Introduction

The International Republican Institute (IRI) defines a mentorship as a relationship in which a person or organization provides intentional, ongoing support to other people or organizations with fewer or different experiences, to build their capacity, motivation and professional opportunities. The purpose of this guide is to help mentors and mentees better understand their roles and responsibilities in the mentorship process, as well as to provide tips and tools to set mentorships up for success. This guide is applicable to both individual mentorships and mentorships between organizations.

As part of this guide, IRI will provide an overview of the mentorship process:

This guide was developed by a number of teams at IRI, providing a global view of best practices and lessons learned from mentorships within the civil society sector. Specifically, the guide was developed by the following teams.

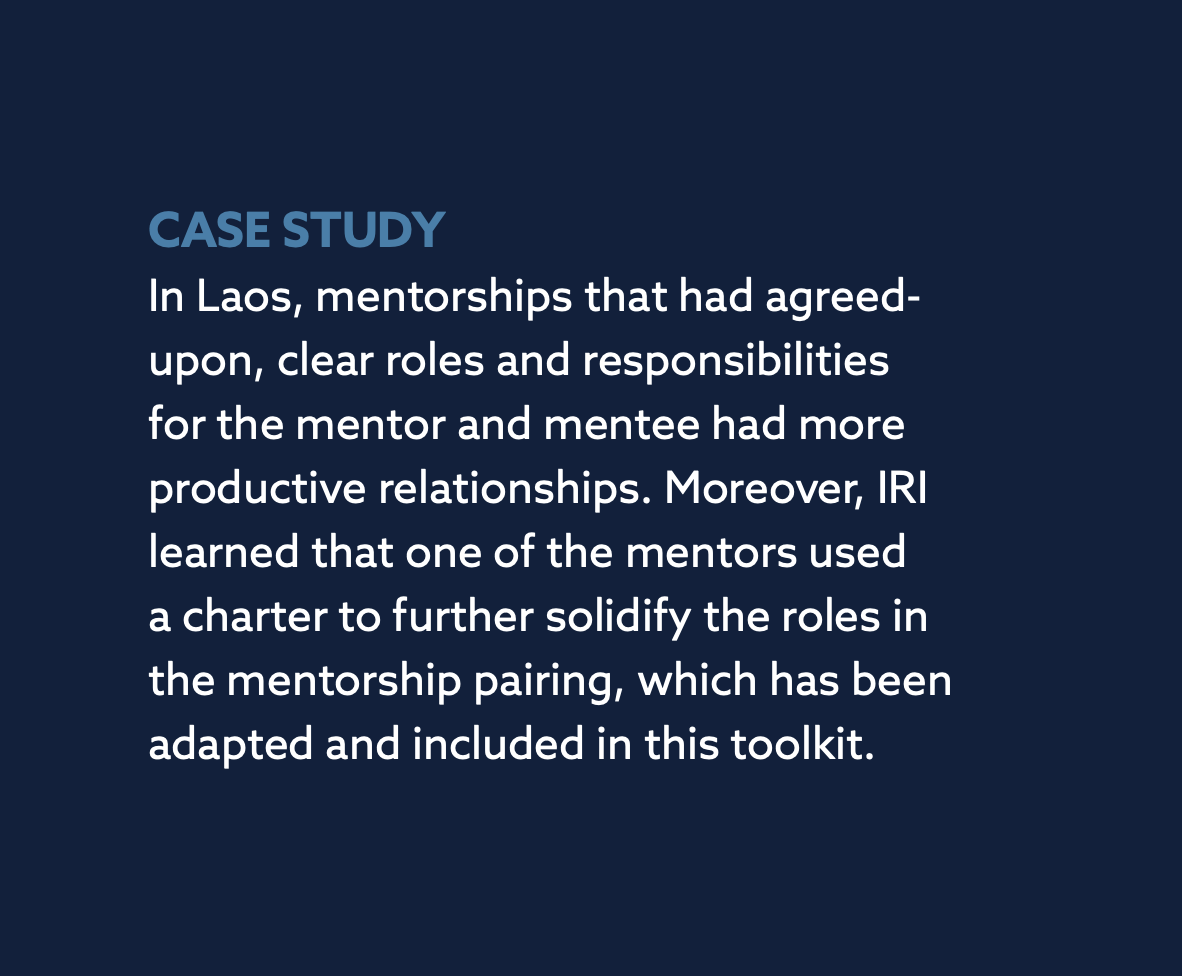

Laos

IRI implemented three iterations of mentorship programming with Lao civil society groups. In the current iteration of IRI’s mentorship program, IRI utilized a peer-to-peer learning structure and developed a mentorship curriculum and toolkit focused on sharing tools for funder outreach, capture planning and proposal development.

Panama

IRI trained and mentored civil society organizations (CSOs) in Panama on improving their organizational capacity to lead programs, connect with funders and partners, and manage operations. IRI evaluated each CSO’s strengths and weaknesses through a baseline civic-organization assessment tool (COAT), the results of which the institute used to design and lead tailored trainings to improve each CSO’s organizational capacity.

Cuba

IRI used the mentorship process to support civil society organizations and activists who promote human rights in Cuba.

The Evaluation and Research Team

This team leads thematic, cross-cutting and donor priority evaluations and research; produces thematic technical guidance to help teams understand sound program-design principles; and tests program theories that result in more innovative and effective projects. In July 2020, IRI conducted an “Evaluating Democracy, Rights and Governance (DRG) Effectiveness (EDGE)” assessment of previously completed IRI programming in Laos, focusing on how sustainability theories of change (TOCs) function in practice through mentorships.

Understanding Each Role

Being a Mentor

A mentor is an individual — whether local or international — with more experience in a given professional field, who helps someone with less experience (the mentee) to grow professionally. Based on IRI’s assessment of mentorship best practices, there are three key things mentors need to do to ensure a successful mentorship. These include sharing relevant experiences and expertise, providing access to new and relevant resources, and serving as a sounding board for their mentee. More details about each aspect can be found below.

A mentor is:

Supportive

A mentor’s role is not to instruct or guide, but rather to offer experience and act as a sounding board, supporting mentees while they work through issues. This is done, in part, through sharing of experience. As such, mentors should be prepared to share stories about their past experiences, both good and bad, with their mentees to help them develop their own solutions and ideas. This can also include offering objective insights as an independent third party and introducing new ideas, techniques and stakeholders. In lieu of dictating the “correct” way to achieve a goal or fix a problem, the mentor should illustrate what they did in a similar situation, allowing the mentee to decide for themselves if that approach will work in their individual context.

Mentors can offer different types of support — technical and sector specific, or structural and organizational. Mentors should also have expertise in organizational or technical areas relevant to the mentee’s mentorship goals. For example, if a mentee wants to become a leading voice for promoting women’s legal rights, it may be beneficial for the mentor to have experience developing gender-equality policy so they can coach the mentee on relevant technical skills, such as interpreting new laws and conducting research-based advocacy.

With that said, if the mentee is seeking to develop their capacity for leadership, management or other soft skills, mentors do not need to be from the same sector to provide relevant expertise. For example, if the goal of the mentorship is to improve the mentee’s ability to be a better manager of a CSO, the mentor can be from any sector as long they are willing and able to coach the mentee on developing their managerial skills.

A Resource

Mentors have an already-established network of peers and professional contacts that can be leveraged to make connections for their mentee. Mentors helping their mentee establish relevant, meaningful relationships is often one of the most important results of a mentorship. For instance, in contexts in which program implementation and safety are greatly affected by relationships with government officials, helping mentee organizations establish these connections may increase their chances of success. Additionally, mentors can introduce mentees to potential partners and collaborators, another key element of networking. In some cases, connections made through mentor introductions would have taken years to build without them. Mentors have already built trust and credibility with professional contacts and partners. As such, these collaborators may be more willing to provide support or funding to organizations or individuals for whom the mentors have vouched or have trained themselves.

In addition to relationship building, connecting mentees with other sources of knowledge and professional development opportunities — such as regional conferences or associations, or access to resource libraries — is a key component of being a successful mentor. Individuals being mentored are looking for advice and guidance, but it is unlikely they will find one mentor with all the answers. If a mentor does not have the skillset is to provide their mentee with the feedback and guidance they are seeking, they can connect their mentee with someone from their network who can assist them.

A Sounding Board

In an effective mentorship, the mentor should provide constructive feedback to their mentee on a regular basis. Constructive feedback is defined as providing useful comments and suggestions that contribute to a positive outcome, a better process or improved behaviors. Constructive feedback provides encouragement, support and direction to the person receiving it. When providing constructive feedback to a mentee, some key things a mentor should keep in mind include:

- Focus on observation: Constructive feedback should relate to what can be seen or heard about the mentee’s behavior, rather than making assumptions and interpretations.

- Focus on things that can be changed: Constructive feedback should be about things that a mentee can change and improve, rather than things that are out of their control.

- Acknowledge what is working: Constructive feedback should acknowledge the successes of the mentee in order to reinforce positive habits.

Understanding of Their Mentee

Mentors should be willing to grow and learn with their mentee. To do so, mentors should take the time to get to know their mentee at the onset of their relationship. Mentors can then tailor their guidance to the mentee’s lived experiences. Keeping an open mind and treating their mentee with respect will foster a productive and successful relationship.

Being a Mentee

IRI defines a mentee as a person or organization who receives ongoing support from another person or organization with more experience to build their resources, motivation and/or professional opportunities. Based on IRI’s assessment of mentorship best practices, IRI has identified key behaviors in which mentees need to engage for a successful mentorship. These include being motivated, embracing feedback and managing up.

A mentee is:

Motivated

While mentorship is not costly for mentors, they are giving their time, resources and connections to this relationship. As such, it is important that mentees respect the mentorship process and take it seriously. A mentee needs to be motivated to take part in a mentorship, and they need to convey that enthusiasm and commitment to their mentor. Mentors often have less incentive than the mentee to participate in the mentorship. Therefore, to keep mentors engaged, it is important to be energetic, organized and focused, attend planned meetings and follow up on processes. A mentee should be able to contribute to the mentorship in order to build a genuine relationship with the mentor. For example, a mentee should take the initiative to reach out to their mentor and set up meeting or call times.

Furthermore, mentees need to recognize that hard work and sacrifice pay dividends down the road. Mentors are not there to do the work for the mentee; rather, they are there to support the mentee in doing their work better. For example, if a mentee would like help writing a proposal, they should have a draft ready for their mentor to review during their next meeting.

Receptive to Feedback

One of the fundamental purposes of a mentorship is for the mentor to provide insight to the mentee, which can be received in the form of constructive feedback or guided discussion. While constructive feedback may be useful in the review of a proposal or press release, in many situations a mentor may offer guiding questions that walk the mentee through a problem or challenge. The mentee should always keep in mind that the mentor’s goal is to help their mentee. Mentors would be doing their mentees a disservice if they did not provide honest, sometimes critical, advice. Mentees must be open to being coached and stay receptive to the things their mentor tells them. Similarly, reacting in a defensive manner may discourage mentors from providing helpful feedback in the future.

Managing Up

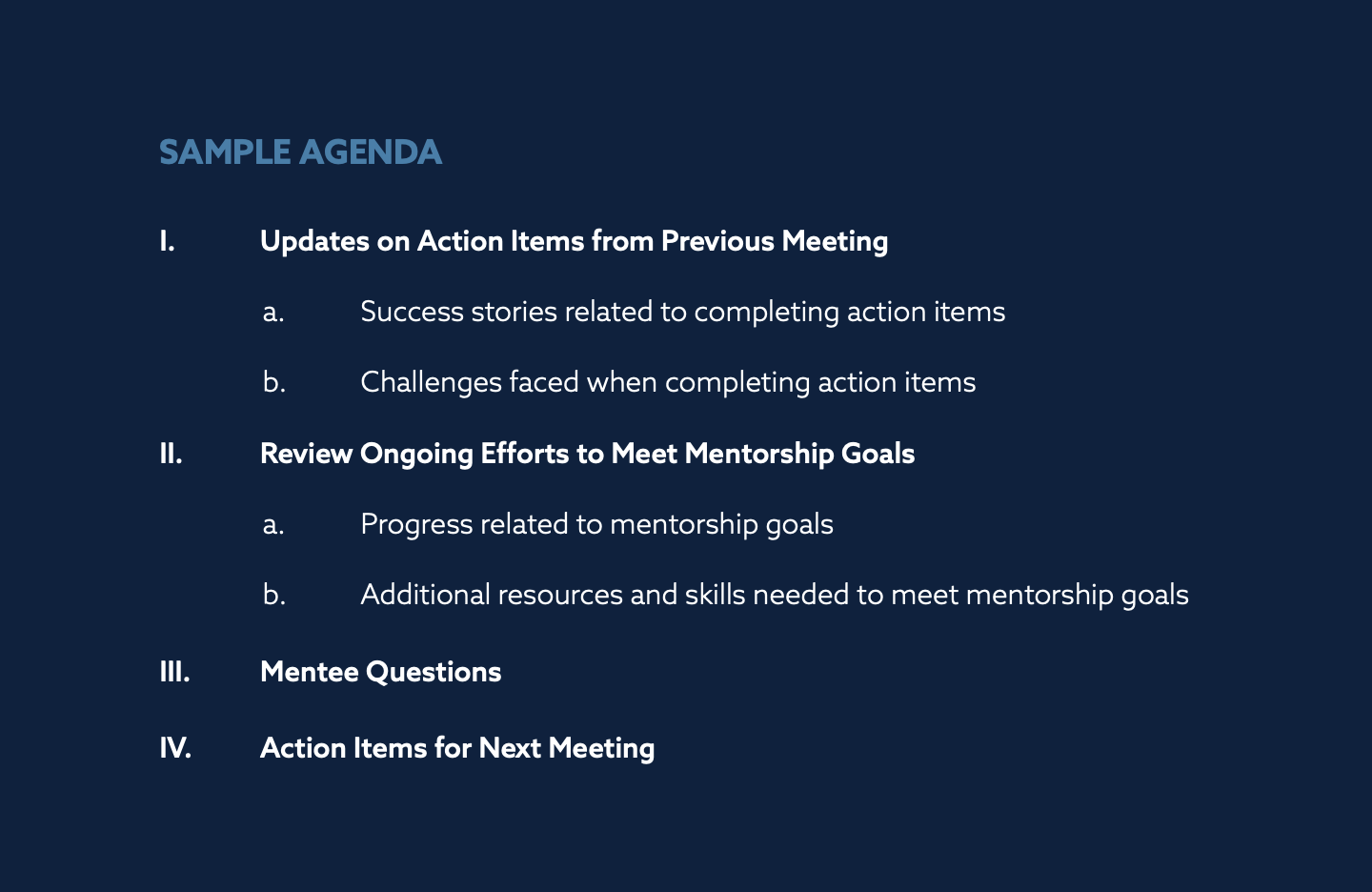

Mentees must learn to manage up — that is, to help their mentor guide them. One of the most important, and easiest, aspects of managing up is for mentees to attend each meeting with an agenda to ensure targeted feedback and advice. As such, mentees should have a clear idea of what they want to improve upon or achieve within the mentorship program — and possibly an idea of how to accomplish these goals. This can be developed in consultation with the mentor, but it is important that this is established at the outset of the program. Following a meeting structure, such as the agenda below, will ensure an efficient and productive use of time.

It can be tempting for mentees to reach out to their mentor every time a question arises, especially if the mentor has agreed to make themselves available outside of scheduled sessions. However, mentees should limit the number or times that they reach out to their mentors for the big things and should make a list of the smaller questions that come up to ask at the next session. Holding off on smaller questions until regularly scheduled mentor meetings not only shows the mentor that the mentee respects their time, but also forces the mentee to put things into perspective and focus on what is important.

Empowered

Mentees should feel empowered to leave a mentorship relationship that is not beneficial to their growth or the growth of their organization. If a mentor is unable to fulfill their originally agreed-upon expectations or is no longer a productive mentorship partner, mentees should leave this relationship and seek a different mentor. It is important to note that not all mentorship matches will be conducive to long-term partnership. If this is the case, mentees should reflect on what is needed in a new mentor and what changes are needed for a successful mentorship relationship.

Setting the Mentorship Up for Success

IRI programs have demonstrated that formal mentorship relationships are more successful when clearly defined expectations and goals are outlined from the onset of the relationship.1 Based on IRI’s experience implementing mentorship programs around the globe, the elements of a successful mentorship are:

- Trust between mentor and mentee.

- Clear mentorship goal(s) and expectations.

- Defined and agreed-upon roles and responsibilities.

- Incentives for mentor and mentee engagement.

- Balanced mentorship priorities.2

IRI has developed the following tools to maximize the potential success of a mentorship program: the “Setting Expectations” worksheet, formalized Learning Agreement and Mentorship Plan.

Setting Expectations

Before using any other tool, mentors and mentees should verbally walk through the “Setting Expectations” worksheet, which can be found as Attachment A. By sharing their expectations for the mentorship program, the mentor and mentee will have a clearer understanding of their roles and responsibilities in the relationship. The mentor should provide an opportunity for the mentee to disclose any type of information (e.g., identity or disability) that might impact their mentorship, should the mentee decide to disclose it. This understanding will play a key role in developing the Learning Agreement and Mentorship Plan.

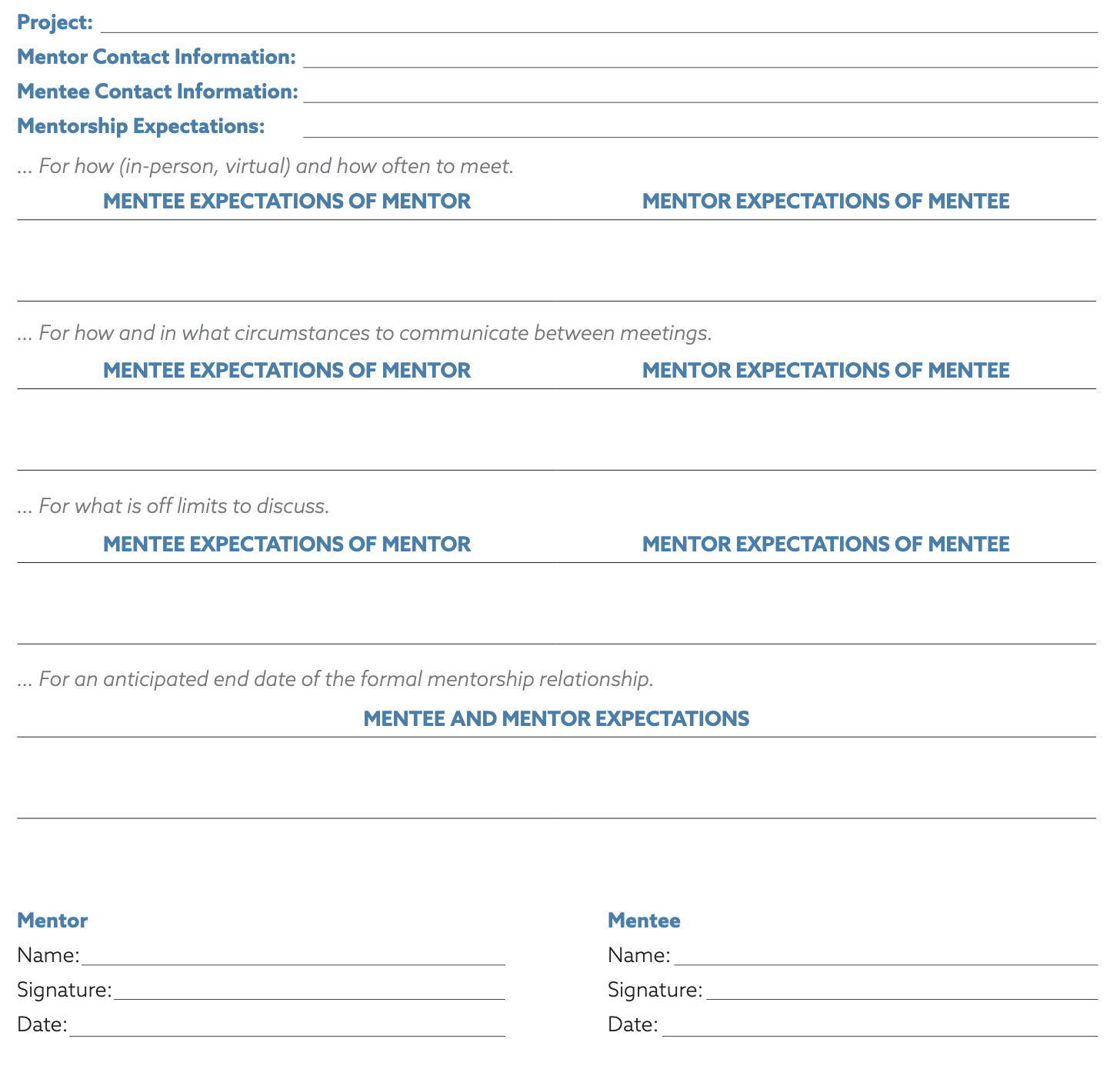

Committing to a Learning Agreement

A crucial element of expectations management, the Learning Agreement outlines mutually agreed-upon expectations for the mentorship, including time commitments and methods of communication. These expectations can be derived from the mentor and mentee’s discussion and signing of the “Setting Expectations” worksheet.

A Learning Agreement template can be found at the end of this handbook as Attachment B. However, mentors and mentees should not be constrained by the template. If needed, add additional sections to ensure the mentorship starts out with mutually agreed-upon standards.

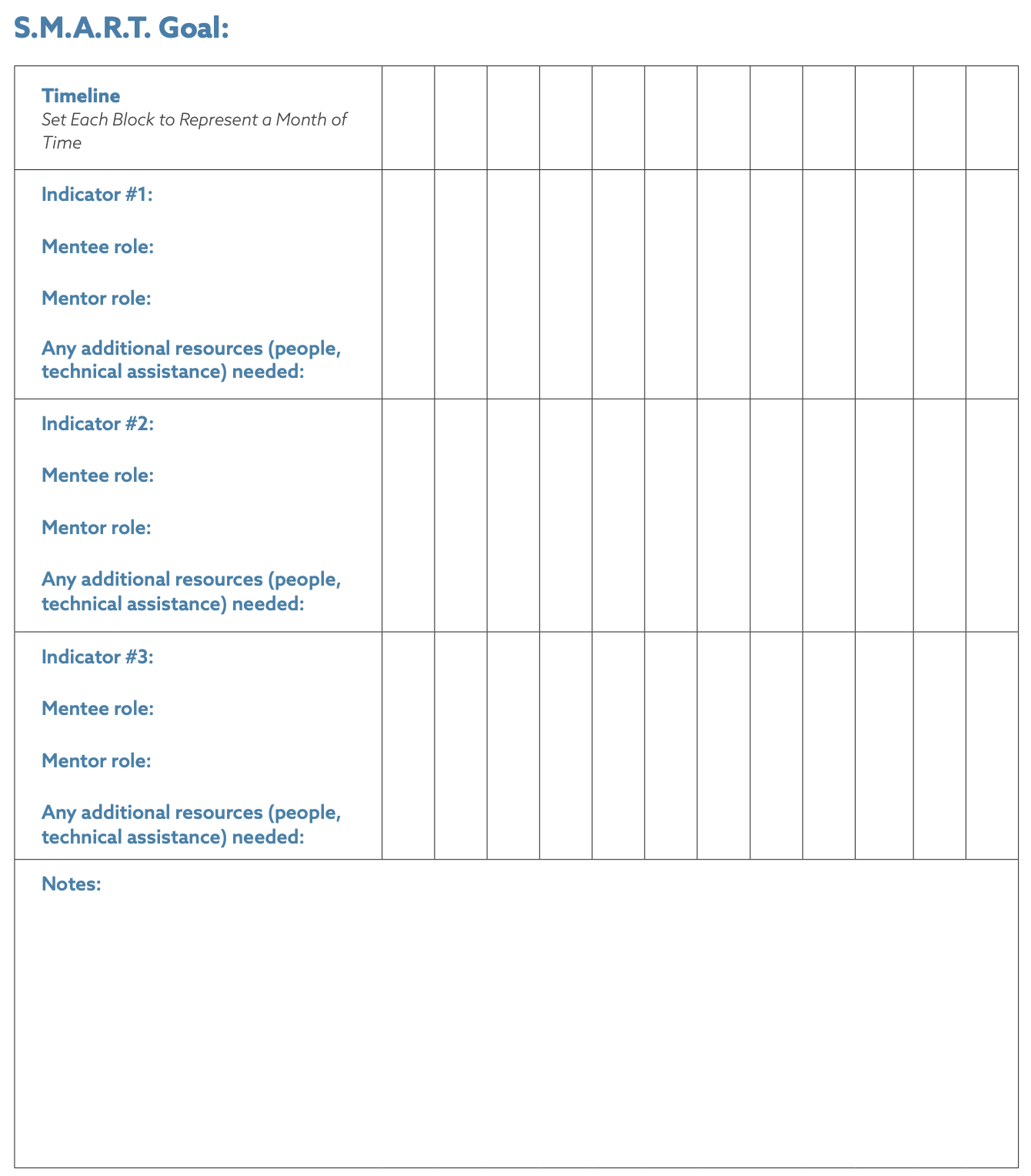

Creating a Mentorship Plan

Goal setting is a critical part of initiating a successful mentoring relationship. After setting and agreeing to expectations of the mentorship program, the mentor and mentee should co-design a structured Mentorship Plan. The plan will help the mentor and mentee define mentorship goals, identify corresponding indicators that measure progress toward meeting these goals and determine the steps needed to meet set indicators. Below are the basic steps to developing a mentorship plan, which correspond with the template in Attachment C. Following these practices will better ensure a productive, rewarding experience for the mentor and mentee.

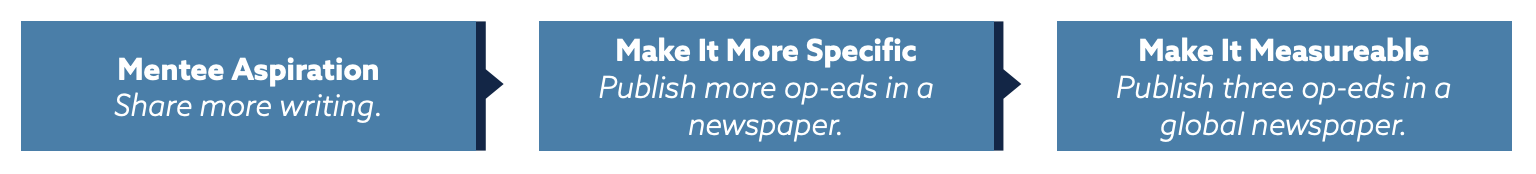

Step 1: Mentees should discuss with their mentors what they want to accomplish through the mentorship program. The output of the discussion should be one or more broad aspirations that will act as a starting point for setting more concrete goals for the mentorship program.

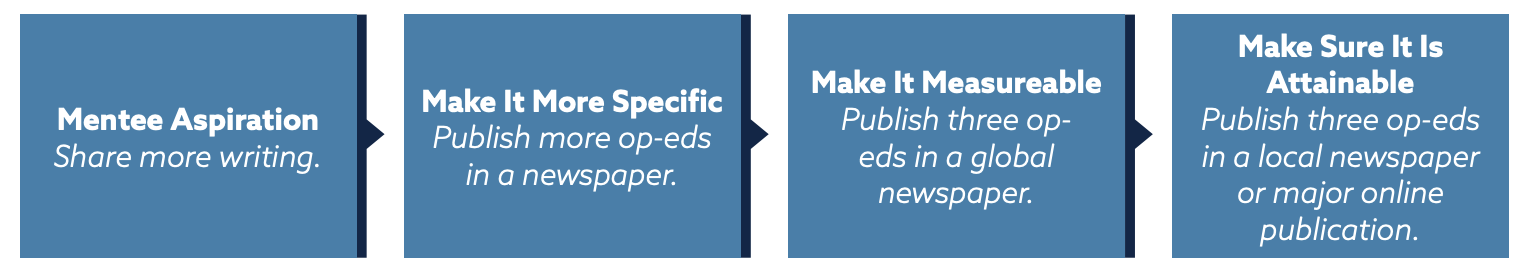

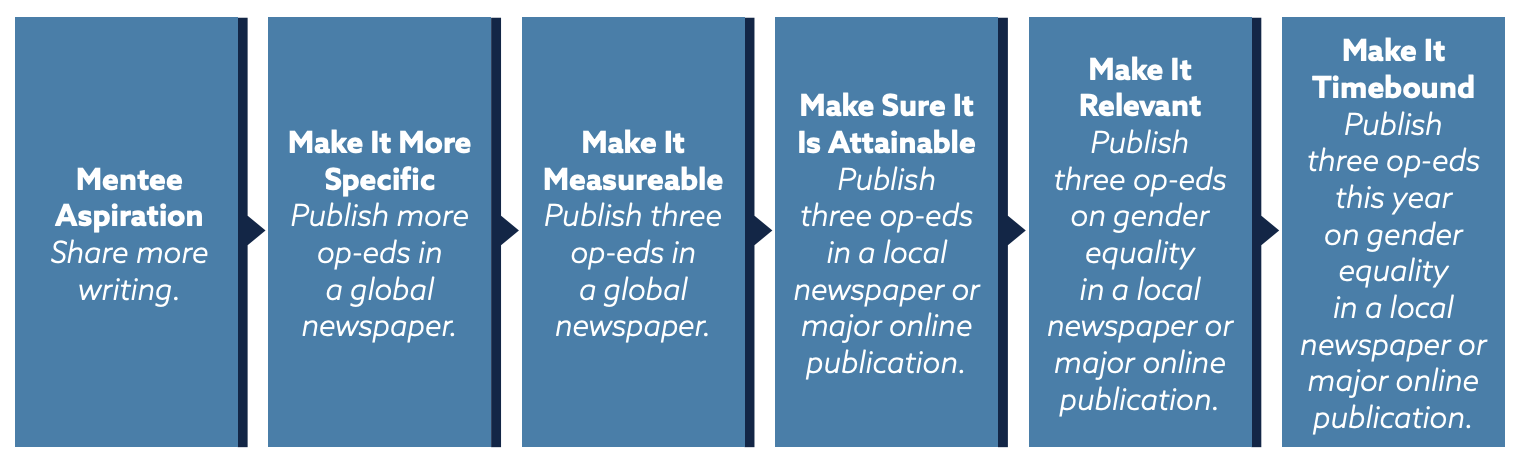

Step 2: The mentor and mentee should translate the mentee’s broad aspirations set in Step One into S.M.A.R.T. goals for the mentorship. By setting clear and actionable goals, the mentorship is more likely to be effective in achieving change.

Step 3: After outlining mentorship goals, mentors and mentees should co-develop a set of indicators, or benchmarks, to measure progress toward meeting their goals.

Step 4: On the timeline portion of the mentorship plan, mentors and mentees should work together to determine when the mentee should work toward meeting each indicator and then shade in the proposed months. The last month shaded is when the mentee anticipates meeting the indicator.

Step 5: The mentor and mentee should outline roles and responsibilities for each indicator. These roles and responsibilities can also be thought of as action items that need to be accomplished to meet mentorship goals.

S.M.A.R.T. Goals Should Be:

Specific

When goals are too vague, they are hard to turn into strategies. The more detailed the mentee can be about what they want to accomplish, the more focused the mentorship can be on setting up a plan for how to get there.

Measurable

Whatever goal the mentee wants to achieve should be measurable. Defining goals that can be measured can also be used to assess progress, which often is an important motivating factor in mentorships achieving their intended outcomes.

Attainable

Goals should be attainable. As such, mentors and mentees should consider what obstacles they might face, as well if they can overcome challenges. If it does not seem possible to overcome certain obstacles, the goal should be adjusted to be more attainable.

Relevant

Mentees should consider whether their mentorship goal is relevant. In other words, mentorship goals should align with the mentee’s values and larger, long-term professional or personal goals.

Time-bound

Mentees should set a timeframe for accomplishing their mentorship goal.

Relationship Building

Mentoring relationships need commitment and serious work from both sides. A key difference between mentoring and teaching is that unlike a student, the mentee sets the agenda for what is to be achieved, rather than the mentor or teacher. Additionally, rather than teaching, the mentor’s role is to provide guidance and support to their mentee based on their technical expertise. The mentor will have experience in certain areas and models of best practice, but the priority is to deal with the issues facing the mentee. When these issues have been resolved and learning goals have been reached, the relationship in this context will come to a successful end.

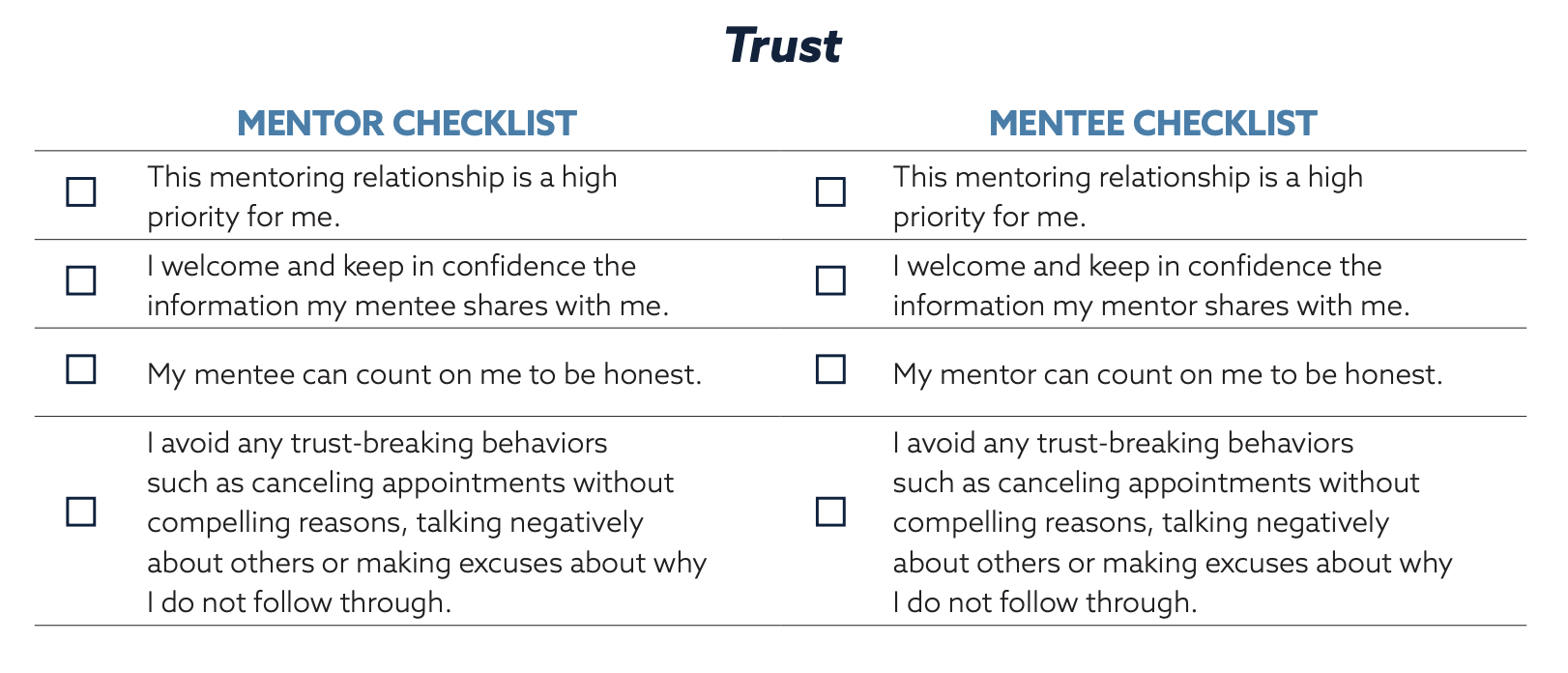

Building Trust

Over the course of implementing mentorships around the world, IRI has seen trust as a factor that can make or break the success of a mentorship. Without trust, neither the mentor nor the mentee will feel comfortable being candid asking for or sharing feedback, confident that roles and responsibilities are being taken seriously, and motivated to do the work to ensure the mentorship is successful.

Trust is one of the hardest things to establish within a mentoring relationship. Trust building requires a mutual investment, which necessitates a time commitment by both the mentor and mentee to communicate frequently and openly. Mentors and mentees should also make a concerted effort to get to know each other on a personal and professional level by actively looking for shared experiences they can both discuss and relate to, or even engage in together outside of formal mentorship meetings. The following behaviors are important to keep in mind to foster trust between the mentor and mentee.

Mentorship Structures

Mentors are likely to be further up the career ladder than their mentees. As a result, there are additional steps that mentors need to take to develop trust with a mentee. These steps include, but are not limited to:

- Guaranteeing confidentiality from the beginning. Mentors should assure their mentees that their exchanges are secure and confidential.

- Being honest and transparent. Mentors should not be afraid to get personal. By mentors sharing their career story and personal journey, mentees will be more comfortable talking about the challenges they currently face.

- Eliminating fear and intimidation. The mentoring relationship should be an open dialogue and present a time to be candid. Unless a question breaches the expectations set in the Learning Agreement, mentors should always answer their mentees’ questions and encourage them to ask more.

Behaviors that Build Trust:

- Listening proactively and with an open mind

- Sharing experiences openly

- Being vulnerable

- Following through on action items

- Actively seeking out different perspectives

- Demonstrating a positive outlook

- Honoring and respecting confidentiality

Behaviors that Impede Trust

- Interrupting others and not paying attention

- Being overly competitive

- Withholding information or being exclusive

- Not matching behavior to words

- Being closed to new ideas

- Operating from a negative perspective

- Revealing information gained in confidence

Staying Engaged

The best mentor-mentee pairings communicate frequently and openly. Traditional, in-person mentoring meetings have many benefits for mentor and mentee relationships — most notably, for developing trust. This is largely due to the importance of nonverbal communication. However, it is not always feasible or practical to have in-person meetings. For example, if the mentor or mentee is traveling — or in more recent times, if there are quarantine restrictions — in-person meetings are not an option. Mentors may also not be able to meet in person as regularly as a mentee might prefer. Virtual tools allow for continued mentoring outside of the traditional meeting setting. They should be considered an important way to ensure engagement and, in turn, a mentorship’s success.

Virtual Mentoring

“Virtual mentoring” simply refers to any mentoring activity that does not take place face to face. Tools for virtual mentoring include:

| Tool | Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Zoom | Video calling | Meetings up to 40 minutes are free. In places with internet connectivity, Zoom is a reliable, widely used service with high-quality video and sound. Includes a recording feature to save and document sessions. Can be difficult to use with a poor internet connection. |

| Google Hangout | Video calling; messaging | A completely free platform. Platform is already installed into Google tools like Gmail. Includes ability to collaborate on documents by combining Google Hangouts with Google Drive. |

| Skype | Video calling; messaging | One of the most commonly used platforms for video and text messaging around the world. Where internet signal may be weak, instead of derailing a planned meeting, the short message service (SMS) and calling services provide a backup means of facilitation. |

| Video calling; messaging | Includes unlimited real-time messaging with an internet connection. Known for its low data requirements, global recognition and accessibility. | |

| Signal or Telegram | Messaging | Includes unlimited real-time messaging with an internet connection. Includes extra security features, such as end-to-end encryption, security keys and auto-delete of chat |

| Messaging | Ideal tool if an immediate response is not needed. Sending a detailed email ahead of meeting can give the mentor and mentee time to review meeting topics so they can be prepared to discuss. |

Despite its benefits, virtual mentoring can pose some additional challenges when compared to traditional mentoring. To maximize the benefits of virtual mentoring, mentors and mentees need to be prepared to tackle challenges, including those in the chart below.

| Common Problem | Possible Solution |

|---|---|

| Communication Misunderstandings. Virtual communication is limiting for communication cues such as facial expressions or tonal inflections. This is especially true for channels such as email and audio-only calls, as mentees or mentors may be unable to correctly gauge the other’s intentions. | Overcome this communication challenge by using video chat whenever possible. This will allow mentors and mentees to see each other’s facial expressions and body language, which can help avoid misunderstandings. |

| Friction. In a perfect world, every form of technology would work all the time. However, that is not the case. Technology failures can be frustrating to both participants and possibly cause a tense relationship. | Technology problems cannot always be prevented, but one can prepare for them. Mentors and mentees should test their technology ahead of formal meetings, as well as prepare contingency plans for when technology issues arise. |

| Mentor or Mentee Non-Responsiveness. A mentor is typically someone with numerous, high-level responsibilities. That means they do not always have the bandwidth to provide substantive feedback outside of formal mentorship meetings. Additionally, a mentee who is unsure about the mentorship due to feeling overwhelmed, intimidated, etc. may seem uncommitted and unresponsive. | Outside of set meeting times, text messaging and emails can be useful tools for communication. In written correspondence, avoid long-winded text with little in the form of an answerable question. Rather, frame questions so that they can be answered with a yes or no, reserving longer concerns for face-to-face meetings. |

While it can seem that mentorships need to be either in-person connections or digitally developed, the best option is a mix of both. A mentor and mentee who can leverage digital tools in their relationship can stay connected better. In addition, having occasional face-to-face meetings can deepen the connection between the participants.

Project-Based Mentoring

As determined through IRI’s assessment of mentorship best practices, one of the most effective ways to ensure engagement between mentors and mentees is project-based mentorships. Project-based mentorships consist of mentors working through a standalone project in collaboration with their mentees, allowing them to learn through shared experiences, often through a small grant awarded to one or both organizations. Despite the incentive for increased engagement, before engaging in this type of mentorship activity, mentors and mentees should review the pros and cons of this type of mentorship.

Pros

- Application of knowledge gained through the mentorship; learn by doing.

- Opportunity for the mentee to work closely with and ask questions of the mentor throughout the entire program lifecycle.

- Increased incentive for mentor if project funding is offered.

- Possibility for the mentee to be embedded within and benefit from mentor network in the long run.

Cons

- Substantial time commitment.

- Difficult to adjust if mentor/mentee relationship is not productive.

- Often requires additional funding.

- Difficult to coordinate if mentors and mentees work in different regions or sectors or have different approaches to their work.

Reviewing the Mentorship

Over time, the nature of the mentoring relationship may vary and support needs could change. Therefore, it is important that mentors and mentees constantly reevaluate mentorship goals, monitor progress made toward achieving them, and explore aspects of the mentorship that may have helped or hindered progress.

Reviewing the Learning Agreement

It is important to periodically review the mentorship Learning Agreement to determine whether expectations are being met. If not, the exercise of reviewing the agreement can be an initial step of getting a mentorship back on track. In instances where expectations shift, it may be beneficial to adjust the Learning Agreement. In these cases, it is important that the mentor and mentee discuss the shifts together and sign the updated agreement.

Reviewing the Mentorship Plan

In each mentorship meeting, time should be set aside to talk about progress made toward meeting the concrete goals defined in the mentorship plan. Based on this conversation, mentors should use check-ins with their mentee to ensure the plan is still relevant, as well as to assist the mentee in revising or adding to the plan, if necessary. The following is a step-by-step outline for a mentee-led conversation focused on reviewing the mentorship plan.

| The Mentee… | The Mentor Then… | |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Describes in detail actions successfully taken to reach their mentorship goal. | Positively reinforces mentee success and, if needed, provides constructive feedback. |

| Step 2 | Outlines in detail challenges faced in trying to reach their mentorship goal. | Asks how they overcame challenges or, if necessary, facilitates a brainstorming session to help identify feasible solutions. |

| Step 3 | Sets action steps to meet goals to complete before the next meeting. | Provides feedback on best practices related to outlined action steps and discusses resources available. |

| Step 4 | Provides constructive feedback to the mentor on how they can best help moving forward. | Humbly takes feedback into consideration and discusses how they will actualize feedback leading up to the next meeting. |

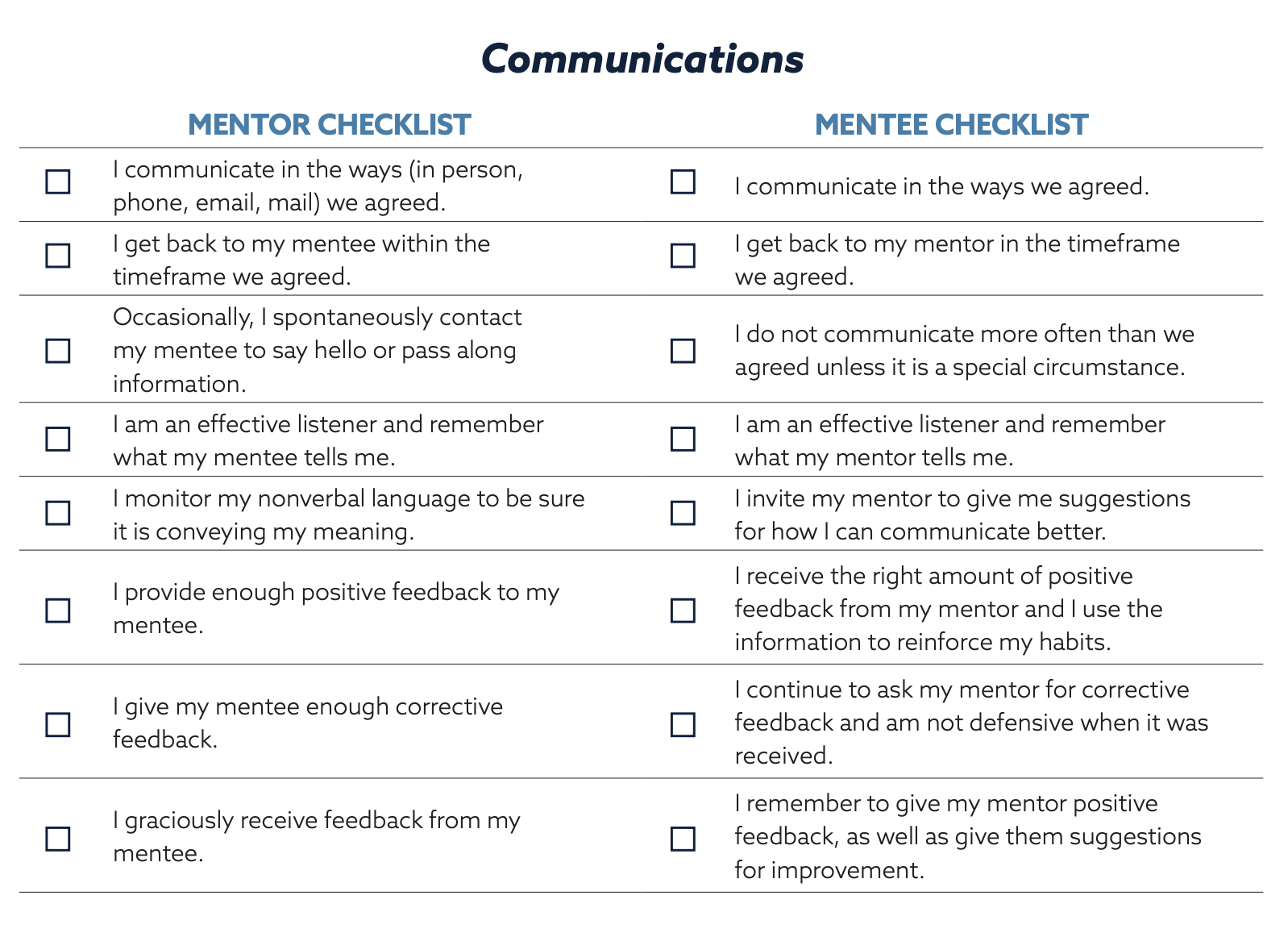

Reviewing the Mentor-Mentee Relationship

There are numerous other aspects of a mentorship that should be reviewed to determine if changes in the relationship need to be made. In particular, it is essential to review the levels of communication and trust in the mentorship relationship, which can be done using the checklist below. If criteria are not being met, mentors and mentees should have a conversation about ways they can improve their level of trust and communication, with the aim of having all criteria met by the end of a formal mentorship program.

Mentorship Adaptions

Mentoring Vulnerable Groups

When mentees belong to a vulnerable group, a mentor should be prepared to face different challenges that may affect the successful implementation of their mentorship.3 These contextual challenges and obstacles can be structural and social. Structural challenges can be related to digital connectivity and (lack of) access to transportation. For example, access to an internet connection, electricity or roads can affect the communication between the mentor and the mentee as well as the success of the action plan. These impediments often disproportionately affect people who belong to vulnerable populations. Social challenges are also more common when working with vulnerable groups. Prejudices and cultural stigmas can often translate into discrimination, invisibility or unequal treatment that may affect a mentorship’s success.

Mentor Preparation

These diverse realities of mentees from vulnerable populations require the mentor to conduct a primary assessment of the different obstacles and opportunities influencing the success of the mentorship. Through an assessment, mentors will have a better understanding about what capacities will most effectively help the mentee to achieve their goals.

Research

One of the first steps in a mentor’s preparation should be to understand the ecosystem in which the mentee is operating. The structural and social barriers that are uncovered through primary and secondary research will inform how the mentor and mentee set mentorship expectations and goals. The mentor should keep in mind that, even with background research, mentees in each group can face specific challenges associated with membership in vulnerable groups.

| Primary Research | Secondary Research | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Any type of research that someone collects themselves. | Any type of research that uses already existing data. |

| Source(s) | Interviews; observation. | Official documentation; news and other media; reports from international cooperation organizations or other civil society organizations. |

| Topics to Research | Culture, including traditions and taboos; types of discrimination affecting a vulnerable group; important power-brokers in the community. | Political background, including government leaders and structure (one-party communist state, multiparty democracy, etc.); history; specific language codes; legal frameworks that affect a vulnerable group. |

| Example of Benefit | In the case of primarily Afro-descendant CSOs in Panama, by the mentor meeting with different leaders identified in the community, they were able to have a better understanding of the mentee’s operating environment and associated and different challenges of the community. | IRI Panama gave a training to Emberá-Wunaan women in the eastern province of Darien in 2016. For IRI to be able to implement the training, it was necessary to first reach out to the community chief of that indigenous group and get his approval. By doing desk research of local laws, IRI was able to ensure the program started out on the right track. |

Things to Consider

A one-size-fits-all approach cannot be used to ensure successful mentorships with all vulnerable groups. Rather, it is important to understand the unique challenges and varying best practices for engaging mentees from different populations. The chart below outlines things to consider when designing a mentorship for these groups. A mentee can also face challenges stemming from membership in multiple vulnerable groups, which should factor into the development of the mentor plan. While far from exhaustive, the following list enumerates some of the fundamental factors to consider when beginning a mentoring relationship with a mentee from a vulnerable population.

Women

- Gendered discrimination, harassment and violence.

- Lowered expectations of women and their capabilities.

- Fewer opportunities provided to women, including skills-building and leadership opportunities.

- Lack of or limited access to technology and internet compared to men.

- Gender roles and norms can potentially undermine women’s active participation (as compared to men) in a mentorship program.

- Gender dynamics, especially between men and women, may lead women to feel like they are unable to speak as freely with a male mentor.

- Other factors that may lead to a confidence gap between women and men.

Youth

- If the mentee is a minor (under 18 years of age), the mentor should obtain written authorization from a parent or guardian for the mentee to participate in the process.

- Many young people have limited access to financial resources for non-essential activities. It is important to design a mentorship based on the economic capacities of the young people and contemplate if it is possible to budget funds for food, communication tools and transportation that may be associated with mentoring activities.

- When working with young people living in a context of social risk (poverty or insecurity), it is important to consider that they may have reserved or defensive attitudes that limit the communication processes in mentoring. It is important to be flexible and sensitive when asking questions about the mentee’s environment, family circle or friends, in order not to cause discomfort.

- Youth mentees may find it difficult to trust and openly communicate with mentors, who are typically much older. In addition to the diligent practice of trust-building behaviors and activities, mentors may find it helpful to invite someone in both the mentor and mentee’s network of friends or peers to facilitate the first mentorship meeting. In other words, “to break the ice.”

Ethnic and Linguistic Minorities and Indigenous Groups

- When deciding if a mentorship pairing can be successful, it is important to consider if the mentor and mentee share a common language. Even if the mentor is a great fit in every other way, having to communicate through a translator will hinder open and efficient communication between the mentor and mentee.

- Materials used during the mentorship should be in the mentee’s first language. It can also be helpful to look for resources that include infographics and pictures that visually depict information.

- In many countries where IRI has worked, indigenous groups have a high level of political autonomy. As such, it is important to take care not to violate their internal regulations. Sometimes having the authorization or the support of the central or regional government is not enough to be able to work in an indigenous area — it is important to approach the local leaders.

Religious Minorities

- The mentor should have an in-depth understanding of the mentee’s religious traditions that may impact how they develop a relationship with a mentee. For example, some religions may not allow a female mentee to be mentored by a man in a private setting. Additionally, it is important for mentors to foster trust with mentees by respecting their mentee’s cultural traditions.

LGBTIQ+

- Mentors should familiarize themselves with definitions related to sexual orientation and gender identity. For example, mentors should respect and use the terms, names and pronouns that mentee uses to refer to themselves. This is a key way to ensure trust is built between the mentorship partners.

- Depending on the local political context, LGBTIQ+ people may face different forms of discrimination, ranging from social marginalization, to the risk of physical violence and hate crimes, to laws enacted to punish homosexual acts or gender nonconformity. Mentors should assess the local context when determining how to approach mentorship expectations and goal setting to ensure the mental and physical safety of their mentees.

- Generate a safe and open environment by proactively committing to diversity, inclusion, dignity and respect. Mentors should explain to their mentee that they do not discriminate based on gender identity, sexual orientation or any other characteristic.

People with Disabilities

- Mentors should enter the mentoring relationship with the mindset that the barriers faced by mentees are societal and structural, rather than residing in the person.

- When working with people with disabilities, the mentor must select places or physical spaces based on the universal or inclusive design model. When this is not possible, mentors must make use of reasonable accommodations that allow the inclusion and participation of people with disabilities. This may include interpretation of sign language, electronic equipment and Braille writing to enhance communication and/or inclusion of people with disabilities.

Working in Restrictive Spaces

When working in restrictive spaces, there are additional challenges that may impact a mentorship’s success. These include:

- Location: Mentorships in closed spaces are often oriented toward a leader in a mature, open civil society providing guidance to a mentee in a developing, often clandestine operating space. As such, the mentor is typically not based in the same country as the mentee. At the onset of the mentorship, a communication plan should be developed that outlines secure methods of communication and topics that are off limits.

- Security: When mentee organizations work on democracy or human rights, this represents a threat to authoritarian regimes. When mentor organizations are based in a different country, some shared experiences or activities that seem normal for an open society could be dangerous to execute by the mentee in a restricted space. The mentor must work closely with the mentee to analyze which activities can reach the goal without putting the security of the mentee at risk. This will require extra creativity and a deep understanding of the context in which the mentee is operating.

- Communication: When executing a mentorship in a restrictive space, always assume that there is no privacy in communications. Although several secure communications services are available (like Telegram or Signal), no one method is perfect, and any information can be monitored by authorities that could put the mentee in danger. The mentor and mentee should assess the risks associated with their electronic and in-person communications to determine appropriate methods.

- Connectivity: In restrictive spaces, governments try to limit citizen connectivity. Mentors should be prepared to be patient and creative in finding the best times and methods to connect with their mentee. This also relates to the mentor and mentee making the most of every meeting to reduce the number of connections that would lead to complications in the process. In these circumstances, mentees should pay extra attention to developing an efficient and effective agenda for each mentorship meeting.

It is advisable to contemplate technological tools to improve communication and connectivity when planning to start a mentorship in a restrictive space. It is preferable that these tools do not demand a significant amount of mobile data or require specialized, expensive equipment. In IRI’s experience in restrictive spaces, the use of WhatsApp, Telegram and Signal has been particularly useful as a discussion forum and to share materials from trainings using voice memos.

Attachment A: Setting Expectations

Use this worksheet to develop an understanding of what you expect to gain from your mentoring relationships. By clarifying your own expectations, you will be able to communicate them more effectively.

The mentee should take the lead in this exercise and go through the following list, checking off what they expect from their mentor and the mentor-mentee relationship.

While the mentee is going through the list, the mentor should feel free to ask questions to clarify mentee expectations in order to set mutually agreed-upon ground rules.

I hope that my mentor and I will independently:

- Receive encouragement and support

- Increase my confidence when dealing with different stakeholders Challenge myself to achieve new goals and explore alternatives

- Gain a realistic perspective of the field

- Get advice on how to balance work and other responsibilities, and set priorities

- Gain knowledge of “dos and don’ts”

- Learn how to operate in a network of talented peers

- Other _______________________________________________________________

I hope that my mentor and I will:

- Tour my mentor’s workplace

- Meet over coffee, lunch or dinner

- Go to educational events such as lectures, conferences or other events together

- Go to local, regional and national professional meetings together

- Other _______________________________________________________________

I hope that my mentor and I will discuss:

- Professional-development subjects that will benefit my organization

- Funding options and search preparation

- The realities of the situation for social organizations

- My mentor’s work

- Technical and related field issues

- How to network

- How to balance work and family life

- Personal goals and life circumstances

- Other ______________________________________________________________

The things I feel are off limits in my mentoring relationship include:

- Disclosing our conversations to others

- Using non-public places for meetings

- Sharing intimate aspects of our lives

- Meeting behind closed doors

- Other _______________________________________________________________

I hope that my mentor will help me with opportunities by:

- Opening doors for me to funding possibilities

- Introducing me to people/foundations/institutes etc. who might be interested in supporting my organization

- Helping me practice outreach techniques

- Suggesting potential contacts for me to pursue on my own

- Teaching me about networking

- Critiquing my organization’s background documents

- Sharing professional development opportunities

- Other _______________________________________________________________

Anything else to add? Please use the space below to note additional agreed-upon expectations.

Attachment B: Mentorship Learning Agreement

Mentors and mentees: please complete this Learning Agreement together. Use the template below to delineate your expected project outputs, mentorship expectations and timeline. This document was developed using IRI partner Learning for Development Association’s Learning Agreement template.

Attachment C: Mentorship Plan

Footnotes

- Just because goals are set, that does not mean that these goals cannot change. This will be discussed later in the guide.

- IRI has found that the acquisition of funding is often a key priority at the expense of focusing on other, sometimes potentially more beneficial, areas of growth. Mentors should try to balance these priorities by highlighting opportunities and tradeoffs, such as focusing on building government relationships, strategic communications plans, implementing low-cost grassroots programming, etc.

- Vulnerable groups include, but are not limited to, the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and questioning (LGBTIQ+) community, women, youth, indigenous communities and people with disabilities.