Georgia Focus Group Research: Qualitative Analysis of Public Opinion Trends Following the 2020 Parliamentary Elections

Executive Summary

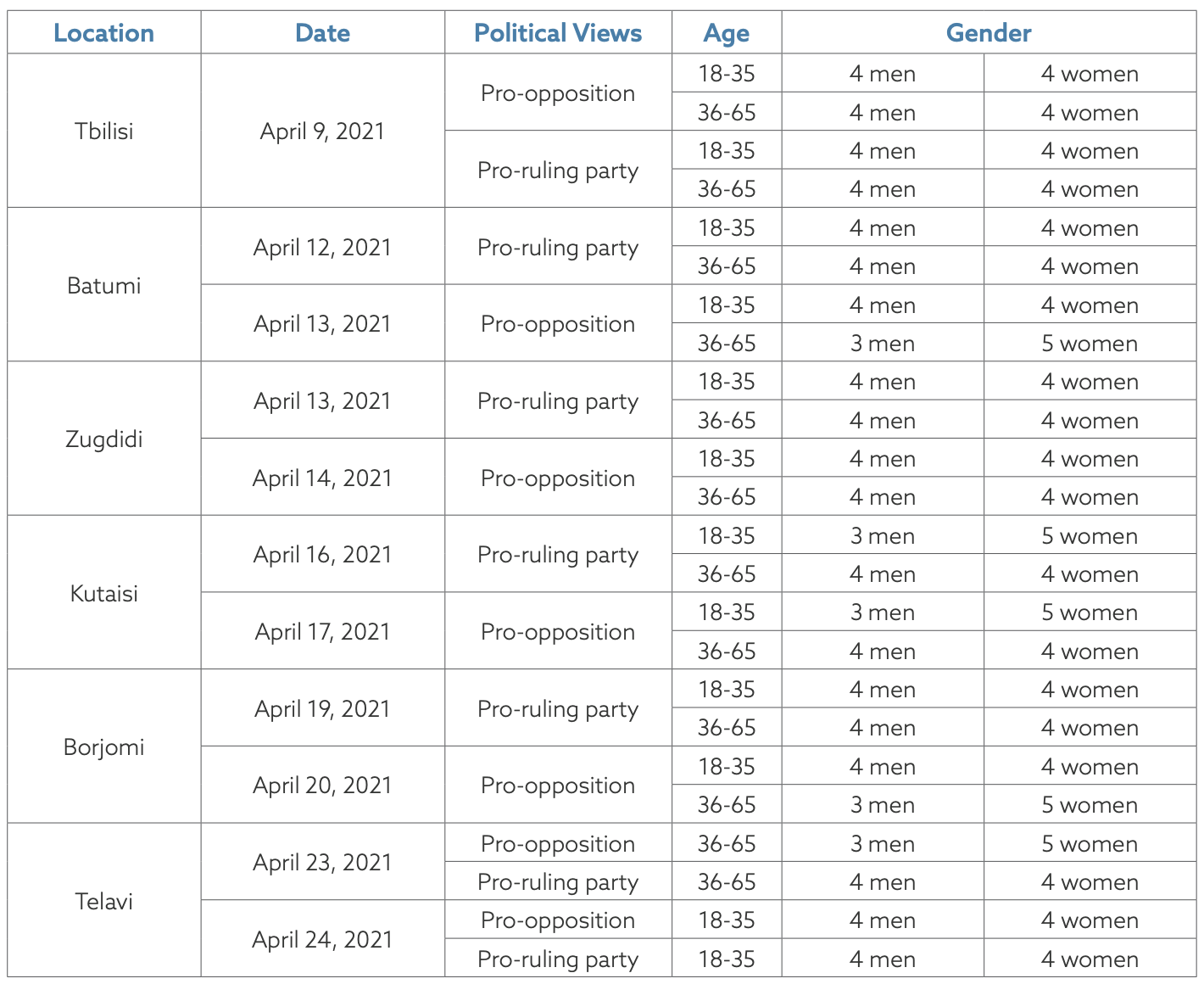

In April 2021, IPM Market Intelligence Caucasus, on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s (IRI) Center for Insights in Survey Research, conducted a qualitative study of public attitudes toward the 2020 parliamentary elections and recent political events in Georgia. Twenty-four focus group discussions were conducted in Tbilisi and five regional cities. The focus groups were held during a period of high political polarization following the 2020 elections. They occurred concurrently with negotiations between the ruling Georgian Dream party and opposition parties that were boycotting parliamentary proceedings over allegations of electoral fraud.

The study analyzed participants’ views of the general political situation and focused on the following topics: the conduct of the 2020 parliamentary elections; political and electoral processes, including avenues for electoral reform; and the post-election political crisis. A primary objective of the focus group discussions was to understand the participants’ perspectives on ways to improve the conduct of future elections in Georgia. The analysis of the information gained from the focus group discussions can inform the development of an electoral reform policy that addresses the needs and priorities of Georgian citizens.

Key Findings

- Participants do not see a way out of the political crisis and are frustrated by the inability of the ruling party and opposition to engage in constructive dialogue and come to an agreement.

- Participants’ mistrust and disappointment with election campaigns over the years has led them to view parties’ pre-election activities as ineffective and insignificant. Parallels between the 2020 pre-election campaigns and previous campaigns contribute to this view.

- When reflecting on the 2020 elections, opposition supporters list numerous serious violations from Election Day. Ruling party supporters categorically deny intimidation and pressure on voters occurred, characterizing such cases as “influence.”

- Participants are unable to define the Central Election Commission’s exact functions and responsibilities or its role during the 2020 elections. However, they believe the CEC’s independence and neutrality are critical.

- Most participants are unaware of, or have only a limited understanding of, the reforms put in place prior to the 2020 elections. According to participants, this is a communication issue, and such information should be delivered to voters more effectively.

Overview

Through this qualitative research study, IRI analyzed public opinions on national politics in the post-election period to gain an in-depth understanding of public perceptions of the pre-election campaign, Election Day, the role of the Central Election Comission (CEC), and the negotiations between the government and the opposition. The discussion was targeted to solicit opinions on the 2020 elections and electoral processes, pinpointing perceived electoral violations and practices that undermine public confidence in the election results. The focus group discussion guide can be found in Appendix B. As common in qualitative research studies, findings from this study do not necessarily reflect the opinions of all Georgian citizens but point to broader trends.

In order to study public attitudes toward the abovementioned topics, 24 in-person focus groups were conducted in April 2021 in six cities of Georgia: Tbilisi, Batumi, Zugdidi, Kutaisi, Borjomi, and Telavi. Four focus groups were held in each city. In addition to the capital, study participants were selected from seven regions of the country. In each of the regions, the focus groups were composed of residents of the cities where the discussion was held as well as different cities and villages of the region. In the Batumi and Borjomi focus groups, participants included residents of two regions: residents of Adjara and Guria took part in the Batumi groups, and participants in the Borjomi discussions included residents of Shida Kartli and SamtskheJavakheti.

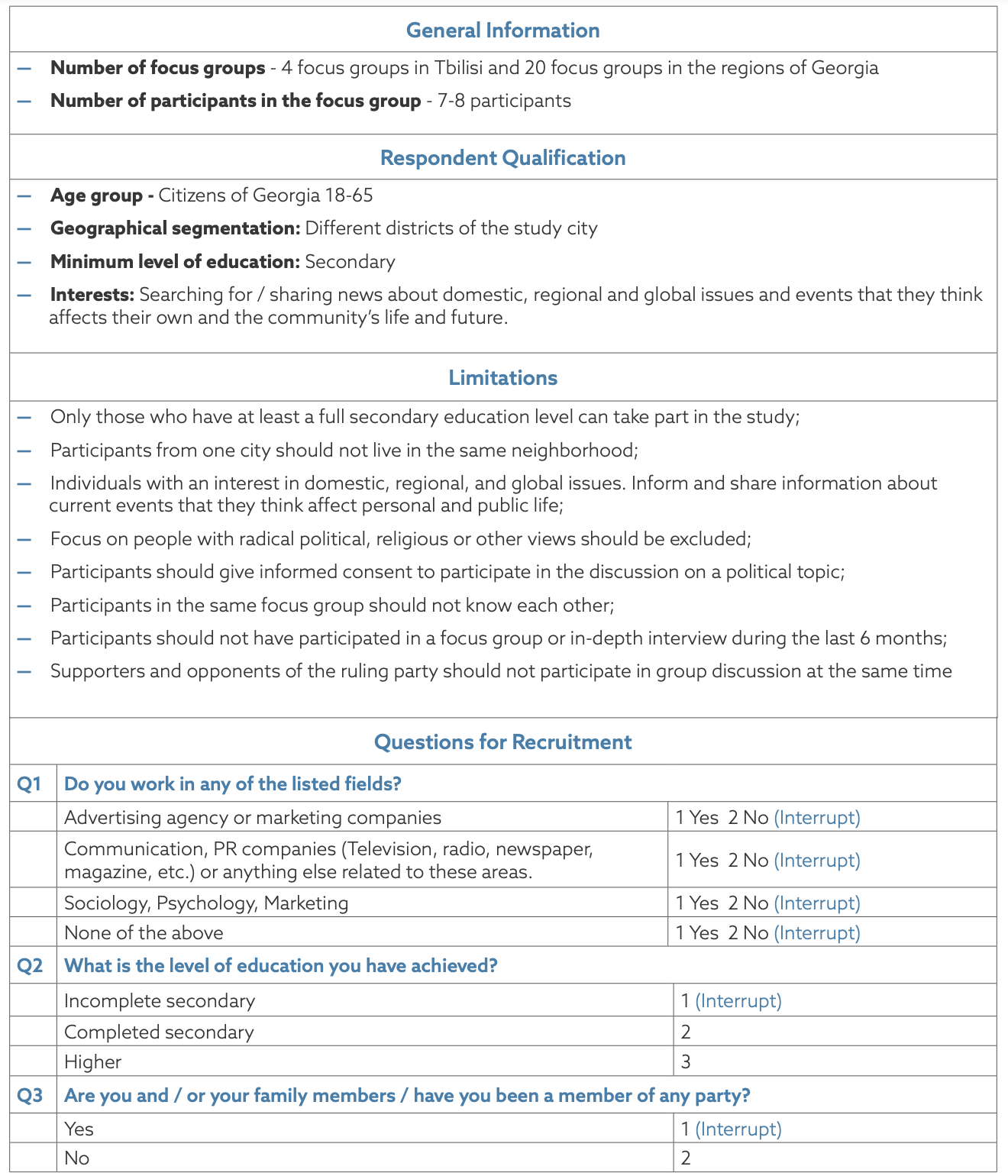

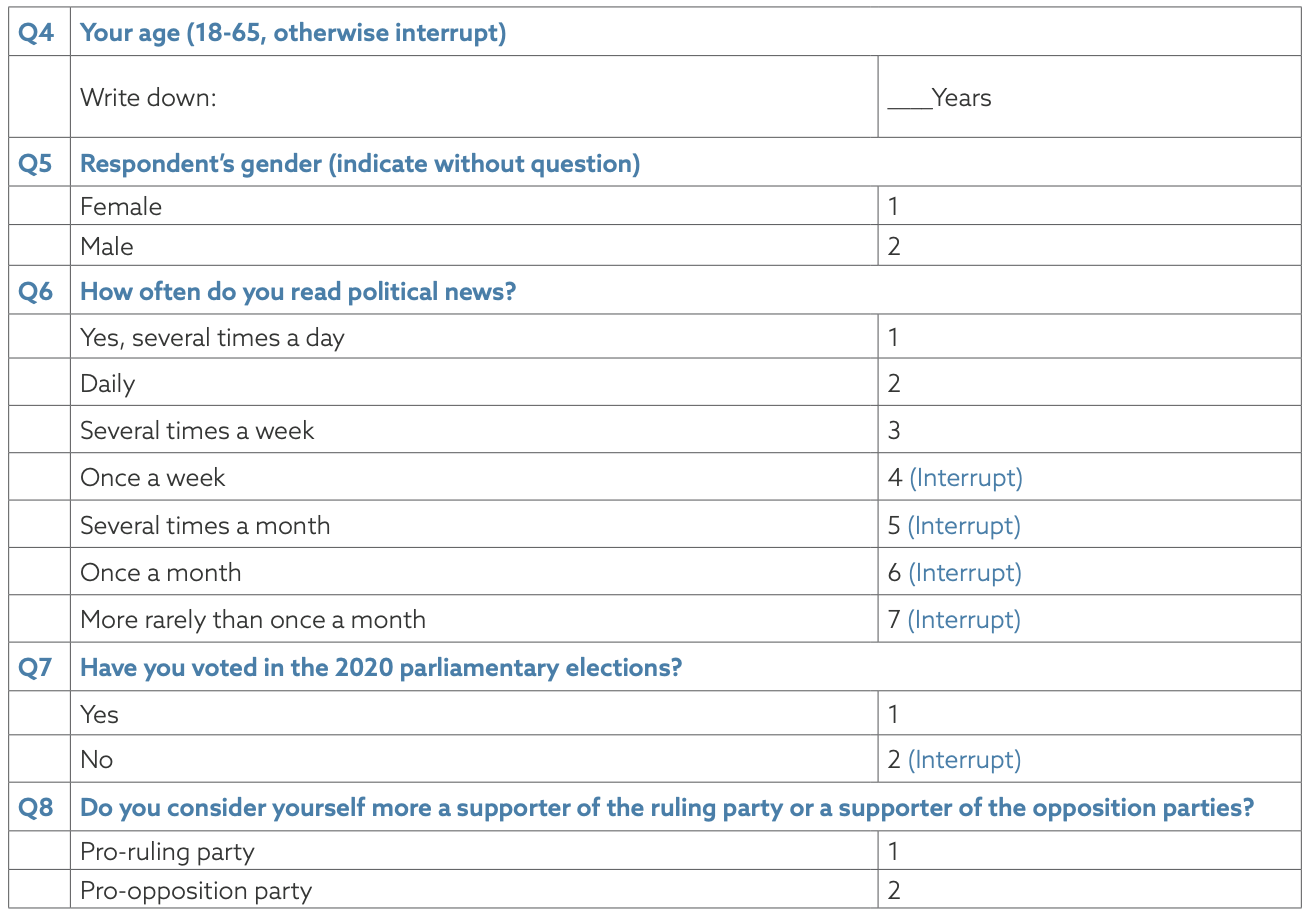

The 192 focus group participants were separated according to age group (18-35, 36-65) and political views (pro-ruling party, pro-opposition). Gender balance was maintained among focus group participants. For most groups, four of the eight participants were male and four were female. Additional information on the methodology with a detailed breakdown of the participant profiles can be found in Appendix A.

Participants were recruited through a pre-compiled screening questionnaire, which can be referenced in Appendix C. Participants were screened for the following characteristics: an active interest in politics (as gauged by how frequently participants read political news), casting a vote in the 2020 parliamentary elections, educational attainment, location, age, and gender. The research participants actively followed the current events in the country through various information sources and were able to express their opinions by using specific arguments.

Context

The October 2020 parliamentary elections were perceived as a high-stakes contest by both the ruling party and the opposition. Following the announcement of the election results, opposition parties launched protests based on allegations of election fraud, citing revised protocols and cases of intimidation at polling stations. Many complaints submitted by local election observation groups and by parties were dismissed for technical reasons, and ultimately recounts did not take place in many of the disputed precincts, contributing to diminished public confidence in the election results. Opposition representatives initially formed a united front, declaring a boycott of parliamentary proceedings and demanding new elections. Tensions rose further following the arrest of opposition leader Nika Melia in February 2021. In negotiations with the ruling party, opposition parties sought the release of Nika Melia and one of the founders of opposition-leaning media outlet Mtavari Arkhi (“Main Channel”), Giorgi Rurua.

Several rounds of negotiations mediated by the U.S. and EU ambassadors were unable to bridge the gap between the ruling party and opposition demands. Following the visit of European Council President Charles Michel, the negotiations were overseen by EU Special Envoy Christian Danielsson. IRI’s qualitative research study took place concurrently with the negotiations mediated by the Danielsson between the government and the boycotting opposition parties. The April 19 agreement put forth by the EU Special Envoy was signed by members of the ruling party as well as some members of the opposition. The signature of the document coincided with the last stage of the focus groups and directly preceded the two discussions held in Borjomi on April 20 and all four discussions in Telavi. The agreement includes provisions related to early elections, the release of Melia and Rurua, justice reform, power-sharing between the ruling party and opposition, and electoral reform. On the subject of electoral reform, the agreement lists several amendments to electoral legislation and practices that are intended to increase public trust in electoral outcomes in the future. Following the conclusion of the research, the Georgian Parliament approved amendments to the Election Code in line with the April 19 agreement on June 28. On July 27, 100 days after the signing of the April 19 agreement, Georgian Dream withdrew from the agreement, maintaining that the agreement had fulfilled its intended purposes and citing the failure of four opposition parties, including the largest opposition party the United National Movement, to sign the agreement.

Findings

Overall, the focus group discussions revealed the participants’ perceptions1 of the 2020 pre-election environment, the CEC’s role in the pre-election period and electoral processes, and electoral reforms. Participants’ attitudes towards political events are shaped by their political sympathies, reflecting the polarized political environment and partisan media coverage. Although the participants frequently describe the situation in similar negative terms, their assessments differ in terms of attribution of responsibility based on their political views. When describing current events, they tend to interpret the facts to align with their political views. Opinions of research participants with similar political views on specific issues are homogeneous and do not vary greatly between regions. While there is not much difference in content, participants often use emotional terms to describe events, and the intensity of participants’ emotional responses varies.

As for differences between age groups, older participants are generally more cautious when speaking. On several topics, especially on the subject of electoral violations, some of these participants refrain from naming specific examples. They express their position and opinion in a mild, measured way as compared to participants in the 18-35 age group. The influence of television news programs and mass media is most evident in the speech of older participants, as information heard on television is frequently used to make an argument.

People should get united against [the government]. People should come out in the streets to change something, no one should be intimidated, they leave no other way.

Telavi, 18-35, male, pro-opposition

In the younger age group, views are expressed in more radical terms. They perceive the opposition and the ruling party as opposing camps. They express their position sharply and boldly on any issue. Because they consider the information received from television to be less reliable, they try to consult different information sources. Therefore, participants in the 18-35 age group have more information on specific issues, and their speech is more grounded in facts, citing specific examples in their arguments.

The following key findings describe the study participants’ attitudes in detail.

Finding 1

Participants do not see a way out of the political crisis and are frustrated by the inability of the ruling party and opposition to engage in constructive dialogue and come to an agreement.

The political situation is described as chaotic, tiring, and tense by the study’s participants, regardless of age, political views, or region. Such an assessment is based on recent events in the country: the opposition’s doubts regarding the validity of the 2020 election results, opposition-led protests, and the lack of agreement between the two sides during negotiations. The negotiations were one of the most emotionally charged discussion topics, although most participants lack complete information about the specific issues being negotiated. Opposition and ruling party supporters among the study participants are considered to be on opposing sides. Moreover, participants do not see a way out of the current political situation. Some participants are irritated by the fact that the situation necessitates the intervention of a third party (referring to the role of international actors as arbiters of the conflict). This is not because the mediator is unacceptable to the study participants, but because this situation highlights the inability of the opposition and ruling party to engage in dialogue.

They must agree to take care of the country and the people, pull them out of the swamp to overcome this pandemic… If you bring this person from abroad, they will not be able to negotiate on their own.

Borjomi, male, 18-35, pro-ruling party

Participants refer to the political situation as chaotic due to the ineffectiveness of the negotiations. Participants express that both parties are not particularly interested in resolving the crisis. Participants recognize the need for compromise, but they are unable to agree on which side should make concessions. It is difficult for the research participants to discuss this question in a constructive manner, to formulate their position logically and using objective terms, and to describe solutions to overcome these difficulties in a consistent manner. Their conversation is framed by the idea that this challenge must be solved in the interests of the people — the voters. They link this to a sense of security and stability, which they refer to as “peace” during the conversation.

If they really think about the country, both sides should make some compromises.

Zugdidi, male, 36-65, pro-opposition

In terms of whom participants hold responsible for creating the present political conditions and for overcoming the crisis, participants’ positions are split according to their party allegiances. The opposition demands for snap elections and the release of Giorgi Rurua and Nika Melia caused mixed reactions among participants regardless of their political leanings.

Most participants, including both pro-government and pro-opposition participants, agree that the way to overcome political challenges is through establishing consensus. These participants see the need for concessions from both sides. In their view, peaceful negotiations are essential, and both sides must be represented in Parliament in order to effectively voice the needs of the population and care for the people. This conclusion aligns with the results of IRI’s February 2021 opinion poll,2 which showed that the majority of voters (60%) do not support the opposition’s boycott of parliamentary proceedings. A sense of security and stability is crucial for these participants, and the political crisis is perceived as dangerous. They believe that peace can only be achieved after both parties sign the document proposed by the EU Special Envoy. Older participants are more likely to express a desire to overcome the political crisis through peaceful negotiations than those in the younger age group.

I still think that some agreement should be reached through negotiations. They have to think about helping people. They do not go to negotiate and the people are trapped in between…the people are in trouble at this time. We no longer have jobs, everything has become more expensive…They have to find some solution. Something needs to be improved in this country so that people can breathe a little, too.

Tbilisi, female, 36-65, pro-opposition

[In the negotiations] both are responsible because an agreement must be reached. People are put in the middle of their argument.

Kutaisi, female, 36-65, pro-ruling party

These participants tend to see the solution as snap elections. Supporters of the government think this will prove the credibility of the 2020 election results and that the opposition will recognize the choice of the majority of the population. The opposition supporters from this group also consider snap elections as a way forward, but only because a real winner will be revealed. If the parties reach an agreement on other points of the negotiations, these participants are ready to concede the demand for the release of Giorgi Rurua and Nika Melia. During the discussion, these study participants were unable to form structured opinions about which side should compromise, what agreements should be made from each side, and which red lines exist where concessions are unacceptable. They believe that reaching a compromise from both sides is a good interim step toward stabilizing the chaotic political situation. Members of this group are likely to sympathize with the side that shows the way out of the current state of uncertainty.

In my opinion, the fact that the opposition has not yet entered the Parliament has awakened the government a bit. The representatives of the European Union also came to their senses and realized that there is no such happy life in Georgia.

Tbilisi, male, 18-35, pro-opposition

In contrast to the multi-partisan group advocating compromise on both sides, two groups have more polarized attitudes and expect the opposing side to make concessions during the negotiations.

If today the opposition thinks that the government is illegitimate and has stolen votes, then negotiating with them is illegitimate itself, it is illegal. I think that if negotiations take place, e.g. This process has gained legitimacy. If I think they have obtained this mandate illegally, I should not have made an illegal deal with them… If I protest, I must protest to the end.

Tbilisi, male, 18-35, pro-opposition

Opposition supporters with more radical views, who comprised approximately a third of pro-opposition participants, believe that by protesting, the opposition has awakened the government and EU representatives as well. Only protests, they believe, can adequately express Georgia’s current difficult position. In their view, the government has violated the democratic principle of multipartism by rigging the 2020 election results. Citing election fraud, the participants say the current government is unconstitutional. The failure to properly count the votes, according to which the number of votes tallied exceeded the number of ballots cast, is used by the participants to support an argument for the CEC’s (and consequently, the government’s) lack of qualifications, participation in electoral fraud, and unprofessionalism. According to these participants, if the opposition were to enter Parliament, the government would use this to strengthen its narrative that democratic elections were held in Georgia. This group of participants supports the opposition boycott, regards Giorgi Rurua and Nika Melia as political prisoners, and believes that civil disobedience should be used to call the government’s legitimacy into question. Among those calling for Rurua and Melia’s release, for the most part, these participants are United National Movement voters, who consider the issue of their release to be more important than members of other opposition parties do. Bidzina Ivanishvili, the founder and former head of the ruling Georgian Dream party, is viewed as a major political figure by them, and the government team is viewed as his puppets. These participants do not see the point of negotiating with the ruling party. In their opinion, constructive negotiation methods will not be effective because pursuing minor reforms would not be the right decision. These participants see the need for systemic change and think that reforming the current government makes no sense; instead, the government must change from the ground up. Civil disobedience, a coup, and a new ruling team, in their opinion, would be the best way out of this situation.

There is nothing to negotiate. The whole world claims that it is not rigged and they say it is rigged. Which compromise should we make? What is the government’s role here?

— Batumi, male, 36-65, pro-ruling party

As already mentioned, during the study, negotiations between the government and the opposition resulted in an agreement, which was signed by the ruling party and some members of the opposition before the focus groups held in Telavi. This development irritated opposition supporters in the Telavi focus groups, the majority of whom viewed the signing of the document as a mistake by the opposition.

Opposition protests have a negative impact on the country. For example, when an investor arrives or something special has to happen in the country, the situation is such that there is a boycott, the opposition does not enter Parliament, they cannot do business with us. Investment is not possible and this has led to a bad economic situation.

Zugdidi, male, 36-65, pro-ruling party

The opposition’s actions irritate the ruling team’s most ardent supporters, which includes approximately a third of all pro-ruling party participants. They claim that the opposition profits from the circumstances created by the pandemic, fails to recognize the critical nature of the situation, and purposefully fails to agree during the negotiations (i.e., fails to sign the negotiation agreement), while the ruling party must do everything. According to this group, the opposition should not have the authority to put the government in a position where they must explain themselves. In their opinion, the opposition’s demand for not only the release of Giorgi Rurua and Nika Melia, but also for early elections, is illegal. This group of participants believes the government should take harsher measures against the opposition, including strict, far-reaching laws to allow the government to take a firmer approach to the protests, which often continue into the evening after the start of the mandated curfew put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic. They believe that international organizations should be critical of the opposition, which has stymied the negotiations. These participants believe that the establishment of stability in the country at this stage is possible only through authoritarian methods. The participants see placing full responsibility and power in the hands of the ruling team as the way out of the situation.

Democracy does not mean that the opposition should not be punished. The government should be stricter.

Kutaisi, male, 36-65, pro-ruling party

Finding 2

Participants’ mistrust and disappointment with election campaigns over the years has led them to view parties’ pre-election activities as ineffective and insignificant. Parallels between the 2020 pre-election campaigns and previous campaigns contribute to this view.

General perceptions about the 2020 election campaign are negative. The vast majority of participants from both political groups note that, based on the past activities of the candidates and due to pre-established attitudes towards them, their vote was decided before the campaigns began. Participants are likely to be reluctant to acknowledge that they may have been affected by the election campaigns, as in their experience these processes are associated with unfulfilled promises, misuse of administrative resources, and “bribery.” The overwhelming majority of discussants believe that campaigning is ineffective. The fact that various parties/candidates’ pre-election activities bear a resemblance to one another leads discussants to doubt the credibility of the promises made. They deny that campaigns have any influence, assuming that politicians will only tell people what they want to hear in order to gain their votes. The fact that pre-election campaigns went exactly as predicted by participants leads to skepticism about political figures’ trustworthiness and honesty during the pre-election period.

No one believes that whoever says what he says will really do it. Simply, you either trust the person, or you do not trust. The previous pre-election campaign, no matter who it was for, did not affect me.

— Tbilisi, female, 36-65, pro-ruling party

Focus group participants noted less activity, as compared to prior elections, on the part of both the ruling and opposition parties during the 2020 election campaigns. Participants have a vague idea of both the content of the election campaigns and the programs presented by the parties. Many participants claimed that the parties did not have programs submitted, although further discussion revealed that they did not have information on existing programs by specific parties. Participants were less engaged in actively seeking information about parties or candidates during the pre-election period; thus, they are mostly recalling activities that were covered on television or posted on social media.

As for the sources used by the participants to obtain information about political parties during the pre-election period, participants named television, the internet, banners, posters and flyers, and direct communication (meetings held by party leaders and door-to-door visits by party coordinators). The conversation revealed that the participants of the study, especially the residents of the regions, mainly refer to public posts on social networks published by friends, political figures, and media outlets when speaking about online information sources.

Looking at the main picture of the pre-election campaigns, it was identical to the last 30 years. Some pseudo-pathetic phrases that do not really mean anything.

Batumi, male, 18-35, pro-opposition

Finding 3

When reflecting on the 2020 elections, opposition supporters list numerous serious violations from Election Day. Ruling party supporters categorically deny intimidation and pressure on voters occurred, characterizing such cases as “influence.”

Partisan allegiances shape participants’ views of Election Day and the results. Participants supporting opposition parties cite specific examples of election violations, including cases they have witnessed and/ or experienced themselves. These include many cases of pressure, intimidation, vote-buying, misuse of administrative resources, the activity of criminal authorities (“thieves-in-law”3), votes cast for a particular party/candidate for fear of losing one’s job, and carousel voting (casting a pre-filled ballot in the ballot box and taking a new, unfilled ballot from the polling station). Many of these participants stated that the misuse of administrative resources was an issue in the 2020 elections. They cite pressure from criminal authorities, coordinated actions of police officers, involvement of district heads of police and members of the municipal government in election campaigns, and mobilization of civil servants. Specific isolated examples are sufficient evidence for them to conclude that the elections were not free, fair, and transparent, casting doubt on the legitimacy of the election results.

When the government realized that they were losing, they involved ‘thieves-in-law’. There have been cases when thieves-in-law intimidated people to vote for [Georgian Dream].

Zugdidi, male, 18-35, pro-opposition

These participants sarcastically answer the question about free, transparent, and fair elections. The vast majority of them believe the election was rigged, as evidenced by election violations and irregularities in the CEC, which they believe is another reason to doubt the credibility of the results and proves that the elections were rigged during the counting process.

Government told people: come and vote for me once, and I will give you 1 kg of sugar and 1 kg of pasta, and these people agree, 1 kg of sugar is really important for them at the moment.

Borjomi, female, 18-35, pro-opposition

Representatives of the criminal authorities come up to people and say, ‘you know who to vote for’. They were trying to convince people by intimidation or pressure, or giving money to support the ruling party.

— Kutaisi, male, 18-35, pro-opposition

Participants who support the government are optimistic about the election results. They present OSCE/ODIHR findings as the primary proof that the 2020 elections were free, fair, and transparent. These participants tend to view the quiet environment in their own district and the choices made by those around them as reflective of the rest of the country, skewing their perception in favor of the government. They have confidence in the validity of their own experience, while at the same time, they are inclined to view information on violations covered on television as staged and therefore unreliable. Consequently, the generalization of the cases in their own narrow society is an argument for them that the elections were held in a calm environment, in compliance with all rules and regulations. Some of the participants consider the presence of foreign observation missions, local observer organizations, and cameras in polling stations to be an irrefutable argument supporting the credibility of the elections. In other words, they believe the election process is transparent and, as a result, this rules out the possibility of falsification of the results. For these study participants, their main argument is based on the assessment by foreign observer organizations that the election was not rigged.

I’ve seen it on TV, but it seems more staged than real. Otherwise, how can the cameraman be prepared to shoot the entire scene from start to finish?

Tbilisi, female, 36-65, pro-ruling

For some participants in this group, the existence of some “tiny” violations does not mean that the elections as a whole were held in an unfair manner and are not credible. Younger participants recall individual cases of irregularities, although they believe that these were not centrally organized and that the decisions were made at the individual level by coordinators, agitators, and activists. These discussants assume that these local party representatives, attempting to prove themselves to party leaders, endeavored to influence voters. Thus, they were not carrying out orders from the government or ruling party but were themselves the initiators. Therefore, these cases are considered pardonable. Their assertion that violations occurred on a regular basis and that “the situation was worse when Misha4 was president” demonstrates that ruling party supporters attempt to find justification for actual election violations.

When it comes to intimidation and pressure, pro-government participants are especially cautious in their choice of terms. In this regard, the situation in Tbilisi and the regions differs. Regarding the mobilization of public employees, the participants of the Tbilisi focus groups say that this is an old practice and such cases have always existed, thereby justifying the misuse of administrative resources. In the regions, supporters of the ruling party categorically deny any direct pressure or intimidation occurred during the pre-election period. It is only later in the discussion that the existence of such cases is discovered. However, these instances are still described in a milder form as “influence.” In this manner of speech, they express an attempt to justify the ruling party’s actions.

In terms of intimidation, I don’t think so. But there were some cases of influencing people, I’ve only heard.

— Borjomi, female, 18-35, pro-ruling party

Finding 4

Participants are unable to define the CEC’s exact functions and responsibilities or its role during the 2020 elections. However, they believe the CEC’s independence and neutrality are critical.

Asking about the role of the CEC causes some confusion among participants. Regardless of political affiliation, the majority of participants agree that the CEC’s role is to ensure fair elections and that this institution must be neutral and independent. Participants have difficulty describing the CEC’s functions and responsibilities, as well as its role in the 2020 elections, in any detail. According to them, the main function of the CEC is to conduct the election process properly, to count the votes, and to announce the election results.

[The CEC] must not be biased, it must be fair and must make decisions independently.

Telavi, male, 18-35, pro-ruling party

I think that the CEC should not support any party, it should be neutral.

Batumi, female,18-35, pro-ruling party

Although participants’ assessments of the CEC’s role and functions are homogeneous, views on the CEC’s neutrality are divided on party lines. Pro-government participants express that the role of the CEC in the 2020 elections was positive and that it more or less coped with the challenges it faced. When asked if the CEC is a neutral body, they answer it “should be neutral,” avoiding passing judgement on the institution’s independence in the present. At the same time, they state that the neutrality of this institution is as necessary and important as the courts in general to improve the election process. Although the neutrality of the CEC is associated with the independence of courts in most discussants’ speeches, when probed further, only a few of them can describe the link between the two institutions. Those participants recognize the close relationship between the judicial system and CEC functionally and assert that CEC reforms will be successful only if impartiality of the courts is first ensured.

Judicial reform is the foundation. If the court is independent everything will be settled.

Kutaisi, male, 18-35, pro-opposition

Whoever is the chairperson of the Central Election Commission should be independent. He/she must be the executive in order to establish justice.

— Kutaisi, male, 18-35, pro-opposition

Pro-opposition supporters have a more negative view of the CEC. They do not perceive it as an independent body, because they believe that this institution played a key role in rigging the elections. The focus group participants believe that the CEC is under the influence of the government, is a “puppet” in the hands of the ruling party, and is staffed by unprofessional individuals who counted the ballots in the interests of the Georgian Dream and Bidzina Ivanishvili. They believe the CEC is a subdivision of the government and that it arranged the desired result. This group of participants is most concerned with the irregularities observed during the 2020 elections. When asked to assess the role of the CEC during the elections, the first associations of discussants are specific cases of inaccuracies in its work. Thus, they have a tendency to evaluate the overall performance of this institution based on its actions in the most recent election.

In general, they (the CEC) play the biggest role, they should not turn to any party. Their role in the elections is the elections to be fair. They must be apolitical. They collaborated with the government in the 2020 elections and that’s why the ruling party won.

— Zugdidi, male, 18-35, pro-opposition

Finding 5

Most participants are unaware of, or have only a limited understanding of, the reforms put in place prior to the 2020 elections. According to participants, this is a communication issue, and such information should be delivered to voters more effectively.

Participants find it difficult to recall the electoral reforms implemented before the 2020 elections. A maximum of one to two participants in each group mentioned changes to lower the electoral threshold to one percent, merge some constituencies, and move to a more proportional parliamentary system. Participants express a desire to have more information about the electoral reforms that have been implemented. Supporters of both the ruling party and the opposition consider the government to be responsible for the incomplete and infrequent communication in this matter.

Electoral reforms do not really come first for me. The first step is to get rid of the COVID and breathe. For children to get a normal education, second, economic issues, and then politics and elections.

Tbilisi, female, 36-65, pro-ruling party

Participants, regardless of political affiliation, see the need for reforms to uphold the principles of democratic elections, to ensure fair elections, and to ensure the transparency of the electoral process. Supporters of opposition parties place great importance on electoral reform. For them, the most desired outcome of the negotiations, or early elections, makes no sense if there are no electoral reforms. By contrast, supporters of the ruling party believe that at this stage other issues are more important than the electoral reforms. For example, developing strategies to address the COVID-19 pandemic and tackle economic challenges were a higher priority for this group.

Although the majority of participants believe that electoral reforms are important and relevant for the country, participants find it difficult to name the specific changes that need to be made. Reform of the CEC, amendments to the rules for electing the CEC chair, and the use of election technologies are some of the issues that have been raised in this regard. Participants’ recommendations on the named topics do not represent an established and thoughtful position. Their recommendations are general and do not include a specific explanation of what needs to be done and how. Participants find it difficult to describe specific steps or the structure of reforms. For example, in the case of reform of the CEC, they talk about training staff and recruiting non-partisan members of the election commission to raise their level of professionalism. Participants underline that the main priorities of electoral reform are to protect the vote of the electorate and to hold democratic elections in a free and fair environment, although ideas about the structure of the reforms are vague.

Priorities in terms of reforms should be: protection of rights, justice, transparency; vote protection, accountability mechanism.

Zugdidi, female, 36-65, pro-opposition

Conclusion

The focus group discussions underscored discussants’ dissatisfaction with the political situation in the country at the time and their desire for resolution of the crisis. Participants seek stability and peace, as well as effective governance and responsiveness to top citizen concerns, especially on economic issues. The focus groups highlighted the public demand for the ruling party and opposition to engage in dialogue with one another.

When discussing the 2020 pre-election environment, most discussants recall cases of election violations. Despite the fact that the discussants attribute responsibility differently based on their political sympathies, they see room for improvement for both parties’ election campaigns and prevention of irregularities in the pre-election period. The 2020 election campaigns were seen as similar to those of past elections, and thus are perceived as neither trustworthy nor effective. Discussants would prefer candidates communicate with them face to face in a more honest and open manner. This reflects a demand for parties to make realistic campaign promises and to be held accountable for their realization after taking office.

Although research participants acknowledge the importance of free, fair, and transparent elections, the discussion revealed many participants’ inability to articulate concrete steps for overcoming inaccuracies and violations both during the pre-election period and on Election Day. Their representation of electoral reforms is generally vague, although in some cases, participants mention specific reforms, such as use of election technologies and changes in the structure of precinct election commissions and the CEC. Participants list the neutrality and independence of the CEC as the main priorities; however, the unstructured manner of the conversation shows that participants have less knowledge and information about how this can be achieved. Ultimately, Georgian policymakers must implement measures to increase public confidence in electoral outcomes.

Appendices

Appendix A: Methodology

Focus group discussions were held in six locations throughout Georgia, including participants from the capital and seven regions. Although the initial design implied that the research would cover all 10 regions of the country, due to the limited number of groups (24), it was not possible to include Kvemo Kartli, Mtskheta-Mtianeti, RachaLechkhumi, and Kvemo Svaneti discussants in the study. The regions of the country represented in the study aside from Tbilisi include Adjara, Guria, Samegrelo, Imereti, Samtskhe-Javakheti, Shida Kartli, and Kakheti. Four focus groups separated by age and political views were conducted in each location.

Overall, 192 discussants participated in the study. Gender balance was maintained in most groups, with four male and four female participants represented in most of the focus groups. Please reference the table below, which gives detailed information on the composition of the focus groups.

Focus groups were conducted face-to-face in compliance with Georgia’s COVID-19 regulations and IRI’s security protocols for in-person activities. IRI staff observed 14 of the focus groups. All participants, including alternates, have been compensated for their time and participation.

The focus groups lasted between 90 to 150 minutes each. Participants were encouraged by the moderator to express their views openly and freely, even if they differed from the attitudes of the other participants in the group. For the most part, participants were actively involved in the discussion. Focus groups were generally conducted in a peaceful environment. Participants joined the conversation voluntarily and without coercion, and in some cases, debates took place.

Participants were selected using the screening questionnaire included in Appendix C. The main selection criteria for the discussants were as follows:

- Discussants had completed secondary education or higher.

- Participants were recruited from various neighborhoods within the target cities.

- They expressed a strong desire to learn about and share information about national, regional, and global issues and events that they believe have an impact on their lives and the future of their society.

- Participants agreed to engage in an open discussion of various political topics.

- Participants in the same focus group session did not know one another.

- Discussants had not participated in a focus group or in-depth interview study in the past six months.

Appendix B: Focus Group Discussion Guide

Focus Group Discussion Guide (Georgia Spring 2021)

Notes for Moderator:

The moderator should emphasize that it is important that the participants speak freely and openly. The participants should understand that their comments, both positive and negative, will be appreciated.

This discussion guide is not a script; rather, the main purpose of this guide is to familiarize the moderator with the questions and issues that we would like to see addressed during the focus groups and to recommend a general order and flow of the topics to be discussed.

The focus groups themselves should be as free and spontaneous as possible. So long as the moderator investigates the issues in this guide, he/she is free to combine questions, change questions, omit questions that do not seem to be working and add questions in response to interesting trends as they become apparent. The moderator may also prompt the participants if they need help getting started. However, the moderator should let the participants respond spontaneously initially.

The moderator should aim to get specific and detailed answers through probing and follow-up questions, and by encouraging a true exchange of views among the participants. It is important that the moderator conduct a group discussion, not a group interview.

Please keep the following study objectives in mind throughout the group discussions: Gather deeper insights into various political and social issues, such as views on national politics and the economy, the 2020 parliamentary elections, political and electoral processes, and avenues for reform, and the impact of COVID-19. The participants recruited for this study come from various cities, and the 24 sessions are further segregated by age groups (18-35; 36-65) and political views (pro-ruling party; pro-opposition).

I. INTRODUCTION (2 MINUTES)

Introduction of moderator and participants

- Consent: My colleagues have already gone over the consent form with you. Do you still have any questions for me?

- Explanation of purpose of group: We wish to learn about your thoughts on a variety of political and social issues that affect our country.

- Explanation of the “rules” of the discussion:

- Speak freely and openly.

- Be critically-minded – constructive criticism and negative assessments are as important as positive comments and praise.

- Try not to talk all at once.

- Be as specific as possible with concrete examples whenever possible.

- Mobile phones: Turn off

II. WARM-UP (5 MINUTES)

Before we start discussing the main topics, let’s start with introducing ourselves to the group. Please share with us your first name, your occupation, your hobbies, and tell us about your family.

III. GENERAL OVERVIEW OF POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC SITUATION AND IMPACT OF COVID-19 (APPROX. 15 MINUTES)

Objective: To understand participants’ overall assessment of the political and economic situation in the country, including perceptions of the government’s actions to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Moderator: Today we will discuss some of the most pressing issues facing our country these days.

- To start off, how has the COVID-19 pandemic affected you? (Moderator: if multiple issues named, probe: What would you say the biggest challenge is?)

- Have you received any assistance from the government related to COVID-19? If yes, in what form? And from what level of government? And was it sufficient or insufficient and why?

- How has your view of the government’s pandemic response changed in the past 12 months? If it has changed, what influenced this shift in your opinion?

- How would you assess the current economic situation in the country?

- What are the main factors that influence your assessment?

- How does the economic situation affect your household?

- Who bears responsibility for creating the economic situation we have now? Who is responsible for addressing economic problems in the country?

- What is your opinion of the current political situation in the country?

- What are the main factors that influence your assessment?

- Who bears responsibility for creating the current political situation?

- Who is responsible for solving the political challenges facing the country?

IV. 2020 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION CAMPAIGN (APPROX. 20 MINUTES)

Objective: To understand participants’ perceptions of the 2020 election campaign and the participating parties.

- Thinking back to last fall, how would you assess the 2020 pre-election period?

- What were your expectations for the 2020 pre-election period? Were your expectations met?

- How would you describe the environment in which the 2020 election campaigns took place? Did you or any of your friends or family experience any forms of pressure or intimidation in relation to how you would vote in the election? If so, please provide details.

- Are you aware of any cases of misuse of administrative resources during the campaign? By this I mean instances when public officials or employees mix official business and campaigning, or when they use their public position, connections, or public resources for the benefit of their party’s campaign.

- If yes, can you tell me a bit about the case or cases you are aware of—what happened and where and who was involved.

- If yes, how did you find out about such cases (Moderator: look for direct witnessing, word of mouth, social media, traditional media etc.)

- If yes, how do feel about such cases: are they surprising to you or not, and why?

- Among the political parties participating in the 2020 parliamentary elections, were the available choices sufficient? Why or why not?

- Several new parties competed in the 2020 parliamentary elections. Do you believe there is still a need for new parties or new faces in Georgian politics? Why or why not?

- Which, if any, interests are not represented by the existing political parties?

- How relevant were the political parties’ campaign platforms to the issues that are important to you?

- How did you get information about candidates and political parties? Did you feel that you had enough information about the candidates/parties to make an informed choice? Was this information trustworthy? If not, why not?

- What information would you like to know about candidates/parties?

V. ELECTION DAY AND RESULTS (APPROX. 25 MINUTES)

Objective: To understand participants’ experience on Election Day and their perceptions of the election results and subsequent events.

- What is your assessment of the events on Election Day and the election results?

- Did you experience or witness any instances of pressure or intimidation in an attempt to influence your vote? Did your friends or family experience this?

- If yes, can you tell me a bit about the case or cases you are aware of—what happened and where and who was involved.

- If yes, how do feel about such cases: are they surprising to you or not, and why?

- Did you trust or distrust the official results of the 2020 parliamentary elections?

- If trust, what was the reason?

- If distrust, what was the reason?

- Did you experience or witness any instances of pressure or intimidation in an attempt to influence your vote? Did your friends or family experience this?

- Do you believe the 2020 parliamentary elections were free, fair, and transparent?

- Which factors inform your assessment?

- Are you aware of local election observation organizations’ assessments of the 2020 elections? If so, do you trust their assessments?? Why or why not?

- Do you consider the opposition parties’ decision to boycott entering the Parliament justified? Please explain your response.

- To what extent do you agree with the opposition’s demand to hold snap elections? To release Giorgi Rurua and Nika Melia? Please explain the reasons for your support (or lack thereof) in both cases.

VI. THE CENTRAL ELECTION COMMISSION (CEC) (APPROX. 10 MINUTES)

Objective: To gain a nuanced understanding of perceptions of the Central Election Commission and its role in ensuring free and fair elections in Georgia, particularly in the context of the 2020 parliamentary elections.

- What do you understand as the role of the Central Election Commission (CEC)? The head of the CEC?

- Do you believe the CEC is a neutral body? Why or why not?

- What is your opinion of the CEC’s actions in the 2020 parliamentary elections? Of the work of the head of the CEC?

- How could the CEC be reformed to improve the way that Georgian elections are run, if at all? (Moderator: if multiple issues named, probe: what should be the top priority for reform?; If increased transparency or other intangible changes named, probe: what concrete changes would need to take place to achieve that?)

VII. NEXT STEPS: ELECTION REFORM AND WAYS OUT OF THE CRISIS (APPROX. 25 MINUTES)

Objective: To gain insight into public perceptions of the ongoing negotiations between the ruling party and opposition, prospective electoral reforms, and the desired path forward for the country.

- What are your perceptions of the negotiations between the ruling party and opposition parties?

- Who is playing a constructive role in the negotiations, if anyone? Who is to blame for the breakdowns in negotiations?

- In your view, is compromise between the two sides an acceptable outcome? In your opinion, will both sides need to compromise to some extent, or will only one side have to concede on some of their demands?

- In your mind, are there red lines, i.e., subjects where no compromise should take place? If so, what are those subjects?

- From your point of view, what are the best possible outcomes that could result from the negotiations?

- What steps do you recommend to overcome the current political situation in the country?

- How have the events of the past twelve months impacted your trust in Georgian elections? In the overall political system?

- How relevant is the issue of electoral reforms for you personally? To what extent does the country need electoral reforms?

- If further electoral reforms are needed, in your view, what should be the top reform priorities?

- What are your perceptions of the electoral reforms passed in 2020 prior to the parliamentary elections? Did those reforms have a positive or negative effect, or none at all, on the conduct of the parliamentary elections?

VIII. WRAP-UP (APPROX. 5 MINUTES)

Objective: To elicit open feedback to potentially raise points of importance for participants that were not addressed earlier in the discussion.

Today’s discussion was meant to look your perceptions of national politics and the economy, the 2020 parliamentary elections, political and electoral processes and avenues for reform, and the impact of COVID-19. I have given you many different aspects of these topics to discuss. But there may be other aspects that I did not think about that may also play a role. Is there anything else that someone who wants to fully understand these issues should know?

Appendix C: Screening Questionnaire

Footnotes

- The FGDs were conducted in Georgian. Therefore, quotes cited in this report were translated from Georgian to English and have been minimally edited to ensure clarity. As much as possible, the English translations preserve the syntax, word choice, and grammar of the Georgian speaker.

- https://www.iri.org/resource/new-poll-amid-political-crisis-georgians-show-concerns-over-economy-and-covid-19

- The term “thieves-in-law” refers to high-level, professional criminals in organized crime in the post-Soviet states and diaspora communities.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, President of Georgia from 2008 to 2013.