruption agency, a political finance oversight body, or a media oversight body. In the aforementioned legal and regulatory section21 of the CEPPS Countering Disinformation Guide, four kinds of regulatory approach are outlined in more detail that address both platforms and domestic actors, including measures to restrict online content and behaviors and promote transparency, equity and democratic information during campaigning and elections. These are all potential avenues that may present useful foci for policy advocacy, which are explored in more detail in the Guide, but should be carefully considered for each given national context. In other circumstances, particularly when the government does not respect democratic norms or is otherwise compromised, law enforcement or regulatory bodies can often play an actively harmful role, developing and applying laws that limit legitimate political speech in the name of combating information manipulation. It is more problematic and often counterproductive to report to those actors.

Countries that are generally free (see the Tools to Evaluate a Government’s Openness box) can create legal frameworks for reporting and responding to information manipulation in ways that protect and open the space for democratic discourse, while guarding against information manipulation. If a country is not free or partly free, you should proceed with caution in engaging with regulatory, judicial or other governmental organizations. At all levels of freedom, a country’s oversight bodies may be weak or ineffective in this domain, even in strong democracies. You should evaluate these bodies and survey regulations carefully, and potentially engage experts and review resources on their efficacy, trustworthiness and ambition.

If the rule of law or transparency of these bodies is low, other options (detailed below) should be considered. For additional guidance on reporting to law enforcement bodies, reference the CEPPS Countering Disinformation Guide’s section on Legal Frameworks and Enforcement. 25

As you seek to report election-related information manipulation to government agencies, elections commissions and other law enforcement bodies, some critical factors to consider are:

- Do you trust these agencies to act impartially?

- Does your government have the capacity and capability to take action on the reported content?

- Have there been actions taken by your government agency upon receiving reports of harmful online content leading to the takedown of those posts?

- Does your government regulate speech online or have laws against pre-elections smear campaigns, character attacks and information manipulation campaigns? Would those laws be used against opposition voices and political parties running for elections?

- What is the general political posture of the government? Is it generally open and democratic, or trending authoritarian?

- Does your government have a history of suppressing opposition voices and criticisms, especially ahead of elections?

- Are there government agencies that are themselves agents of information manipulation (both foreign and domestic)?

For a comprehensive list of examples of actions taken by governments around the world to defend against misinformation, including efforts ranging from legitimate attempts by democratic governments to ensure information integrity, to efforts by authoritarian regimes to censor speech they do not like, visit Poynter’s Guide to Anti-Misinformation Actions Around the World. 26

Tools to Evaluate A Government’s Openness

One measure of a government’s political posture is Freedom House’s Freedom in the World index,22 which measures whether a country is free, partly free or not free based on factors such as political rights and civil liberties. Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net Index23 surveys a government’s regulations related to the internet, alongside various other factors, as it assesses how open or closed a country’s national internet is, as well as the structure of the government agencies that regulate it and any relevant laws. It assigns each country a score that helps to classify the countries based on a number of factors, references and further details that should be reviewed as a component of an assessment of the information space and legal framework. These rankings are updated annually, but they need to be weighed in with the current situation in your country, for it may change quickly. Another measure is the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, 24 which has established a robust, multidimensional dataset that accounts for democracy’s complex systems and allows users to assess how a particular democracy has fared over time. These represent just three methods of gauging a country’s openness and respect for the rule of law, but understanding this component is a critical early step.

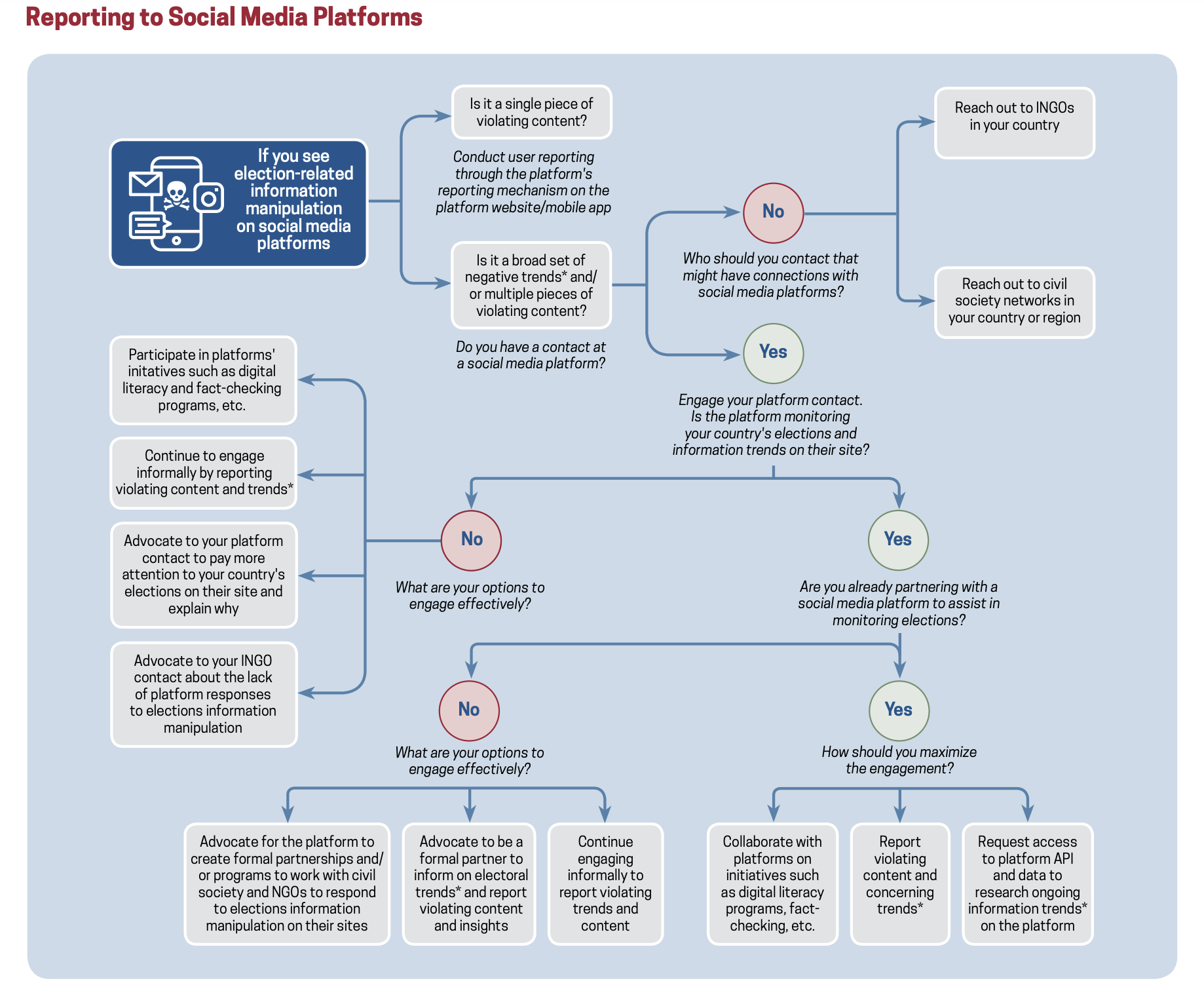

Reporting to Social Media Platforms

Social media platforms and online web hosts track and respond to information manipulation through a variety of mechanisms: user reporting, partnerships with civil society to identify local trends and risks, engagement with experts, back end in-house and external threat intelligence and digital forensics, cross-industry coordination, and engagement with governmental organizations. Depending on what type of organization you are and what you wish to communicate to the platforms, some of these options will be more relevant to you, and others less so.

The methods that platforms undertake to handle reporting about information manipulation, counter mis/disinformation, moderate content, and collaborate internally and externally vary widely and depend on where the company was founded, how long it has been operating, its finances, and its relationships with external stakeholders and the governments, among other considerations.

Tip: Don’t Make Reporting to Social Media Platforms Your Only Approach

Note that reporting violating content to social media platforms is a necessary but insufficient step. Platforms are unlikely to be responsive to user reporting in a timely manner, and it can take days or weeks to receive a response. Content that you find threatens electoral integrity might not be against a platform’s policy or community standards and could be left up. Often, platforms are also unprepared to handle a country’s electoral information environment on their sites or do not understand the local information space and threats. Hence, reporting to platforms should not be your only step and needs to be taken together with our other recommended actions. Social media platforms are rapidly evolving and require all those working on improving electoral information integrity to constantly monitor and, in some cases, advocate for product and policy changes and adjust their strategies in interacting with platforms.

User Reporting

User reporting is the most accessible way of raising concerns about specific pieces of content that violate the policies of the social media platform on which the content is being shared. User reporting is usually as simple as flagging a specific piece of content within the platform and giving an explanation as to why it is harmful. Note that user reports are usually reviewed by automated systems, human content moderators, and—in rare instances—other units within a company, on the basis of whether they violate existing company standards or policies. Those processes frequently suffer from a lack of societal or political context and knowledge of local languages. User reporting is not an effective way to draw attention to concerning trends or to a large-scale information manipulation campaign. However, it is effective at removing single pieces of content or social media accounts that clearly violate platform policies. For more details about each platforms’ community policies and guidelines for how reportable content is defined and other elections-specific platform interventions, refer to Appendix B on page 55.

The table below provides guidance on key platforms’ reporting processes. We listed the major social media platforms here due to their large number of users and global reach.

| Platform | How to Report |

|---|---|

| If you identify content and/or accounts on Facebook that you suspect are spreading harmful content ahead of elections, follow the links: Mark a Facebook Post as False News28 and How to Report Things29. Appeals can be referred to the Oversight Board. See the Facebook’s Oversight Board box on page 23. | |

| To submit reports of harmful mis/disinformation around elections, go to the Reducing the Spread of False Information on Instagram page.30 | |

| Google’s different products have individual terms of service that contain restrictions on hateful and misleading behavior and content, and Google’s processes for reporting mis/disinformation and other harmful content on its platform are also product specific. However, Google Search is most relevant in the case of this playbook. The tool for requesting removal of information from Google Search can be found on this page.31 | |

| Snapchat | To file a report of suspected elections-related mis/disinformation and other harmful content, use Snapchat’s in-app reporting feature32 or complete this form33 on its website. |

| TikTok | To report a video, comment, user, hashtag, etc., suspected of mis/disinformation and other harmful content, see detailed instructions on TikTok’s Report a Problem site.34 |

| To report Tweets, Lists and Direct Messages that you suspect are spreading harmful content about your country’s elections, follow the instructions here.35 Twitter defines harmful content under its Twitter Rules36 that can help you understand what is off limits and reportable under its definitions. | |

| YouTube | To report mis/disinformation and other harmful content that appears on YouTube through its videos, playlist, thumbnail, comment, channel, etc., use its in-platform mechanism that can be found on the report inappropriate content page.37 |

| To report harmful content to WhatsApp, follow the instructions here.38 Note that WhatsApp is a closed, encrypted messaging app, so monitoring content on this app is different from the other social media platforms listed above. |

Besides information presented in the table above, you can also find the Mozilla Foundation’s detailed instructions39 on in-app reporting. Be aware that the response time and investigative processes differ by platforms. Typically, after a platform user reports violating content through the platform’s online system, the review process flows as below:

- The platform’s automated system checks for obvious violations within the reported content— child pornography, known slurs, etc.—and removes violating posts.

- If the automated system is unable to provide definitive answers, then the reported violation is reviewed by content moderators, who may or may not be conversant in the local context and language.

- If content moderators find the posts to be in violation of the platform’s policies and community standards, the post is removed. In cases where it is not clear, the post is escalated to other teams within the company, e.g., the policy team, trust and safety team, etc.

- Depending on the severity and political impact of the issue, the specific post may be shared with the leadership of the company for more detailed considerations and review before a decision is made.

Facebook’s Oversight Board

Facebook created the Oversight Board to help it answer some of the most difficult questions around freedom of expression online, what to take down, what to leave up and why.40 The Oversight Board also provides an appeals process for people to challenge content decisions on Facebook or Instagram. If you already requested that Facebook or Instagram review one of its content decisions and you disagree with the final decision, you can appeal to the board. The process is detailed here.41 Not all submitted cases will be selected to undergo the appeals process, and the timeline of the process is fairly lengthy.

A Growing Trend: Information Manipulation in Closed Groups and Encrypted Messaging Applications

As platforms update their policies on information manipulation and increase and improve their efforts on content moderation and removal, malign actors are increasingly moving their information manipulation efforts to sites that are more difficult to monitor, specifically closed groups and encrypted messaging applications such as Facebook Groups, WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal, LINE and WeChat. Many of these apps are encrypted, and there is no effective way to monitor or proactively remove the spread of malign information. To counter harmful forms of content like disinformation, some apps have updated products and policies. For example, WhatsApp set up message forwarding limits to help “slow down the spread of rumors, viral messages and fake news.”42 Journalists and researchers have attempted to report from encrypted messaging apps by joining closed groups and setting up tip lines to encourage the public to send in content. However, these methods also pose many challenges for those who attempt to report violating content from encrypted messaging apps, particularly ethical challenges.43 Others from civil society have launched public awareness campaigns by sharing accurate information on WhatsApp. The effect of these types of campaigns remains to be seen, and results are difficult to measure. However, there have been some successful efforts to combat information manipulation on closed messaging platforms. In Taiwan, a collaboration between LINE and Cofacts allows for viral messages to be fact-checked by volunteers and debunked in chat without intrusions on privacy. In Spain, the fact-checking organization Maldita.es added an automated chatbot to its existing WhatsApp tipline in July 2020 to improve response time and build a database to track misinformation trends.44

If you’d like more information on how to monitor and report inside closed groups and messaging apps, refer to the European Journalism Centre’s Verification Handbook45 (specifically Chapter 7), First Draft’s Essential Guide on closed messaging apps and ads,46 and Brookings Institution’s policy brief on Countering Disinformation and Protecting Democratic Communication on Encrypted Messaging Applications.47

Other Ways to Engage With Platforms

Engage with Platform Teams

Most platforms have a variety of teams that can serve as touch points in the lead-up to, during and after elections. Those teams have a variety of incentive structures, roles, and interests, and are sometimes unaware of each other. Some may be locally based, while others are based in regional hubs or at company headquarters. The table below gives a broad overview of the roles related to elections and information manipulation that may exist in a given company. Note that identifying the right staff can be difficult. Some of these roles may be occupied by the same team or person, and newer platforms—even those with a large user base or impact on the information space—may have limited field presence, country representatives, or staff in these functions.

| Platform Teams | Roles |

|---|---|

| Public Policy and Government Relations | The public policy and government relations teams are usually responsible for engaging with regulatory agencies and other government bodies. Their predominant role is to ensure a favorable regulatory environment for the platform. Companies tend to have public policy representatives located in the capitals of countries that are significant markets. Public policy teams can be good entry points for those attempting to address information manipulation, but you should be aware that they have multiple competing priorities and incentives—particularly in instances where a national government is a bad actor in the information space—and thus may not always see dealing with information manipulation as consistent with their role. Some companies have community outreach/partnerships teams that specifically engage with civil society, advocacy groups and academia. |

| Content Policy / Human Rights | Established social media platforms who have faced significant issues relating to online harm will generally have a variety of teams working on mitigating that harm. Those teams will oversee the creation of policies that determine what is and is not allowed on the platform; develop and track specific policies related to human rights; and, often, develop partnerships with civil society to help inform the company’s approach to content and user behaviour. Some platforms have dedicated teams explicitly charged with ensuring election integrity. In some instances, those teams are permanently in place, but in other instances they may be established on a temporary basis to respond to a specific election of significance to the platform. |

| Content Moderators | Often contractors, not employees within the company, content moderators review user-reported content and decide if it aligns with the platforms’ policies and community standards. These contractors do not have the scope to change platforms’ standards. |

| Product | Product teams are responsible for launching platforms’ products and improving or changing products to prevent platform abuse and limit the spread of mis/disinformation (i.e., limiting forwarding of messages on WhatsApp, etc.). |

| Threat Intelligence | Researchers who conduct deep dive investigations into threats manifesting on a platform typically look at coordinated inauthentic or other types of behavior. |

If you are not already in touch with the platforms of relevance to your information space, most global social media companies have established partnerships with major INGOs or coalitions, such as the Design 4 Democracy Coalition,48 and other local or regional civil society networks, who can work with you to ensure you are communicating with the best point of contact within each company.

Tip: An Introduction to the Design 4 Democracy Coalition

The Design 4 Democracy Coalition (D4D), led by NDI, IRI, IFES and International IDEA, is an international group of democracy and human rights organizations, from a diverse collection of regions, political ideologies and backgrounds, that is committed to ensuring that the technology industry embraces democracy as a core design principle. By developing a forum for coordination and support within the democracy community on technology issues, and by creating an institutional channel for communication between the democracy community, civil society organizations and the tech industry, D4D is working to strengthen democracy in the digital age. The Coalition could serve as a useful resource for you; contact information is available on the D4D website. The D4D coalition also developed the TRACE Tool, a form that allows you to request access to training or tools provided by D4D’s technology partners, or to flag content or profile issues that need to be addressed through expedited means.49

Participate in Collaborative Cross-Industry Efforts

Most of the major online platforms have established processes and programs for partnering with civil society, independent media and academia on issues related to information manipulation. Those include mechanisms for gaining insight into local context and linguistic issues; formal partnerships with fact-checkers, journalists and civil society; and rapid escalation channels for select groups in crisis situations. Partners can preemptively provide contextual knowledge and flag issue areas and potential events that might be subject to information manipulation and cause real-life violence. This contextualization enables platforms to take immediate actions either by removing content or by taking proactive actions in modifying their products, policies and resources to prevent the platform’s facilitation of violence or anti-democratic behavior. This tactic is particularly effective for CSOs, journalists or activists who are victims of state-sponsored disinformation and harassment. These mechanisms are continuously adapted and may or may not be active in your country. The INGOs detailed under the D4D coalition above can help you navigate which programs are active in your country and how you can participate in those programs. You can find examples of successful initiatives in Step 3: Build Resiliency on page 40.

How social media companies approach information manipulation

Social media platforms typically prefer not to rely only on users reporting election-related mis/disinformation spreading on their platforms. According to the CEPPS Countering Disinformation guide,50 platforms have enacted policies, product interventions and enforcement measures to limit the spread of mis/disinformation. Most platforms also have some form of content moderation tools in place; you can find an inventory of these tools in the Toolkit for Civil Society and Moderation Inventory51 developed by Meedan.52

Platforms also limit the spread of election-related mis/ disinformation through the design and implementation of product features and technical or human interventions. This is highly dependent on the nature and functionality of specific platforms—traditional social media services, image and video sharing platforms, messaging applications, and search engines. Both Twitter and Facebook use automation53 for detecting certain types of mis/disinformation and enforcing content policies. The companies similarly employ technical tools to assist in the detection of inauthentic activity on their platforms and then publicly disclose their findings in periodic transparency reports that include data on account removals. You can find more details about different types of platforms’ efforts to limit the spread of mis/disinformation through product features and technical/human intervention in Appendix B on page 57 or in the CEPPS Countering Disinformation Guide’s topical section on platforms.54

Strategic Communications

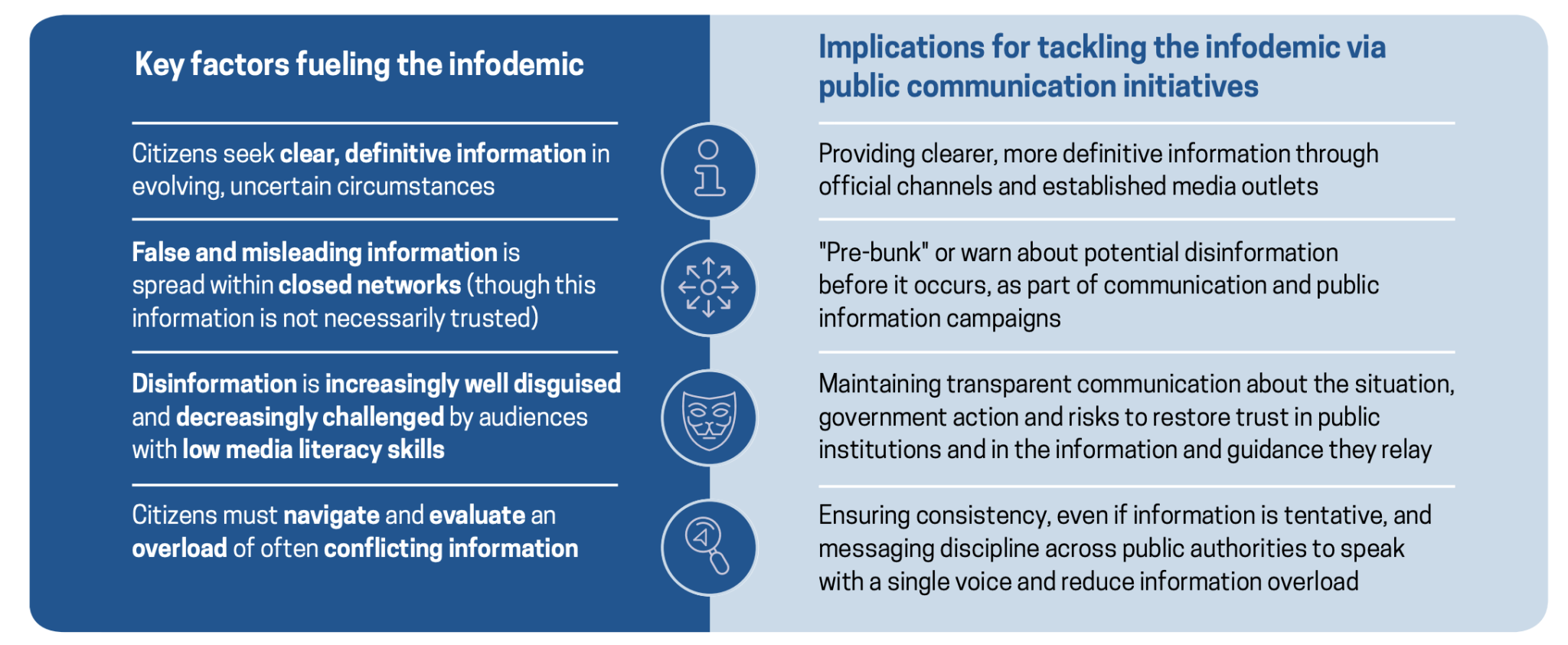

Communications in response to or in preparation for election-related information manipulation are typically broken down into two approaches: proactive and responsive.

- Proactive Communication: This approach aims to provide accurate, reliable, consistent and concise information regarding an election before any false narratives take hold, in an effort to create a trustworthy information space for citizens.

- Responsive Communication: This approach aims to counter false narratives once they have already gained traction, frequently involving directly identifying a false narrative and its objectives and responding to those inaccuracies with the truth (See the Fact-Checking section on page 32).

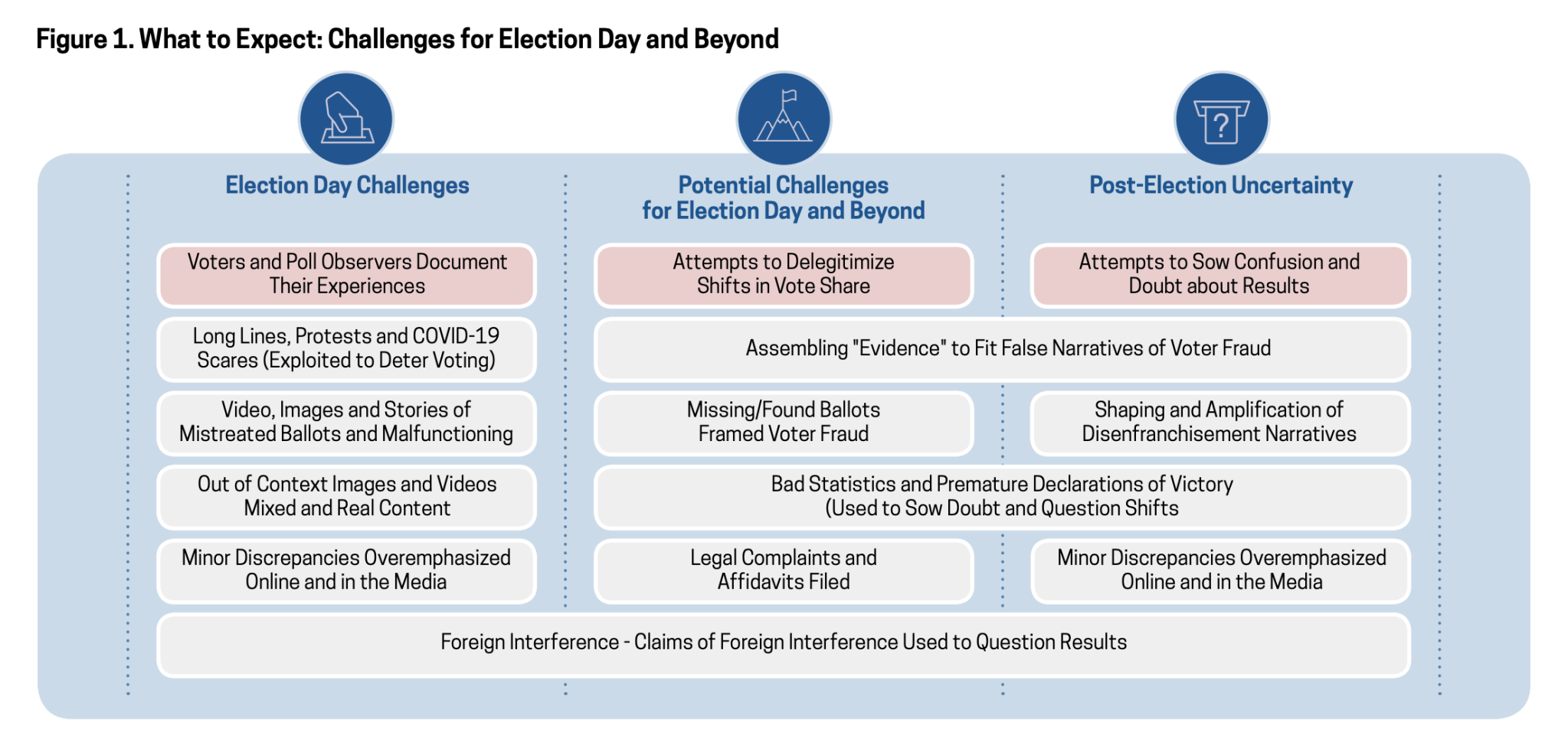

In advance of developing a strategic communications campaign, and before the election itself, take the time to consider common mis/disinformation and false narratives that inevitably emerge before, during and after elections so you will be prepared with positive, strategic communications well in advance. Common information manipulation campaigns include content that spreads confusion about voting procedures or technical processes, such as false voting times; content that may result in direct voter suppression, such as falsely reporting unsafe voting environments or inefficient or closed voting locations; and content that may delegitimize the election, such as narratives of widespread voter fraud, broken voting infrastructure or large-scale conspiracy theories.55

As you consider potential false narratives, begin planning for and agreeing to ready-made, well-crafted narratives and messaging that can be sustainably and quickly deployed throughout the election. Keep the best practices listed below in mind as you plan your strategic communication campaign to be sure messaging is clear from the outset and remains consistent and easy to understand throughout the election.

- Carefully research your audience and plan your campaign.

- Who is your audience(s)?

- What is the purpose of your message?

- What will resonate with your audience? How can you build inclusive messaging?

- Clearly define—and remain consistent with—your messaging goals.

- Create content. Concentrate on messaging that provides action steps for your audience. What are you asking them to do?

- Select the platforms and tactics to share your counternarrative. Consider accessibility and inclusivity in your platform choice; diversify communication channels to include those that are accessible in low-bandwidth areas; and use graphics, songs, theater plays or other innovative communication methods for those who may not be literate.

- Evaluate the impact. Continue to conduct research and monitor dialogue while keeping your original communication goals in mind. If conditions change, consider adapting your message to ensure your original communication goals are met.

While not all information manipulation necessitates a response (see the Strategic Silence section on page 38), there will be myriad false narratives that require attention as they gain public notice and influence. Any public communications regarding information manipulation—whether proactive or responsive in nature—should uphold truthfulness, openness, fairness and accuracy.56 To communicate about disinformation effectively, you should address:

- Timeliness. Speed is critical in countering information manipulation effectively; this means developing protocols for strategic communications that balance speed and accuracy, with clear guidelines on necessary approvals and communication steps. The longer disinformation goes unanswered, the more likely it will be effective.

- Messaging. All communications should be accurate, values-driven and compelling enough to compete (see Why Does Disinformation Go Viral?). Your messaging should be empathetic to concerns and follow “Easy Read” protocols described here.57 Additional guidance on developing a compelling messaging campaign can be found in the Co/Act Toolkit.58

- Avoid Accidental Amplification. If communications are directly countering a falsehood, the message must be framed in a way that ensures amplification of the truth rather than accidentally attracting more attention to the falsehood. Framing an unproven assertion between two truths better emphasizes accurate information rather than simply stating it.

- Partnering/Networks. Often other groups or networks have the same interests, and working together increases efficiency and strengthens the credibility of the information when shared by multiple sources. Consider partnering with existing networks or influencers—those with large numbers of followers who are able to reach broad groups of the population—to amplify your messages and build bridges with skeptical audiences (see here59 for an example of Finland’s use of influencers to spread true information about elections).

Many studies have indicated that the best predictor of whether people will believe a rumor is the number of times they are exposed to it.60 Using this same principle in promoting accurate news, communication campaigns should emphasize the repetition of a clear, focused message to most effectively spread the truth.61 Focus communications on sharing what the government is doing to organize and prepare for the elections, refuting mis/ disinformation, advancing the truth, and seeking to develop relationships with key audiences and constituencies.

Given the typically high volume of disinformation narratives surrounding elections, and the frequently limited capacity of democracy actors—including EMBs, CSOs, and even mass media sites—to dedicate resources to address this challenge, focus on countering the objectives of information manipulation campaigns, which are often aimed at exploiting existing divisions or changing public opinion about a political candidate or party, rather than countering individual narratives. EMBs, CSOs and other democracy actors should focus on proactive communication strategies, dedicating resources to promoting the truth rather than countering falsehoods.

In general, consider these steps as you plan your communications:

- Identify the key facts related to the election that are most critical to continually reaffirm as true—consider the who, what, where, when and how of elections—and use your messaging to establish ground truth facts as much as possible.

- Decide on the most trusted information channels and partners to help convey the message; provide clear messaging to them along with guidance to communicate the message.

- As you regularly share your message, continue to monitor media coverage, including social media, and establish a feedback loop for how your messages are picked up and responded to.

- Modify your message if conditions change (such as a shift on election day or outbreaks of violence) to demonstrate responsiveness, but be sure to maintain clear communications objectives and message consistency.

For more thorough guidance on communications aimed at countering information manipulation, refer to the resources below.

- The RESIST Counter Disinformation Toolkit Annex E: Strategic Communication (Tool) is a step-by-step guideline for deploying the FACT and OASIS models for effective strategic communication.63

- Countering Information Influence Activities: A Handbook for Communicators, (Guide) published by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, includes extensive guidance on how to choose the best communications response according to the information manipulation occurring.64

- Information Manipulation: A Challenge for Our Democracies (Guide) offers useful case studies and suggestions based on previous strategic communication campaigns.65

Why Does Disinformation Go Viral?