The Challenges Facing Plainland Ethnic Groups in Bangladesh: Land, Dignity, and Inclusion

Overview

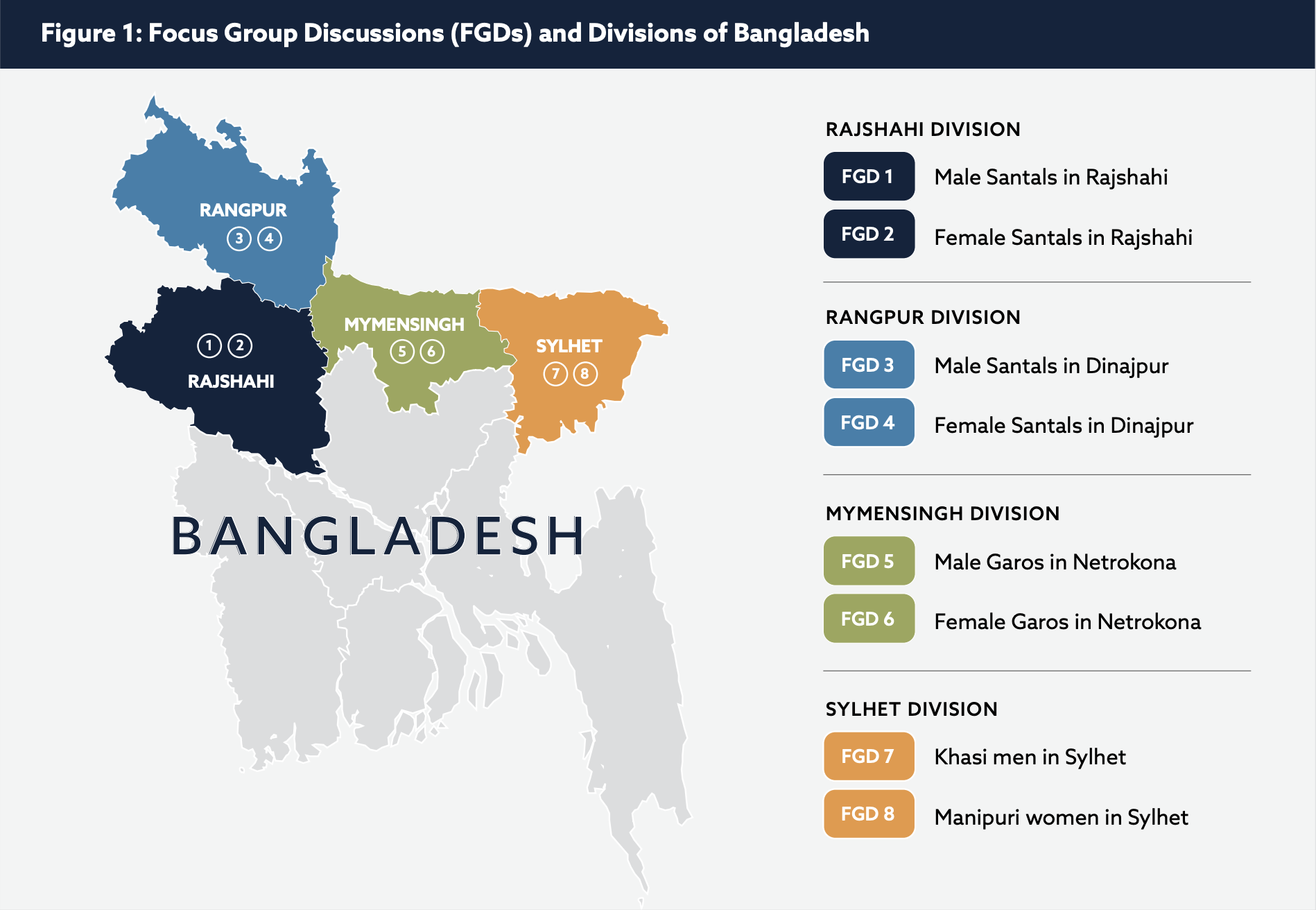

In February 2020, the International Republican Institute (IRI) conducted a focus group study of plainland ethnic groups in Bangladesh, which are religiously and linguistically distinct, non-Bengali communities that live primarily in the northern divisions of Bangladesh: Rajshahi, Rangpur, Mymensingh and Sylhet. The study examined the challenges and needs of the following four groups: Santals, Garos, Khasis and Manipuris.1

IRI partnered with a local research firm to conduct eight focus group discussions (FGDs) across four districts:

Men and women were separated into different FGDs. Each FGD was composed of between 10 and 13 participants and included different age groups and professions. In total, 85 individuals participated in the study (41 men and 44 women).2 As is common with qualitative research, the statements in these FGDs do not necessarily represent the general opinion of the ethnic minorities included in the study.

Background of Plainland Ethnic Groups

There are approximately two million people from 27 officially recognized ethnic minority groups in Bangladesh.3 They constitute approximately 1.25 percent of Bangladesh’s population. There are two broad categories of ethnic minorities in Bangladesh: groups that reside in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) in the southeastern Chattogram Division,4 and groups that reside in the northern divisions, often referred to as plainland ethnic groups.

In 1977, the ethnic minorities in the CHT launched a violent insurgency against the state to preserve their land and autonomy. The insurgency ended with a peace accord in 1997 that recognized the “special status” of the CHT ethnic minorities. In contrast, the less restive ethnic minorities of northern Bangladesh have received less attention.

These plainland ethnic groups are historically, socially and politically marginalized; reside in isolated and largely impoverished areas; and receive little attention from local or national politicians.

Bangladesh’s ethnic minorities have histories, identities and traditions that are distinct from mainstream Bengali society. Although some ethnic minorities are Muslim or Hindu, many are Christian, Buddhist, animist or hold a mixture of religious beliefs. They speak their own languages and often have unique cultural practices, including dance, food, drink, clothing and social structure (several are matrilineal). Since many of these ethnic minorities emigrated from China, Burma and India,5 their facial features and skin color are often different from Bengalis, making them easily identifiable.

Key Findings

Finding 1: The key concern of plainland ethnic communities is the preservation of their land.

During the British (1858-1947) and Pakistani (1947-1971) periods of rule over the territory that is now Bangladesh, government officials and local people manipulated plainland ethnic groups out of their land. Many ethnic communities paid land taxes but did not have a tradition of keeping records. Later, when the government put ethnic peoples’ lands up for auction, they had no way to claim their rights. A Santal man from Rajshahi said, “In the British period we owned a lot of land. Our ancestors were deceived because of lack of education.”6 In these early periods, ethnic minorities did not speak Bangla fluently or understand legal terms. Another Santal man from Rajshahi recalled that Santals did not know the English word “acre” and the Bangla word for 12 (baro) is the word for one in their ethnic language. These linguistic confusions were known among Bengalis and were used to create legal contracts that disadvantaged Santals.

As the educational and linguistic capacity of ethnic minorities grew, this type of overt manipulation became less common. However, the consequences of large-scale land dispossession remain a key issue. A Santal man from Rajshahi said, “We were fooled and cheated out of our own lands. These days we don’t have the proper ownership of our lands. I can’t sell my land because my papers and documents aren’t ready.” Santal men and women in Rajshahi and Dinajpur said Bengalis have forcibly taken land that hosts or is near Santal graveyards and temples; without land deeds, Santals have little recourse.

We were fooled and cheated out of our own lands. These days we don’t have the proper ownership of our lands. I can’t sell my land because my papers and documents aren’t ready.

SANTAL MAN FROM RAJSHAHI

The courts have provided little justice for ethnic minorities. Several Khasi participants said that in Sylhet they have unsuccessfully petitioned the court to reclaim profitable tea garden land that was taken by the government after Bangladesh’s independence in 1971. A Manipuri woman in Sylhet explained that Bengalis will enter into agreements with ethnic minorities to buy or sell land and then violate the terms of the agreement, but the courts will not intervene.

Across all FGDs, participants said preserving their land was a key challenge, including lack of legal documentation to fight off claims to ethnic lands, illegal encroachment on ethnic areas and unresponsive courts.

Finding 2: Despite growing acceptance, plainland ethnic groups continue to face social ostracism and discrimination from mainstream Bengali society.

While most participants said that the treatment of ethnic minorities has improved in Bangladesh, they also cited various forms of continuing discrimination. In some areas, Bengalis refuse to eat or interact with ethnic people. A Santal woman from Rajshahi said, “When you go to any hotel, if you are a Muslim you will be given one cup, and I will be given a different type of cup.” A Santal man from Dinajpur similarly noted that when eating at a restaurant, he and a friend were given plastic glasses instead of the normal glasses given to Muslim patrons. “When we go to picnics,” explained a Santal woman from Rajshahi, “schoolchildren are told to bring their own plates.”

Ethnic minorities also face mockery. Santals are ridiculed for their dark skin; Garos for their Asian facial features. A Manipuri woman from Sylhet said people in her community are mocked for their poor Bangla pronunciation. Another Manipuri woman from Sylhet said, “We have to face many things in the battle of life. It seems to me that we are underestimated.” A Santal man from Dinajpur explained, “[Bengalis’] mentality depends on our religion …. When God sent me to this Earth, did he tell me, ‘Rathin,7 you are a Santal, so I have created you differently?’” He continued, asking of those who discriminate based on religion and ethnicity, “What’s the problem? Is it with my face or your heart?”

Garos, who have Asian facial features and commonly hold jobs in the service sector in large urban areas, are easily identifiable. In the FGDs, Garo participants said they face various indignities, including being ridiculed for their appearance or ethnic clothes, or being removed from seats on public transportation. A Garo woman from Mymensingh said teachers insult Garo students. “They think that we don’t have any brains,” she said. A Garo man said, “Many Bengalis say that we are not Bangladeshi. We are outsiders.”

Many Bengalis say that we are not Bangladeshi. We are outsiders.

Garo Man

Despite such discrimination, participants said they felt pride in their ethnic identities. A Santal woman from Dinajpur said, “I feel proud to identify myself as a Santal. Not everyone gets the opportunity to express their true identity. So, I feel proud to do this. And we all are Bangladeshis in Bangladesh.” A Garo female participant from Mymensingh, who holds a reserved seat for women on a local council, said defiantly, “As we are public representatives, we get [Bengalis’] salaam.8 But in reality, we don’t care whether they value us or not.”

Finding 3: Many plainland ethnic groups face difficult living conditions, including poor housing, unsafe drinking water and insecurity.

For both cultural and practical reasons, many participants described their ethnic communities as self-sufficient. These distinct cultural groups have long lived in isolated areas, which has forced them to rely on other community members instead of government support or other forms of outside assistance. Consequently, ethnic people often face difficult living conditions. Some of these difficulties are not unique to ethnic minorities in Bangladesh, but they are often exacerbated by discrimination.

Housing in ethnic communities is often rudimentary. Most houses are made of mud, tin or thatched material. “Our housing condition is miserable,” said a Santal man from Dinajpur. Many Manipuri and Khasi respondents from Sylhet said their mud houses are a problem during the rainy season. In contrast to other participants, most Garos said their housing is adequate.

Some ethnic communities lack consistent access to safe drinking water. Santal participants generally said drinking water in their areas is safe. Government agencies and NGOs periodically check their water quality. However, Garo participants, who live in Mymensingh and Sylhet, and Khasi participants, who live in Sylhet, said their water is contaminated with iron and arsenic, and not tested often. Consequently, people in these areas often suffer from waterborne diseases like typhoid. The problem is particularly acute in Khasi communities — one participant said unsafe drinking water is the main problem in their community.

Poverty in these communities also contributes to other social problems. A Santal woman from Rajshahi said, “We Santals face poverty as the main problem. Because of that, we can’t get a good education.Those who are slightly more educated have a job; they can educate their children even if it is only slightly more than themselves. But the others can’t.” Lack of income also creates an incentive for marrying off daughters at a young age. Another Santal woman from Rajshahi said child marriage is a key problem in her area.9 “I have seen that if a girl is in class eight or nine [generally age 14 or 15], she has to be married off.”

We Santals face poverty as the main problem. Because of that, we can’t get a good education.Those who are slightly more educated have a job; they can educate their children even if it is only slightly more than themselves. But the others can’t.

Santal WOMAN FROM RAJSHAHI

Insecurity is not a widespread problem among ethnic communities, but many participants complained that Bengalis generally face no punishment if they harass or attack ethnic people. A Santal man from Rajshahi said, “[Bengalis] say, ‘They are Santals, nothing will happen if we beat them up.’” Another Santal man from the same area said, “[Bengalis] think that we won’t be heard, and the police won’t take us seriously.” A Khasi man from Sylhet contended, “Police don’t care about us.” A Garo man from Mymensingh alleged the police are helping Bengalis illegally settle on his family’s land.

Ethnic women complained of feeling insecure when outside their communities. Several Santal women complained that Bengalis will tease or harass ethnic women on the streets. A Santal woman from Rajshahi explained, “A Muslim boy can hold the hand of a Santal girl …. I have seen that our girls can’t protest. They are not strong. If a Santal boy holds the hand of a Muslim girl, 10 people will come to investigate the matter.” A young Garo woman from Mymensingh said, “As we are young, many young boys try to talk to us.

Finding 4: Government services and benefits are poor or absent in some areas with large ethnic minority populations.

Although government services are generally weak in Bangladesh, ethnic minorities face two key exacerbating factors for accessing services: the remote location of many ethnic communities and discrimination.

All ethnic communities have access to the government health care system, which includes divisional hospitals, a health center in each local administrative area (upazila) and community clinics. However, participants complained about the lack of hygiene and poor services at these health facilities. Community clinics generally do not have adequate medicine and certified doctors rarely visit. A Garo woman from Mymensingh said, “I want to say something about governmental medical facilities for indigenous people. Though there is a community clinic, the health workers don’t visit regularly. I don’t think they have any medicine except Paracetamol tablets and oral saline. That’s why we’ve stopped going there totally.” Other participants said the health centers in their areas were often closed and the divisional hospitals too far to visit.

Others alleged discrimination in the provision of health services based on ethnicity and class. A Santal woman from Dinajpur alleged, “I was infected with dengue fever. I felt like I was going to die. I couldn’t breathe. It was so serious. I went to [the] doctor and asked for a bed. He refused. He told me that a bed wasn’t available.” A Khasi man from Sylhet said nepotism contributes to denial of care. “Nepotism means we have no doctor or higher-educated government job holder from our tribe. So, when we go there, they ask us questions like who we are, where we’ve come from.”

In June 2019, the Government of Bangladesh eliminated all job quotas, which had ensured government jobs for ethnic minorities and other groups.10 However, even when the quota was in place it was often negated by bribes. A Santal man in Rajshahi said, “Suppose, in our union, the primary school or high school is recruiting teachers for two vacant posts, and five people passed the exam. If they come to know that one of them is Santal, they will ask for a larger bribe than from the other applicants.” Ethnic people also recounted instances of prejudice in the workplace. A Khasi man from Sylhet stated, “When I entered into work life, I faced some weird experiences. Others treat us as if we don’t understand anything and don’t know how to work. They acted like we were not educated.”

When I entered into work life, I faced some weird experiences. Others treat us as if we don’t understand anything and don’t know how to work. They acted like we were not educated.

Khasi Man from SYLHET

In Bangladesh, the government provides a set of guaranteed allowances for traditionally vulnerable groups including the elderly, mothers and widows. Yet these allowances are often out of reach for ethnic people because of excessive bribes, remote government offices or discrimination.

A Santal woman from Rajshahi said mothers in her area cannot travel the long distance to the local government office for the motherhood allowance. A Santal man from Dinajpur complained that his area does not receive the elderly allowance. He said: “Muslims are the majority in our area. And Santals only have 75 families. Each family has at least one elderly member. Don’t they have the rights?” A Garo woman from Mymensingh claimed, “In some cases, such as the old age allowance, widow’s allowance and others, they don’t give us priority because we’re aborigines. Even those who are 90 years old don’t get their pensions.”

The denial of government benefits to ethnic minorities is often linked to contested land.

Santal and Khasi participants said that because their ownership of the land is disputed, many ethnic families do not have a valid legal address — making it difficult to receive benefits or apply for government jobs.

Bangladesh has a large nongovernmental sector that often provides services in areas where state capacity is low, but NGOs have generally failed to fill the gap left by poor governance in ethnic villages. “Many NGOs talk about working for us and say that we will be given priority, but they do not do so,” said a Santal man from Dinajpur.

Finding 5: Plainland ethnic communities feel unrepresented and ignored by the political system.

Many participants said politicians, political parties and local government officials do not provide enough support to ethnic communities. Most participants said politicians visit while campaigning for election but disappear afterward. A Garo woman from Mymensingh said, “Just before the vote, the politicians visit several houses. But after getting elected, they forget all their promises.” A Santal woman from Dinajpur complained, “There should be some political figures who are concerned about us, but we don’t have any such figure in our community. We need one.”

After elections, ethnic people have difficulty getting the local government’s attention. A Garo woman from Mymensingh said, “We don’t even get solutions to small issues in the subdistrict. Our sandals tear off because of going [to the government office] again and again.”

Because plainland ethnic groups often vote for the ruling Awami League (AL), many participants argued that AL politicians now take the ethnic vote for granted, while Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) politicians think they have no support in these areas. “So, both parties have no concern for us,” said a Khasi man from Sylhet. A Santal woman from Rajshahi said local BNP supporters have threatened revenge on the community because of its support for the AL. “BNP people still threaten us this way: ‘If the BNP ever comes to power …,’” she said.

We don’t even get solutions to small issues in the subdistrict. Our sandals tear off because of going [to the government office] again and again.

Garo Woman from MYMENSINGH

Beyond voting, ethnic people generally do not actively participate in politics and have few representatives at the local or national level. Participants said lack of money, religious discrimination and small populations limit the ability of community members to win elections. A Garo man from Mymensingh said that Garos who hold political positions still do not wield much power because of their identity. In the current National Parliament, there is one Member of Parliament (MP) from plainland ethnic communities, who is a Garo from Mymensingh Division.11

Conclusion

Plainland ethnic groups live in remote areas of Bangladesh and are politically marginalized. These groups face prejudice, difficult living conditions, failing government services and land dispossession built on historical discrimination. With limited representation at the local and national level, plainland ethnic groups have few voices to advocate on their behalf. International and domestic NGOs should continue to press for the rights of the plainland ethnic community and assist Bangladesh’s ethnic minorities in finding ways to advocate for themselves.

Footnotes

- Basic historical and demographic information on each group: Santal (Population: 200,000; Area: Rajshahi Division, Rangpur Division; Emigrated from: India; Religion: Hindu and Christian); Garo (Population: 150,000; Area: Mymensingh and Sylhet; Emigrated from: China; Religion: Mostly Christian); Manipuri (Population: 25,000; Area: Sylhet; Emigrated from: India; Religion: Hindu sect); Khasi (Population: 30,000; Area: Sylhet; Emigrated from: India/ Tibet; Religion: Mostly Christian).

- The FGDs were conducted in Bangla. Though most Bangladeshi ethnic groups speak their own unique language, nearly all ethnic people also speak Bangla.

- The exact size of Bangladesh’s ethnic population is unknown because of complications in identifying and counting ethnic groups in the census. The INGO Minority Rights Group International provides partial data on ethnic groups at https://minorityrights.org/country/bangladesh/.

- Formerly called Chittagong Division

- Bangladesh’s ethnic groups are not new to the area. Some immigrated to the land now known as Bangladesh during the Mughal Empire (1526 to 1857) or British rule (1858 to 1947) in the subcontinent, while others trace their roots in the area to hundreds of years before these periods.

- The FGDs were conducted in Bangla. Therefore, quotes cited in this report were translated from Bangla to English and have been minimally edited to ensure clarity. As much as possible, the English translations preserve the syntax, word choice, and grammar of the Bangla speaker.

- The participant’s name has been changed to retain his anonymity.

- To give salaam is to offer a verbal Islamic greeting to another person. It is interpreted as a sign of respect to the person who is being greeted.

- Child marriage is not unique to ethnic communities in Bangladesh. According to the United Nations, Bangladesh has the fourth-highest rate of child marriage in the world and the second-highest absolute number of child brides. As of 2017, 59 percent of girls in Bangladesh were married before their 18th birthday and 22 percent were married before the age of 15.

- The Government of Bangladesh eliminated all job quotas in response to a student-led protest movement against job quotas for the descendants of those who fought against Pakistan in Bangladesh’s Liberation War in 1971. The protests did not target ethnic quotas specifically, but these were eliminated along with other quotas in response to the protest movement.

- There are four MPs from the ethnic groups in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) in southeastern Bangladesh. The ethnic communities in these areas are distinct from the plainland ethnic groups in northern Bangladesh. Ethnic groups in the CHT constitute a majority of the local population, which makes it easier to elect representatives from their communities. Because of long-running conflict in the area, the ethnic groups in the CHT are more politically mobilized than other ethnic groups.