Bangladesh: Urdu-Speaking “Biharis” Seek Recognition, Respect and Rights

Overview

In early 2020, the International Republican Institute (IRI) conducted a qualitative research study of the Bihari community in Bangladesh — an Urdu-speaking linguistic minority group in the South Asian nation. The study examined the challenges and needs of Biharis in different locations around Bangladesh.

The term “Bihari” refers to approximately 300,000 non-Bengali, Urdu-speaking citizens of Bangladesh who came to what was then East Pakistan mostly from the Indian states of Bihar and West Bengal after the Partition of India in 1947. As Indian Muslims, Biharis joined Muslimmajority East Pakistan, but did not share the linguistic and ethnic background of the Bengali majority in the east, which spoke Bangla.

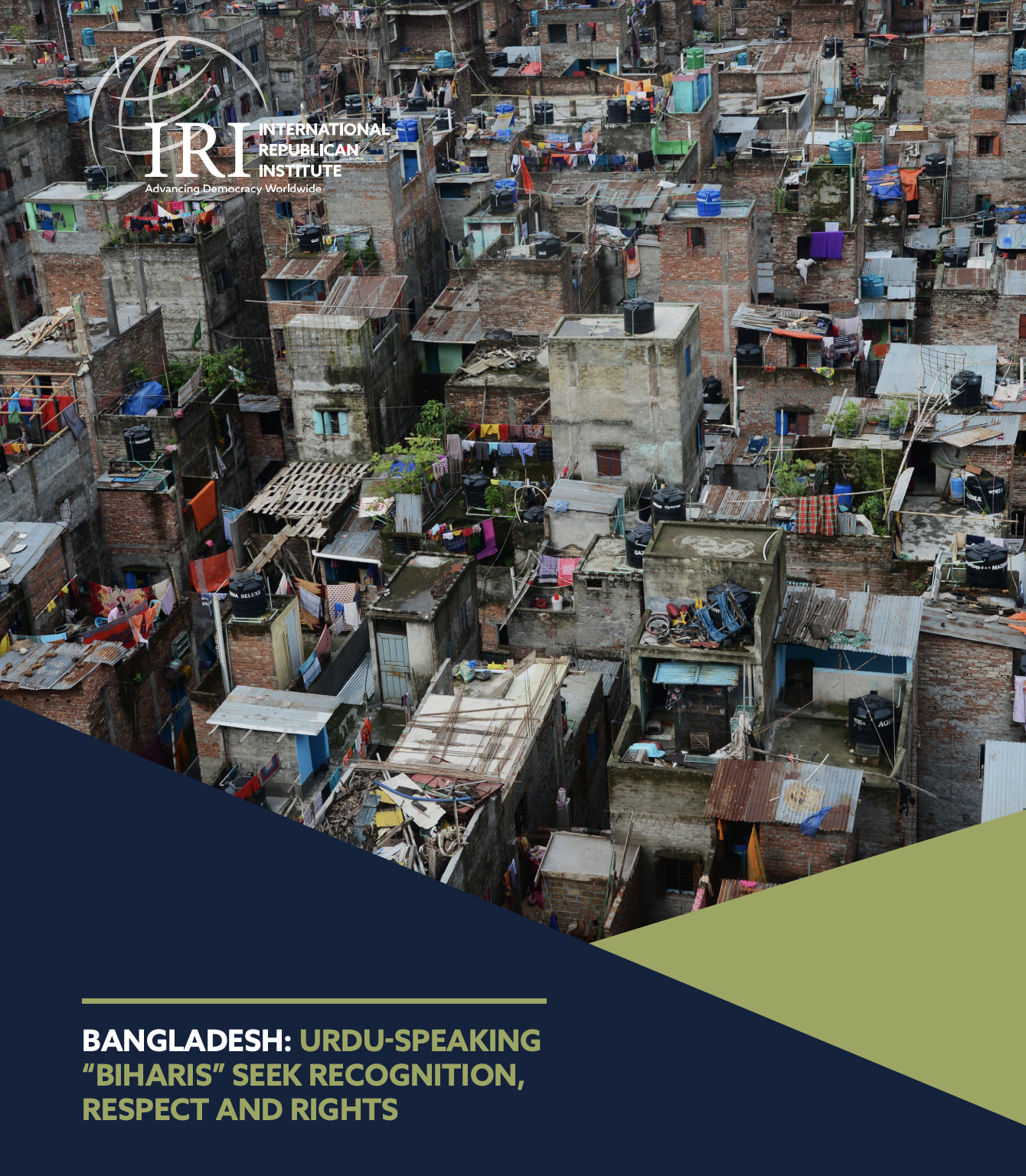

After years of discrimination from West Pakistan, East Pakistan declared independence as Bangladesh in 1971 triggering the Bangladesh Liberation War. Many Biharis supported or joined the Pakistani army’s failed attempt to maintain Pakistan’s territorial unity, which included significant atrocities against Bengali nationalists. After Bangladesh’s independence, many Bangladeshis viewed Biharis as traitors, but the Pakistani government agreed to accept only a small percentage of Biharis into Pakistan. The remaining Bihari community settled into 116 slum-like “camps” around Bangladesh, where they have remained since 1971.

Over the past five decades, the Government of Bangladesh has made some effort to improve the rights and welfare of Biharis. In 2008, Bangladesh’s Supreme Court recognized Biharis’ right to citizenship in Bangladesh and called for their inclusion on voter rolls. However, the living conditions in Bihari camps remain poor. The Government of Bangladesh has long promised to “rehabilitate” Biharis — to provide them housing outside the camps that is integrated into the Bangladeshi community. This has not occurred. Socially and politically, Biharis are also marginalized. Some Bangladeshis still view Biharis with suspicion and they are often considered anti-Awami League (the current ruling party), which led Bangladesh’s liberation movement.

Now several generations removed from the Liberation War, many Biharis are eager to join mainstream Bangladeshi society. To understand Biharis’ beliefs, challenges and needs, IRI partnered with a local research firm to organize eight focus group discussions (FGDs) spread across the major Bihari population centers: Chattogram (two FGDs), Dhaka (three FGDs: Mirpur, Adamjee and Mohammadpur), Khulna (one FGD) and Rangpur (two FGDs: Saidpur). Each FGD consisted of between nine and 12 participants of both genders and different age groups. In total, 82 individuals participated in the study (41 men and 41 women). The FGDs were conducted in January and February of 2020. As is common with qualitative research, the findings from these FGDs are not necessarily representative of all Biharis’ opinions.1

I was born in this country and I am a citizen. I love this country dearly. Maybe previous generations didn’t understand this, but we do. If we were in Bangladesh back then, then we too would have fought for this country in the war. We too respect those who sacrificed their lives for this country. We love the language martyrs as well …. As I was born in this country, I love this land. I have become a citizen, so I want my rights.

Male, 37, Chattogram

Key Findings

Finding 1: Biharis face numerous challenges in their daily lives.

While many older participants noted that their lives have incrementally improved over time, they cited a range of persistent challenges in Bihari camps. While there was some variation between camps, the most common issues were raised across FGDs by both men and women of all ages.

In their daily lives, Biharis face social alienation, including mockery, harassment and discrimination because of their ancestry. As a result, many Biharis try to hide their identity by speaking only Bangla in public, but their national identification cards list their camp address. While marriage between Bengalis and Biharis is increasingly common, many Bengalis refuse to marry their children to Biharis. Employers often decline to hire Biharis, particularly for government jobs, or demand larger bribes for positions than is typical.2 A difficult job market often forces Bihari parents to take their children out of school so they can earn an income. Public and private institutions are often inaccessible or discriminatory.

Public and private universities often refuse admission to Biharis.

Some camp residents have access to adequate healthcare, whereas in other areas governmentrun hospitals are far away and private clinics are too expensive. State ministries often refuse to provide passports to Biharis in violation of Bangladeshi law or demand large bribes. While some participants said the police provide protection in the camps, others said police officers ignore their problems or unfairly blame Biharis for crimes.

The living conditions in the camps are poor. Housing is cramped and dilapidated. Whole families, often with six or more members, live together in a single room, with little space to sleep, study or cook. Fire is a constant hazard. Toilets are scarce and often dirty or broken. Participants reported that in many camps fewer than 10 public toilets service hundreds of residents. In some areas, drinking water is unclean. There are few playgrounds or green spaces. Camp roads are narrow, crumbling and flood easily.

Amid these daily challenges and indignities, participants said drug abuse and drug trafficking are rising in Bihari camps.

We were born in Bangladesh. In schools and colleges, people don’t like us. Why? We are humans before Biharis. I’m a Bangladeshi just like you.

Male, 18, MOHAMMADPUR

We share beds with two or three other people at night and then use the floor also.

Female, 22, ADAMJEE

If employers see a camp address, they put our applications under the others.

Male, 23, SAIDPUR

When people come to the secondary school level, they can’t continue their study. Who will support them? Our income sources are limited. Every house has at least five or six children. It’s not possible for parents to educate them all.

Female, 23, Chattogram

The condition of the toilets is so bad that you wouldn’t want to use it if you looked inside …. We use the toilet with our eyes closed.

Male, 28, KHULNA

We have the right to get a passport, but [the government] doesn’t give it to us. They make us get it in an illegal way. They take 10,000 taka [$120] from us even if the actual cost is 5,000 taka [$60].

Female, 19, MIRPUR

When we open the water tap, it looks like blood is coming out. The water is so dirty.

Male, 37, MOHAMMADPUR

Bengalis look down upon the camp residents. Whenever a girl from the camp is ready for marriage, they say, “She lives in a camp, no one will marry her.

Female, 35, SAIDPUR

Finding 2: Biharis want the government to provide housing outside of the camps.

In Bangladesh, the term “rehabilitation” refers to a government effort to provide Biharis new subsidized housing. Most participants said their primary hardship is living in the camps, from which many of their other daily challenges originate. The camps are squalid, unsafe and signify Bihari inferiority to other Bangladeshis. “Rehabilitation is most important,” said a Chattogram man, 27. “The government should allot plots for everyone …. Everything will be improved if there is rehabilitation.” A Saidpur man, 38, said, “We desperately want to stay outside the camps. It’s like a hell for us and we want to escape from here.”

For most participants, the ideal form of rehabilitation would be permanent housing that is not far from the current camps, so they can retain their jobs and integrate into the Bengali community. A Mohammadpur woman, 26, explained, “If there is rehabilitation, we don’t want to be left out. We don’t want a separate place for Biharis. We want to merge with the Bengali community. We want to be resettled in a place where both Biharis and Bengalis live side by side.”

The government should allot plots for everyone …. Everything will be improved if there is rehabilitation.

Male, 37, Chattogram

Finding 3: Bihari participation in politics is limited in most locations, and many say that politicians rarely keep their promises to the community.

The participants expressed mixed levels of interest in and attitudes toward politics. While most said they were interested in politics, others said they had more pressing concerns. A Saidpur man, 27, said, “We cannot think of politics. We are so worried about our earnings. If we get involved with politics, then we will starve.”

Participants said Biharis infrequently participate in formal politics, but some serve on elected ward councils — Bangladesh’s lowest level of government — or as organizers for a political party. Biharis sometimes face discrimination in politics because of their identity. A Khulna man, 50, described his experience running for a ward council position. One of his opponents, who was the son of a freedom fighter,3 would say in his speeches, “Is this why we liberated our country? To elect a Bihari?” The man concluded, “I could not get elected in that election being a Bihari.”

According to participants, Biharis’ political affiliation is mixed despite the community’s reputation as being sympathetic to the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). A Saidpur man, 25, said, “Everybody has their own choices. For example, I support Awami League. Some of us support BNP, and some others support Jatiya Party.” A Khulna man, 35, expressed a similar sentiment. “Despite the fact that there are Bihari people who support various ideologies … it is often said that Biharis do not vote for the Awami League. Whereas I myself voted for Awami League as did many of us who work in different factories,” he said.

One Khulna man, 24, reported facing discrimination at the polls. He alleged that when he went to his polling station during a city election in 2018, the polling agent — realizing he was from a Bihari camp — told him he couldn’t vote because he was a BNP supporter. “Your vote has been cast,” the polling agent said, “you can go now.” During election periods, participants claimed Biharis are harassed for their vote and their businesses are extorted for cash to fund campaigns.

Many participants felt manipulated and ignored by elected leaders. A Chattogram man, 37, said, “Even if we try ourselves, we cannot deliver our words to the upper levels.” Several participants in Saidpur said politicians often blame Biharis if they lose. A Saidpur man, 27, said, “Politicians try to manipulate us to get our votes. They use us and even blame us if the election results are not satisfactory.”

Participants said that while local politicians occasionally keep their promises to the community, national-level officials rarely follow through. A Chattogram woman, 26, explained, “[Politicians] only come to us during the time of voting.” A Mirpur man, 21, also complained about Bihari camp leaders. “The leaders in our camp are no better. They don’t talk about our rights. Their support can be bought.”

Politicians try to manipulate us to get our votes. They use us and even blame us if the election results are not satisfactory.

Male, 27, SAIDPUR

Most outside support in Bihari camps comes from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). A Saidpur woman, 38, said, “The little assistance we get is from the NGOs, not from the government.” Another Saidpur woman, 45, noted, “[Politicians] just make promises and do not keep them. Whatever we have gotten so far is mostly the contribution of NGOs.” Across Bihari camps, participants said NGOs have provided a range of assistance on housing, clean water, loans, food, education, sanitation and toilets. However, they feel that this aid has been insufficient to make substantial improvements in the camps.

Finding 4: Biharis identify primarily as “Bangladeshi.”

Most participants unequivocally identified as Bangladeshi. A Saidpur woman, 18, asked, “Why should we be called Bihari? We are not Bihari any longer. By birth we are Bengali and Bangladeshi.” A Mirpur man, 50, explained that Bengalis and Biharis share many commonalities. “Our language is Urdu and yours is Bangla. No other differences. Your Allah is my Allah too. We have the same prophet as well. We all eat the same food. There is no difference: some are rich and some poor; some are educated and some not …. We and our children are born in this country,” he said. A Mohammadpur woman, 27, said, “We love Bangladesh from the bottom of our hearts. Why can’t the Bangladeshis tolerate us?”

A Mohammadpur man, 37, remarked, “It was our forefathers who came from India to East Pakistan because of their Muslim identity. They may have a sense of anger, but why should we? This is the place where we [were] born.” A Chattogram man, 26, declared, “The patriotism we have is only for Bangladesh. We have never seen Pakistan …. Our love is only for Bangladesh. I don’t know why we are called Pakistanis, stranded Pakistanis, nonBengalis or Biharis.”

Our language is Urdu and yours is Bangla. No other differences. Your Allah is my Allah too. We have the same prophet as well. We all eat the same food. There is no difference: some are rich and some poor; some are educated and some not …. We and our children are born in this country.

Male, 50, MIRPUR

Conclusion

Nearly 50 years since Bangladesh’s independence, Biharis are now recognized as citizens but remain stranded in neglected encampments with few economic opportunities to improve their status. Many young Biharis have embraced Bangladesh as the only home they know and desire integration in Bangladeshi society. They seek jobs, education, safe living conditions and the same rights and protections that other Bangladeshi citizens are afforded. International and domestic NGOs should continue to support the Bihari community as they pursue social, political and economic advancement as full citizens of Bangladesh.

Footnotes

- Quotes cited in this report were translated from Bangla and have been minimally edited to ensure clarity. As much as possible, the English translations preserved the original syntax, word choice, and grammar. The FGDs were conducted in Bangla with a Bengali moderator. Nearly all Biharis in Bangladesh speak both Urdu and Bangla.

- Many Bangladeshis are forced to pay a bribe to get a job. Some participants said employers demand larger bribes from Biharis because of their identity.

- Those who fought in Bangladesh’s Liberation War against Pakistan in 1971 are often called “freedom fighters.”