Introduction

Forced displacement is the result of complex and enduring challenges to democracy and peace around the world. At the end of 2019, 79.5 million people were displaced — which represents 1 percent of humanity and the highest number of displaced persons on record.1 The crises that drive the flight of millions of individuals show no sign of relenting, from protracted conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan and Syria to the debilitating humanitarian situation in Venezuela. Accommodating a sudden influx can strain the ability of host governments to deliver basic services and infrastructure and can enflame community tensions. But forced displacement can also be a catalyst for innovation, entrepreneurship and economic opportunity.2 For example, Venezuelan migration is projected to increase gross domestic product (GDP) growth in Colombia, given high levels of education and skill amongst arriving individuals, as well as the increasing size of the labor force.3

Purpose of the Toolkit

The purpose of this toolkit is to provide users with guidance on how to strengthen democratic governance in order to manage forced displacement. Its main intended users are practitioners designing programs to help local communities deal with the challenges that forced migration poses. It will also be useful for policymakers grappling with this problem set who need additional information on its sources and options for resolving it.

Local governance is on the frontlines of responding to the challenges that forced displacement presents. This toolkit offers guidance for users to understand and develop context-aware responses that address two mutually reinforcing issues affecting local communities: community tension over scarce resources and lack of awareness of services and civic outlets among host and displaced communities; and lack of planning and coordination among local governments, which hampers service delivery and constrains access to resources. The toolkit seeks to build the capacity of local government to understand and address displacement, and to engage communities on understanding human rights, the root causes of conflict and dialogue facilitation as a tool to defuse conflict over scarce resources.

Overall, the toolkit aims to build trust and cohesion between the government and host and displaced communities, and to strengthen government responsiveness and accountability among all segments of society. This resource also outlines governance solutions to displacement by providing case studies and lessons learned on how to strengthen civic engagement, resolve conflicts and raise awareness of human rights in a context affected by forced displacement.

Methodology

This toolkit was developed by the International Republican Institute (IRI) in collaboration with local facilitators in Colombia and Uganda. IRI piloted the toolkit in Colombia, Uganda and Lebanon. IRI incorporated lessons learned from the pilot activities into the development of this toolkit.

Each module walks through the guiding questions that outline concepts central to social cohesion and displacement. The modules also list key definitions, noted in blue, that are important to understand when working in a context affected by displacement. The reflection questions throughout the modules are critical to use as they help the reader to apply the major concepts to real-life situations and problems. Lastly, key takeaways at the end of each module outline the major lessons learned and provide a recap of the overarching themes.

Module Overview

- Conceptual Grounding in Social Cohesion and Displacement – This module lays the foundation for understanding the importance of social cohesion, the effects of social cohesion in a society and factors that shape social identity. This module clarifies the different terms and concepts regarding social cohesion, human rights, refugees, migrants and internally displaced people (IDPs). In addition, the module offers insights into the different rights and laws that protect refugees in different parts of the world.

- Civic Engagement and Collective Action – This module outlines the concepts of governance, civic engagement and the role of the local government in addressing displacement. It also covers a key tool to address community challenges and displacement: strategic planning. The module also outlines how to undertake the strategic-planning process, map risks and disruptions, and revise the strategic plan based on the fluid nature of displacement.

- Conflict Resolution and Integration – The final module focuses on conflict resolution and community dialogue facilitation. It begins by defining what conflict is, outlines the various phases of conflict, covers the best practices for dealing with conflict throughout the various phases, and finally walks through methodology on how to facilitate dialogue. The goal is to create a holistic understanding of conflict so that political leaders and citizens alike can facilitate dialogue to both prevent and mitigate conflict in displaced and host communities.

Module 1: Conceptual Grounding in Social Cohesion and Displacement

This module lays the foundation for understanding the importance and effects of social cohesion, as well as the factors that shape social identity. This module clarifies the different terms and concepts regarding social cohesion, human rights, refugees, migrants and IDPs. In addition, the module offers insights into the different rights and laws that protect refugees in different parts of the world.

Key Terms

- A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”

- Internally displaced people, according to the United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, are “persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized state border.”4

- A migrant is someone who changes their country of residence, regardless of the underlying reason for migrating or their legal status while migrating. The term “migrant” refers to a variety of legal statuses, including migrant workers, smuggled migrants and international students.5

GUIDING QUESTIONS:

1.1 What is the state of global forced displacement?

1.2 What is social cohesion?

1.1 What’s the state of displacement globally?

By the end of 2019, 79.5 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence or human-rights violations. That was an increase of 2 million people over the previous year, and the world’s forcibly displaced population remained at a record high. This includes: 26 million refugees, 45.7 million internally displaced people and 4.2 million asylum seekers.6 During the same period, 272 million people had migrated internationally.7

The terms “refugee,” “migrant” and “internally displaced person” are often used interchangeably but carry distinct levels of protection and obligation. All refugees, asylum seekers, IDPs and migrants are due universal human rights, including the right to life and liberty, freedom from slavery and torture, freedom of opinion and expression, the right to work and education, and many others.8

The 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 protocol guarantee certain protections for asylum seekers and refugees. The international legal principle, non-refoulement, prohibits governments from returning asylum seekers or refugees to countries where they may be at risk of persecution, murder or other forms of human-rights violations.9 Asylum seekers and refugees are due the same rights and basic assistance as any other foreigner who is a legal resident. For example, refugees must be granted identity and travel documents to allow them to travel abroad. However, the legal architecture allows states to opt out of guaranteeing certain protection and to develop laws and strategies based on political will.10

IDPs do not have a special legal status because they are entitled to all human rights guaranteed by their country to citizens. However, they encounter significant barriers in accessing them because, by nature, the government is often a driving force behind their displacement. Similarly, there have also been massive gaps in the protection of migrants. Migrants are particularly vulnerable to human-rights abuses, violence and hostility.11

A Note on Terminology: Throughout this toolkit, IRI will utilize the term, “displaced people” or “displaced communities,” in reference to refugees, asylum-seekers, IDPs and other individuals displaced against their will. While some lessons can be applied to voluntary or mixed migration, the primary objective is to help local actors manage displacement.

Spotlight on Colombia: The Special Stay Permit12

Nearly 2 million Venezuelans have fled to Colombia since 2015, leaving the country’s national and local governments scrambling to manage the rapid surge of Venezuelan migrants, in addition to Colombians returning from Venezuela. Colombia has facilitated access to rights and services through various legal tools, chief among them the Special Stay Permit (PEP in its Spanish acronym).13 The PEP is granted to any Venezuelan who entered the country with a passport before November 29, 2019. It is also available to individuals in an irregular situation but holding an offer of employment for a period of at least two months up to a maximum of two years.14 Migrants who have a PEP have regular status and can stay in Colombia for two years. As such, they have access to healthcare, education and employment services.

In August 2019, the Colombian government created a new path to citizenship for Venezuelan children born in Colombia since August 2015. This means that children who were previously born stateless can now obtain Colombian citizenship, and thus access to education and healthcare.15

Migrants without a PEP are considered irregular migrants, but there are laws that guarantee their rights. The constitution of Colombia also ensures that anyone in an emergency, regardless of migration status or race, will receive emergency services and aid. Irregular migrants have access to fundamental rights, including access to public education regardless of immigration status as well as emergency healthcare services, vaccinations and childbirth services.

1.2 What is social cohesion?

Social cohesion is an important driver for prosperity, peace and democracy by ensuring that societal development is equitable.16 Social cohesion can be defined as the “glue” or “bonds” that keep society integrated.17 It signifies that community members are included in governance systems in meaningful ways, and involves creating shared values, decreasing inequalities and creating a sense of common narrative.18

In a cohesive society, all groups — regardless of race, ethnicity or class — possess a sense of belonging and are able to participate in society.19 A key part of building a cohesive society is understanding and respecting social identities. Factors that can determine identity are depicted in Image 1 below, and include race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, religion, language, occupation and class. Social identity can be shaped by history, experiences, decisions and interactions.20

Persistent inequality and adversity resulting from discrimination, social stigma, intolerance and stereotypes can exclude segments of a population and push them to the margins of society. As each individual has different social identities, they may identify with multiple dominant or multiple marginalized groups at the same time. Understanding social identity is critical to interrogating biases or stereotypes of different groups, including displaced populations.

Intersectionality refers to the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as gender, age, race, religion and class as they apply to a given individual or group, which create overlapping and interdependent systems of privilege or marginalization. By using an intersectional lens to examine identity, one can look at the various levels of marginalization that are related to different, overlapping identities. Sometimes, a person can receive privilege from one identity but become at risk because of another.21

Module 2: Civic Engagement and Collective Action

This module outlines the concepts of governance, civic engagement and the role of the local government in addressing displacement. It also covers a key tool to address community challenges and displacement: strategic planning. The module outlines how to undertake the strategic-planning process, map risks and disruptions, and revise the strategic plan based on the fluid nature of displacement.

GUIDING QUESTIONS:

2.1 What avenues for civic engagement can help promote social cohesion?

2.2 What is advocacy and why is it important to help address displacement issues?

2.3 How can local government actors develop responsive strategic plans?

2.4 How should strategic plans be modified to different scenarios or risks?

2.1 What avenues for civic engagement can help promote social cohesion?

Community residents can make their voices heard by participating in political and policymaking processes through civic engagement.22 Civic engagement is a way to encourage community participation with issues of public concern, such as service delivery and peaceful coexistence. It can help hold governments accountable for community needs and individual rights, as well as create a sense of community for all individuals, including displaced populations. Some common barriers to civic engagement that displaced populations face include fear of getting involved in public affairs, limited knowledge of the way that the new systems work, lack of time between jobs and home duties and lack of language proficiency.

Case Studies: Civic Engagement Among Displaced Populations

Neighborhood college: In order to demystify community participation, services and the role of the local government, a diverse group of refugees and immigrants in the United States came together in their neighborhood to encourage their communities to become more involved in local government.23 In collaboration with the county government, they created a neighborhood college, which introduced refugees and immigrants to the county government, including how the various boards and commissions can incorporate community input and participation.

Refugee Welfare Committees: In refugee settlements in Uganda, individuals are elected into Refugee Welfare Committees (RWCs). RWC leaders serve as liaisons between the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), service-delivery partners and refugee communities in the settlements. The RWC structure mimics that of the local council in the host community. The RWC system gives a platform for refugees to participate in decision-making processes in Uganda, as well as a pathway for communication with OPM, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) operating in settlements. RWCs are often invited by the local councils (LCs) to participate in district planning meetings by the OPM and local government offices. These district planning meetings typically include discussions around budgeting and disaster-preparedness planning. Thus, through the creation of a civic engagement body, refugees are able to have similar community negotiating power to the LCs in the host community.24

2.2 What is advocacy and why is it important to help address displacement issues?

Advocacy is a key tool that can unlock resources at the heart of mitigating social cohesion challenges. It not only helps achieve policy change, but it also ensures local interests and needs are incorporated into national level strategy and international partnerships, thus increasing the legitimacy, relevance and influence of local actors. Local government and civic actors alike can help advocate for local concerns to create partnerships and programs, as well as access funding from international and national stakeholders.

Broadly defined, advocacy consists of organized efforts to influence laws or policy and encourage participation in the decision-making process. Advocacy increases community awareness, calls attention to specific issues and proposes solutions. By advocating for responsive laws, resource allocation, policies and initiatives, communities can foster social cohesion and inclusion at the local level.

Advocacy can take place with, by or for people affected by laws and policies. Specifically, local governments and civic actors may advocate on behalf of displaced and host communities, in partnership with them, or bolster advocacy efforts that are led by these communities. There are benefits and disadvantages to each approach, but in all circumstances it is important to consult the populations affected by the advocacy issues at hand.

To effectively advocate for resources, it is first important to understand the following: existing laws and regulations; the current status of displacement in the community; existing resources; key decisionmakers and barriers and solutions. Based on this understanding, the following process may be useful to consider when designing advocacy plans and strategies:

- Identify the problem and select an advocacy focus area. If the focus is to advocate for a larger municipal budget to manage the displacement situation, define what the funds will be utilized for.

- Set objectives that define clear and measurable targets to address the problem identified.

- Identify stakeholders, including decision-makers, partners and spoilers. Design an engagement strategy and mobilize actors such as citizens, displaced people, civil society, political parties, and influential actors such as religious or community leaders.

- Articulate policy positions and undertake advocacy activities. Advocacy activities can involve the following: press releases, coalition building, information distribution and media campaigns, roundtables or events, and protests, among other tactics.

Potential focus areas of campaigns on displacement issues can include advocating for the below:

- Greater central government resource allocation or funding from international partners to address local community needs.

- Meaningful participation of displaced populations in informing and monitoring community plans and budgets, like those created by municipalities or districts.

- Increased responsiveness of national displacement or migration policy to the local level.

- Resources for emergency response or to address changes in displacement patterns.

- Greater protection for the human rights of displaced people, and expanding national-level access to services by displaced and host communities.

- Increased awareness of local needs and data on the displacement context.

To ensure advocacy is effective and targeted to the issues at hand it is important to undertake the following across all phases of such strategies. First, it is important to constantly stay up to date of policy and legal developments related to the advocacy topic. This will shed light on various levers and entry points that can be built on through collective action. Second, consult and find ways to incorporate local concerns, including of both displaced and host communities. This will help guarantee that advocacy issues are responsive and targeted. Third, continue to assess the context of displacement and social cohesion in the community. Displacement patterns may change over time, and it is important to consider how tension may arise between various segments of the community. This should then be incorporated into ongoing advocacy campaigns to ensure messages are data-driven.

2.3 How can local governance actors develop responsive strategic plans?

Strategic planning is a process used to identify a group’s long-term goals and to determine the specific actions the group should take to achieve these goals. It aims to outline issues, analyze internal and external factors, and define the roles and duties among the team and other stakeholders. It also involves outlining which interventions will help achieve identified objectives and evaluate the success of various initiatives.

In some contexts, local governments help manage displacement by providing public services and working to meet the basic needs of health, education, water, housing, environmental sanitation and recreation. They can also disseminate information faster in their specific locations and serve as an intermediary between other government institutions and their community.

Strategic planning can be an effective tool to manage displacement. It can help define community priorities, deepen multi-sectoral engagement and establish concrete objectives to address issues emanating from displacement. Municipalities can create plans that open access to services, promote local economic development and encourage community cohesion activities. For example, in Uganda, the district council is required to prepare an integrated development plan, which offers a useful opportunity to consult village and parish priorities. Bear in mind that each municipality experiences the displacement phenomenon differently, from its particular social and historical context.

Case Study: Municipal Development Plan for the City of Ipiales, Colombia

Ipiales developed a municipal development plan, which includes guidance on how to manage

the migration influx, seeing as Ipiales is a border municipality that already hosts 4,767

Venezuelan migrants. The plan focuses on providing humanitarian aid, healthcare and other

government services to migrants in accordance with international law as stated in its strategy

section: “We will assist refugees and victims of the migratory crisis that affect the municipality

in accordance with international law applicable for this topic.”25 The plan also mentions 13

programs catered to migrants that provide the rights to security, cultural activities, protection,

healthcare, recreation, community participation and financial opportunities.

Here are a few steps that will help you develop a strategic plan:26

- Step 1: Initiate the strategic-planning process with group members or with people who want to work on a cause or initiative together.

- Step 2: As a group, gather information to assess the group’s current strengths (internal), weaknesses (internal), opportunities (external) and threats (external).27

- Step 3: After you conduct the assessment, begin the process of brainstorming ideas for action that should be taken by the group.

- Step 4: As a group, decide on the best ideas for action to be taken.

- Step 5: Write the action steps down in a document.

- Step 6: Evaluate the strategic plan to determine whether it meets your overall objective.

Recommendations on how a strategic plan can address displacement issues:

- Promote conflict- and xenophobia-prevention activities, and design indicators to measure the baseline and impact of displacement in cities. Develop programs on peaceful coexistence, particularly among schools, which facilitate community cohesion and prevent discrimination.

- Set up a hotline that will allow the community to voice its concerns. It is important to strengthen community support for the strategies implemented by the local government and the national government.

- Promote trainings and workshops for educational institutions on the rights of displaced children and how to help them adapt to their new schools. Make sure you conduct periodic consultation with educational institutions on the number of vulnerable people, according to age, sex, condition of vulnerability and country of origin.

2.4 How should strategic plans be modified to different scenarios or risks?

Normally, individuals, organizations or communities create static strategic plans. With scenario planning, think about the current plan, imagine disruptions and then re-plan based on how the disruptions would impact the ability to reach your goals. It is the systematic process of outlining alternative futures and preparing responses to shifting political, economic and social currents.28

To adapt strategic plans, reflect on the risks or unexpected occurrences that can impact the plan and how to prepare for them. A risk is “the potential for an adverse event or result to occur.” There are several types of risks:29

- Risks associated with the context, such as political changes, an outbreak of violent conflict, both sudden and slow-onset disasters and pandemics.

- Risks associated with programming, which means that interventions are not implemented well or have the potential to exacerbate social tensions.

- Institutional risk, which includes management failures, reputational risk and exposure of staff to security risks.

Displacement is fluid in nature, with individuals moving to, from and through communities. In order to mitigate potential disruptions and unintended consequences on target communities, maintaining an understanding of interactions between dynamics and actors can help ensure the intervention is responsive to how things may change over time.

Do no harm is a helpful principle for understanding how policies and programs may interact with social-cohesion issues. Do no harm means understanding how projects interact with community dynamics, and then acting upon this understanding to minimize the negative impacts and maximize positive impacts. It is important to mitigate risks by planning for possible risk scenarios and developing a response plan.

Tips to Plan for Risks

- Assemble a crisis committee and conduct a scenario analysis. A crisis committee is a group of experts and can include individuals with a range of expertise and backgrounds, including academics, civil society and political actors. Together, facilitate an exercise to envision how different scenarios may play out and which risks are most feasible. Then sketch out different alternatives for the scenario, including the possible outcomes of certain decisions or programs.

- Consider the impacts of a risk or crisis on different segments of the population. Crises affect every individual in different ways, particularly those who may already be disadvantaged. In any unforeseen event, consider the uneven impacts and plan accordingly.

- Monitor global trends. Establish a special unit that is responsible for assessing changes in context and projecting future scenarios.

- Utilize the strategic planning process to assess risks. The strategic-planning process is an important moment for reflection on key priorities and programs. It can also be leveraged to analyze the most pressing events and trends that may impact the goals over time.

Module 3: Conflict Resolution and Integration

This last module focuses on conflict, conflict resolution and community dialogue facilitation. The module begins by defining what conflict is, outlines the various phases of conflict and best practices for dealing with conflict throughout the various phases, and lastly walks through methodology on how to facilitate dialogue. The goal is to create a holistic understanding of conflict so that anyone, including political leaders and citizens alike, can facilitate dialogue for community conflict resolution to both prevent and stabilize conflict in displaced and host communities.

GUIDING QUESTIONS:

3.1 What is conflict?

3.2 What are the different phases of conflict?

3.3 How do you facilitate dialogue?

3.1 What is conflict?

When a country receives an inflow of displaced people it can lead to a sudden and drastic increase in the population, which strains the host country’s capacity to deliver services. These exogenous shocks can result in conflict.30

A conflict is a struggle or a difficult/problematic situation between two or more parties that can sometimes result in confrontation or physical violence. Some examples of situations where conflict can arise include resource scarcity and differences in beliefs, customs, culture, interests, thoughts and values. Displaced and host communities can encounter the following common challenges:

- Displaced people often have difficulty with social and economic integration, mainly due to lack of civil compromise in the community and the conditions in which they live.

- The host community has unresolved issues and insufficient infrastructure and resources. This has worsened due to COVID-19.

- Both communities have difficulty accessing healthcare services, educational opportunities and humanitarian assistance. In some cases, the host community already lacks resources and the displaced community receive assistance from international aid, leading to some tension between the two populations.

- Misinformation and hate speech on social media can amplify tensions and xenophobia.

It is important to note that conflict can be both constructive and destructive. Constructive conflict resolution can help to avoid stagnation, stimulate interest and curiosity in other perspectives, encourage personal and social change, and help to establish both individual and group identities. Once the benefits of positive conflict resolution have been experienced by a community, they increase the likelihood that positive solutions will be reached in future conflicts.

At the same time, conflict can also have destructive effects. It can lead to vicious circles that perpetuate antagonistic, hostile relationships with others, and create the perception that conflict and violence are the only ways to resolve disputes. The ultimate challenge for communities when building social cohesion and peace is to engage in conflict without escalating it toward destructive methods of confrontation.31

3.2 What are the different phases of conflict?

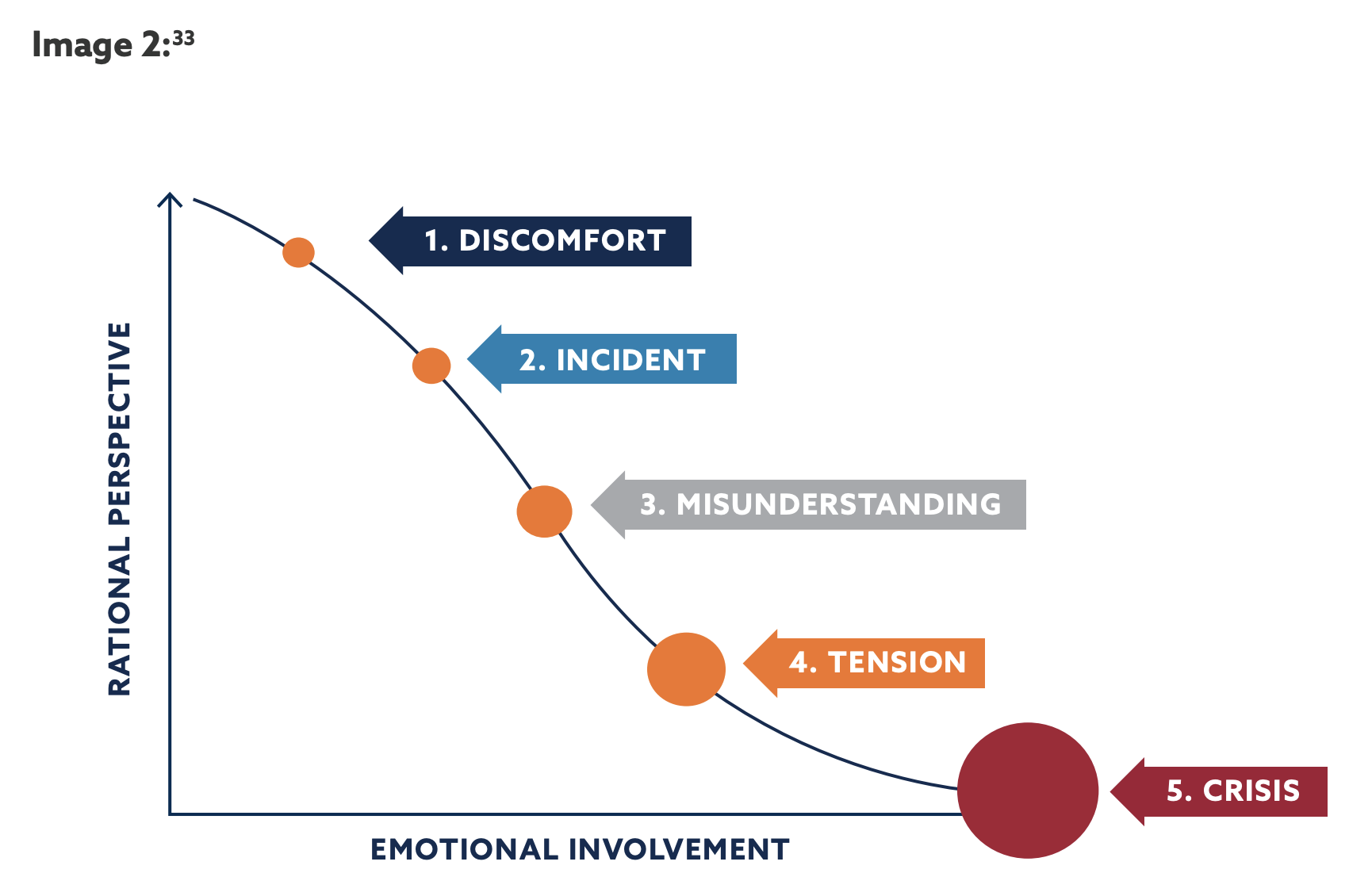

There are several phases of conflict. If you can identify them, it will make intervention and resolution strategies easier:32

- Discomfort: There is a misunderstanding between two or more parties, and it is detected that something is not right. At this point, you think it could pass and might minimize the importance of this phase.

- Misunderstandings: Assumptions are made regarding what the other party wants, needs or is concerned with. Stereotypes can cloud judgment of the validity of what the other party wants.

- Incidents: The situation escalates in response to specific incidents. Often hurtful things are said or done and misunderstandings become more complex.

- Tensions: Tension escalates with underlying misunderstandings and reoccurring incidents. Already the relationship with the other is one of antagonist-enemy, and allies are sought to build support for yourself/your group. This can lead to polarizing the situation and social cohesion in the community can begin to decrease.

- Crisis: This is the critical point; it is the moment when the conflict becomes evident through active conflict engagement. There is often an urge to fight, confront or flee.

What Can You Do Throughout These Phases?

In each phase, it is important that participants and facilitators engage in active listening to prevent the situation from escalating. The role of a mediator throughout these phases is to intervene and facilitate the solution to the problem, and to utilize conflict-resolution tactics at the earliest phase possible.

Things to Keep in Mind:

- Good relationships and good communication do not necessarily mean that conflict, underlying misunderstandings and tensions do not exist.

- In cross-cultural communication, the same expressions can generate different meanings.

- Peaceful coexistence is not only the responsibility of others; we build it together and it starts with each of us.

3.3 How do you facilitate dialogue?

Dialogue is a critical tool used to deescalate tension, foster shared understanding and increase understanding about different world views. Through dialogue, participants can speak to their own experiences, understand other beliefs and value systems, and work together for a shared understanding of the situation.34

A dialogue facilitator should provide a safe environment for participants to be able to discuss sensitive issues from the community’s perspective as well as from members’ personal lives. In order to provide this, it is critical that facilitators reflect on why the dialogue is important and their own preconceptions and misconceptions.35

The facilitator should ensure that the environment is an open and nonjudgmental space, and should encourage everyone to listen to others and understand differences. It is also critical that all participants have the opportunity to speak while also being encouraged to challenge their own worldviews.36 Dialogue about conflict is often deeply personal, which can lead to strong emotions and opinions. It is critical that participants feel they can express these emotions without negative consequences.37

Phases of Dialogue Facilitation38

The dialogue facilitator should lead conflicting parties through several main phases:

- Getting to know each other and elaborating the issues: All parties should have the opportunity to present their thoughts and opinions on what the issues are.

- Tip: Visualize issues and perspectives, but do not write them down verbatim. This allows the party that raises a concern to feel heard, but also does not constrict that party’s perspective to specific language.

- Sharing perspectives and creating a deeper understanding: Once all parties have presented their thoughts, participants should elaborate on their perspectives. This phase is the most difficult but also the most critical for laying the foundation for solutions. Allow conversation to happen but actively moderate so that all parties’ perspectives are respected. An indicator of success in this phase is when one party expresses surprise about someone’s perspective or softens their perspective on a specific topic.

- Tip: Use methods that make people’s concerns and feelings heard; this can include reframing questions and sidebar dialogues.

- Generating inclusive options: Allow for options that are inclusive to everyone’s thoughts and opinions to develop during conversation. Do not evaluate the options yet; rather, create an environment for open and safe brainstorming. Encourage a wide variety of perspectives and solutions.

- Discussion and evaluating the options: Put together a list of criteria on how to choose from the options that were brainstormed. Ensure that there is a reasonable consensus on how to move forward.

Managing Deadlocks and Difficult Conversations During Dialogue Sessions39

Sometimes emotions during dialogue sessions can run high, leading to difficulties such as deadlocks and tense situations. Some methods to overcome barriers include:

- When emotions run high and participants express anger or aggression, respond using a “first aid empathy” technique, wherein you ask the participants to verbalize their feelings and explain why they feel that way. Then walk through some steps on how to resolve these feelings.

- Set rules for dialogue, specifically for communication styles that are permitted or not permitted (e.g., shouting and interrupting). When participants start to break these rules, gently remind them to be respectful.

- Work with the participants during breaks when there is difficulty with one or two specific people, to try and resolve their feelings on the side before returning.

- Collect information prior to the dialogue about the issues that will be brought up so that you can refer to the facts if there are disagreements about events or contexts. If there are specific points that need to be addressed, bring in expertise from people who know how to solve these specific issues.

- Create a team within the dialogue that is responsible for intervening when there is a deadlock.

Footnotes

- “1 Per Cent of Humanity Displaced: UNHCR Global Trends Report.” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2020, unhcr. org/en-us/news/press/2020/6/5ee9db2e4/1-cent-humanity-displaced-unhcr-global-trends-report.html.

- “Forcibly Displaced.” World Bank Group, 2017, openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/25016/Forcibly%20 Displaced_Overview_Web.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y.

- Bahar, Dany and Megan Dooley. “Refugees As Assets Not Burdens: The Role Of Policy.” Brookings, 6 Feb. 2020, brookings.edu/ research/refugees-as-assets-not-burdens-the-role-of-policy/.

- “Compact for Migration: Definitions.” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, emergency.unhcr.org/entry/44826/idp-definition.

- “Who is a Migrant?” International Organization for Migration, 2019, iom.int/who-is-a-migrant.

- “Teaching Human Rights: Practical Activities for Primary and Secondary Schools.” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2004, p. 10, ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/ABCen.pdf.

- “World Migration Report.” International Office of Migration, 2020, publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf.

- “Human Rights.” United Nations, un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/human-rights/#:~:text=Human%20rights%20include%20the%20right,to%20 these%20rights%2C%20without%20discrimination.

- “The Principle of Non-Refoulement Under International Human Rights Law.” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, ohchr. org/Documents/Issues/Migration/GlobalCompactMigration/ThePrincipleNon-RefoulementUnderInternationalHumanRightsLaw.pdf.

- Yayboke, Erol K. and Aaron N. Milner. “Confronting the Global Forced Migration Crisis.” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), May 2018, csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/180529_Ridge_ForcedMigrationCrisi.pdf.

- “Migration and Human Rights.” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Migration/Pages/ MigrationAndHumanRightsIndex.aspx.

- “Services for Venezuelan Migrants in Colombia.” YouTube: International Republican Institute, 6 Aug. 2020, youtube.com/watch?v=6- gClfEEZtU&feature=emb_title.

- “Services for Venezuelan Migrants in Colombia.” International Republican Institute, 2020, iri.org/resource/new-video-services-venezuelan-migrantscolombia.

- “UNHCR Welcomes Colombia’s Decision to Regulate Stay of Venezuelans in the Country.” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 4 Feb. 2020, unhcr.org/news/briefing/2020/2/5e3930db4/unhcr-welcomes-colombias-decision-regularize-stay-venezuelans-country.html.

- Arenas, Gustavo Andres Castillo and Patrick Ammerman. “A Country That Welcomes Migration.” Yes! 19 Feb. 2020, yesmagazine.org/issue/world-wewant/2020/02/19/colombia-venezuela-migration/.

- “Social Cohesion for Stronger Communities.” Search for Common Ground Myanmar, sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/SC2-Facilitator-Guide_ English.pdf.

- Larsen, Christian Albrekt. “Social Cohesion: Definition, Measurement, and Developments.” Centre for Comparative Welfare Studies, Aalborg University, 2014, un.org/esa/socdev/egms/docs/2014/LarsenDevelopmentinsocialcohesion.pdf.

- Fonesca, Xavier, Stephan Lukosch and Frances Brazier. “Social Cohesion Revisited: A New Definition and How to Characterize It.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research vol. 32, no. 2, 2019, tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13511610.2018.1497480.

- “Social Cohesion for Stronger Communities.”

- “New Identity Intersections Resources.” Student Life Spectrum Center, University of Michigan, https://spectrumcenter.umich.edu/article/newidentity-intersections-resources-our-website.

- Pioske, Hannah. “What Does ‘Intersectionality’ Mean for International Development?” CIPE, 8 July 2016, cipe.org/blog/2016/07/08/what-doesintersectionality-mean-for-international-development/.

- “Civic Engagement and Governance” in “How’s Life?: Measuring Well-Being.” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2011, read. oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/how-s-life/civic-engagement-and-governance_9789264121164-11-en#page1.

- “Increasing Refugee Civic Participation: A Guide for Getting Started.” Moisaica, p. 3, cliniclegal.org/file-download/download/public/1400.

- Zakaryan, Tigranna. “Baseline Assessment: Refugees and Local Governance Project — Uganda.” Internal Document prepared for the International Republican Institute, 10 Feb. 2020.

- Diaz, Jarlin. “Plan de Accion Subprograma Gobernanza Migratoria.” Internal Document prepared for the International Republican Institute, 10 Oct. 2020.

- “Strategic Planning: For Your Network’s Future.” IRI Women’s Democracy Network, Internal Training Document.

- A SWOT analysis is part of the strategic-planning process because it helps build on best practices and a concrete understanding of strengths and weaknesses. The SWOT analysis process involves four areas: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

- “Scenario Planning Training.” International Republican Institute, 2020. Internal Training Document.

- “Development Assistance and Approaches to Risk in Fragile and Conflict Affected States.” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 30 Oct. 2014, oecd.org/dac/conflict-fragility-resilience/docs/2014-10-30%20Approaches%20to%20Risk%20FINAL.pdf.

- “Supporting Refugee Inclusion for Common Welfare in Host Countries.” Center for Mediterranean Integration, 2015, cmimarseille.org/programs/ supporting-refugee-inclusion-common-welfare-host-countries.

- “Handbook on Human Security.” Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict, 1 Mar. 2016, gppac.net/publications/handbook-human-securitycivil-military-police-curriculum.

- “Understanding Conflict.” Conflict Resolution Network, conflictstudies.org/books/crskills/chapter/understanding-conflict/#_Toc207699272.

- “The 5 Stages of Conflict.” Symonds Research, symondsresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/02-5-stages-of-conflict-min.png

- Ropers, Norbert. “Basics of Dialogue Facilitation.” Berghof Foundation, berghof-foundation.org/fileadmin/redaktion/Publications/Other_Resources/ Ropers_BasicsofDialogueFacilitation.pdf.

- “Training of Trainers Manual: Transforming Conflict and Building Peace.” Saferworld, 2014, saferworld.org.uk/resources/publications/797-training-oftrainers-manual-transforming-conflict-and-building-peace.

- Cehajic-Clancy, Sabina. “Regeneration: Reconciliation Talks.” USAID, Internal Training Curriculum.

- Ropers. “Basics of Dialogue Facilitation.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.