Introduction

To inform the International Republican Institute’s (IRI) targeted effort to empower marginalized community voices, IRI conducted a barrier analysis to determine the barriers marginalized communities face to fully realizing their civil rights. IRI selected marginalized youth as a target group because youth are Laos’ largest marginalized community in terms of population and will therefore be a dominant force in the coming decades. Additionally, youth have proven to be a critical source of activity in many sensitive parts of the world, with younger generations possessing significant energy that can be harnessed for positive change. IRI specifically chose to look at intersectionally marginalized youth in Laos, as individuals who face intersecting layers of exclusion in their communities are particularly vulnerable to discrimination and disempowerment.

Throughout the report, IRI outlines the key findings from the Barrier Analysis supported by rigorously collected qualitative and quantitative evidence. Recommendations in this report are meant to act as a guide for international implementers to think through how they can better support youth civic engagement in Laos through new and improved programs, policies and practices.

Civic participation is defined by IRI as when citizens act alone or together to protect public values to make a positive change in their community.

Between April 2019 and March 2020, IRI conducted a Barrier Analysis to identify the reasons marginalized youth do or do not adopt a behavior. For the purposes of this analysis, IRI identified youth as individuals between the ages of 18 and 30 years old. The inter-sectionally marginalized communities targeted were the Lesbian, Gay, Bi-Sexual and Transgender (LGBTI) community, religious minorities and women. For each community, seven Doers and seven Non-Doers1 were individually interviewed using a semistructured interview protocol designed by the IRI Laos team and the Evidence and Learning Practice (ELP).

Based on the Institute’s robust experience working with gender focused organizations in Laos, IRI conducted the interviews with young women in Vientiane. Informed by an IRI conducted baseline assessment, IRI determined it would revise the barrier analysis methodology by reducing the number of individuals interviewed. The assessment also confirmed the difficulty in operating in rural areas and conducting interviews with marginalized communities where IRI has limited access. Conducting the barrier analysis with the initial sample number and without the assistance of the selected contractors would have presented logistical challenges in identifying participants and conducting the interviews in a safe and timely manner.

The Behavior Statement: Inter-sectionally marginalized youth in Laos participate in civic engagement activities. Civic engagement is defined as when citizens act alone or together to protect public values and to make a positive change in their community. Activities are defined as any individual or group activity addressing issues of public concern.

42Interviews: Lao youth between the ages 18 – 30

21Doers: Doers are classified as people who participate in

civic engagement activities

21Non-Doers: Non-Doers are classified as people who do not participate in civic engagement activities

14Members of the LGBTI Community: Seven women, including three transgender women

14Religious Minorities:

Three seventh-day adventists, three Lao evangelicals, three catholics, three baha’is and two animists

14Women

In conversations with IRI’s Evaluation and Learning Practice (ELP), it was determined that the adapted methodology would still allow IRI to capture the data needed to inform the analysis in a rigorous manner. As such, IRI selected two credible and qualified individuals to assist in completing the interviews for the LGBTI community and religious minorities: the director of Proud to Be Us Laos (PTBUL), who is a leading voice for LGBTI rights and advocacy, as well as a Project Manager of the Institute for Global Engagement (IGE), who has unprecedented access to Lao religious minority communities, having conducted “peace-building” workshops throughout the country. IRI decided to work with these partners given the sensitivities surrounding these marginalized communities and the importance of pre-established trust for interviewees to be willing to share accurate information with the research team. After data was collected, each contractor met with IRI staff to discuss interviews prior to IRI coding and analyzing the results.

Youth Findings

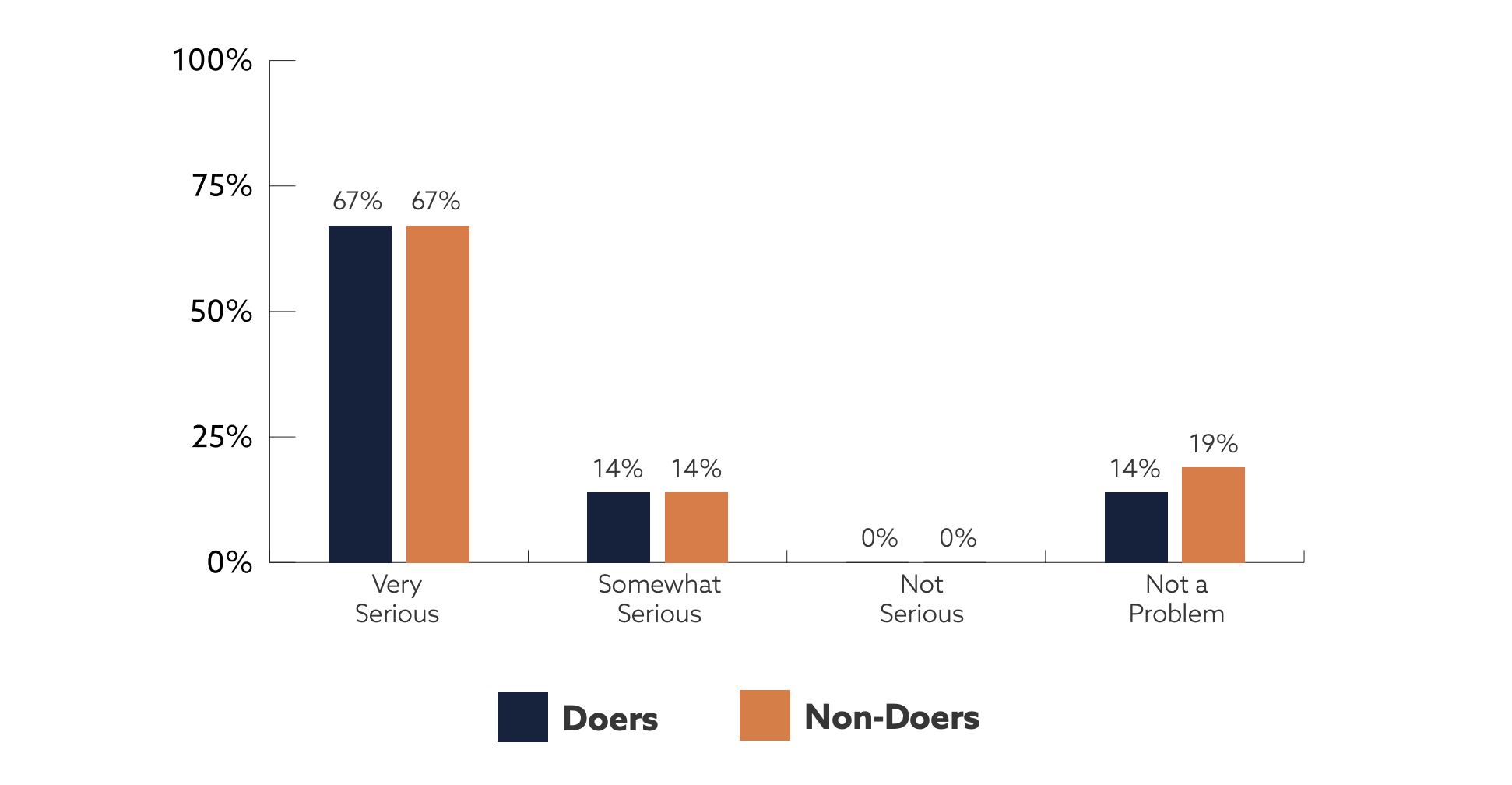

With over 60 percent of the Lao population under the age of 25, it is inevitable that young people will serve a critical role in Laos’ social and economic development.2 IRI’s Barrier Analysis data demonstrated that youth perceive their importance within the development process, with assessment participants expressing that it would be a serious problem if youth were excluded from civic engagement activities. Participants identified the importance of youth voices in the development process to ensure new perspectives are being heard and applied to develop innovative solutions. Participants also noted that it is important that youth are civically engaged so they can understand their rights. According to an LGBTI Doer: “If young people are not aware of civic issues, how can they become a leader when they grow older?”

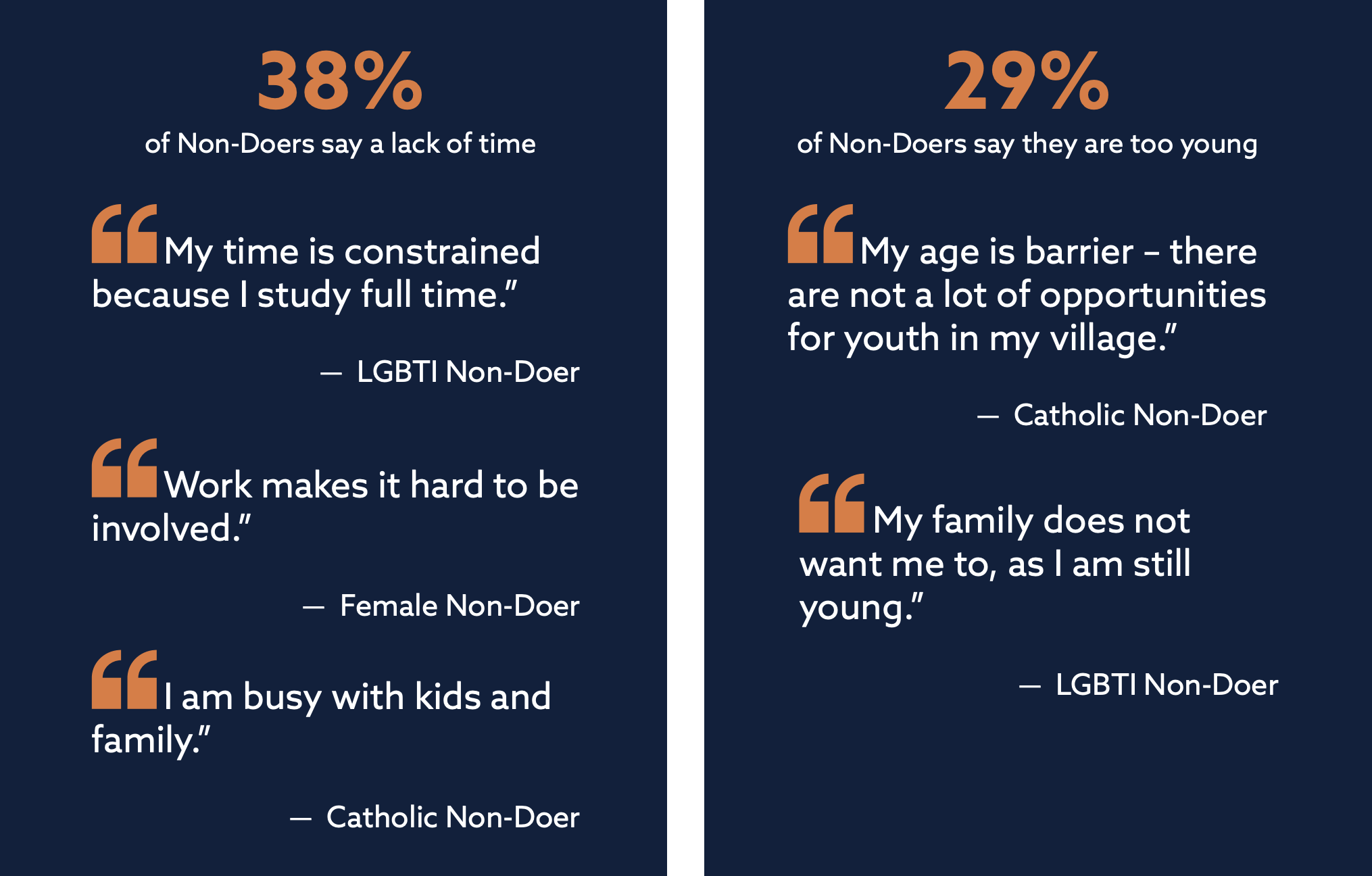

What makes it difficult for you to participate in civic engagement activities?

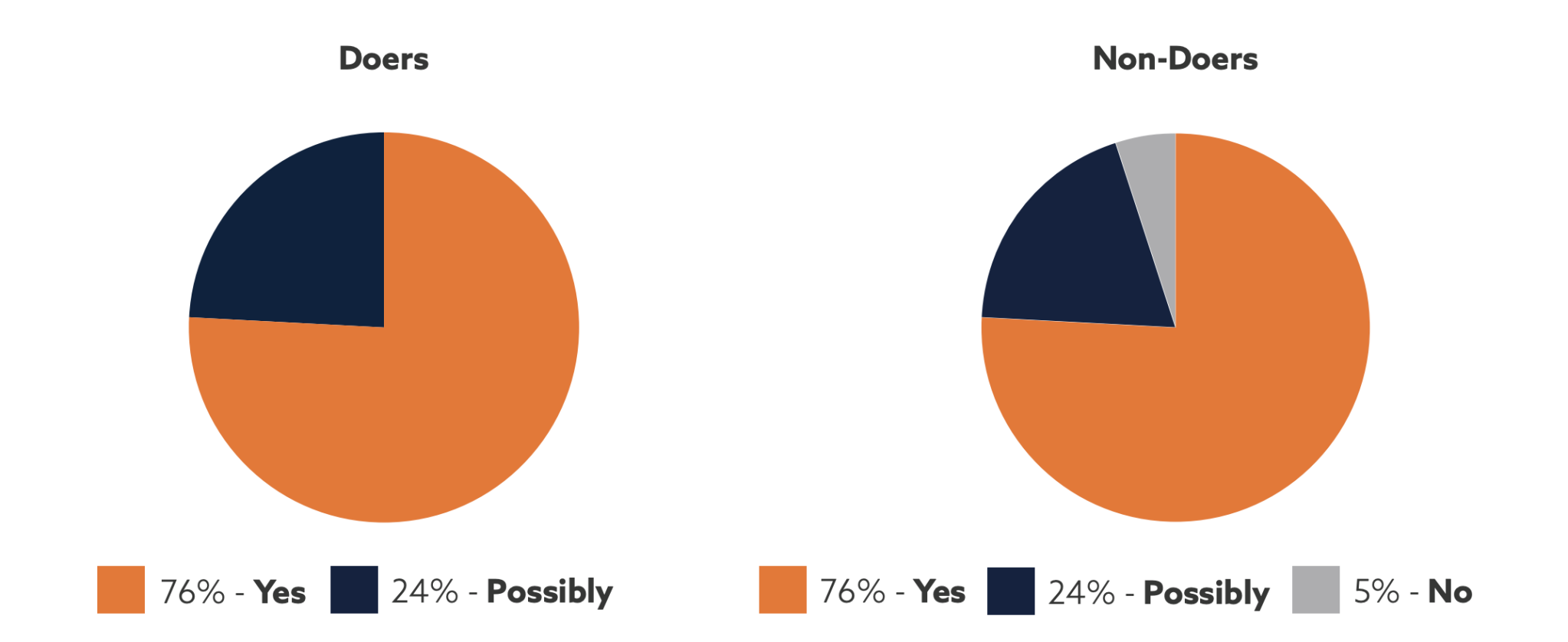

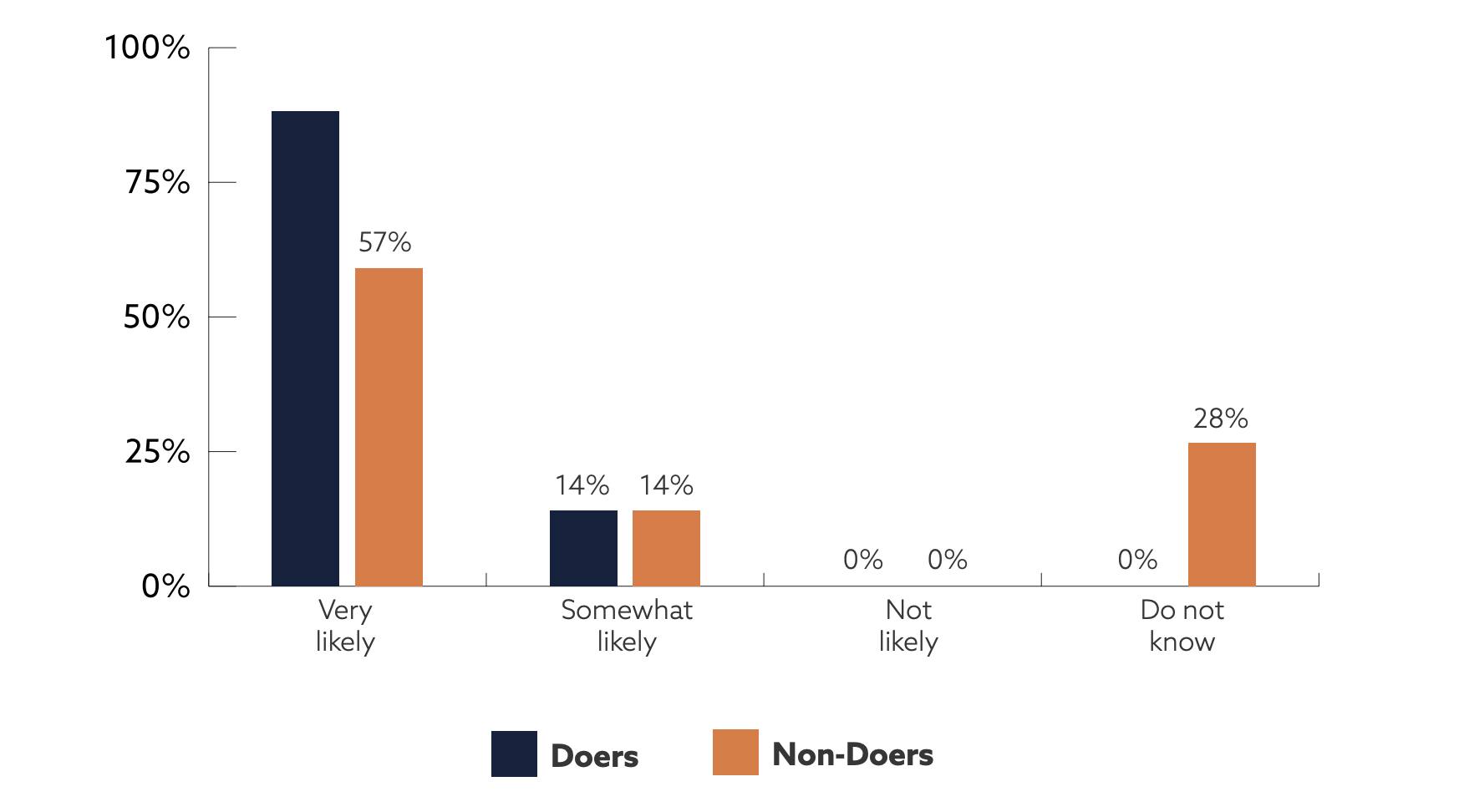

With your present knowledge, resources and skills, do you think you are capable of being involved in civic engagement activities?

With your present knowledge, resources and skills, do you think you are capable of being involved in civic engagement activities?

The Barrier Analysis indicated that Lao youth believe they have the knowledge and skills to be involved in civic engagement activities. In particular, Doers identified leadership and communication skills as enabling factors for their participation. Despite believing in their own capabilities, Non-Doers indicated that there are two main challenges that prevent them from putting their perceived skills into practice:

- They lack the necessary time to commit to civic engagement activities due to work, school and familial obligations; and

- They are too young to be given opportunities to, or effectively participate in, civic engagement activities.

Who, if anyone, does/would not support your decision to participate in civic engagement activities?

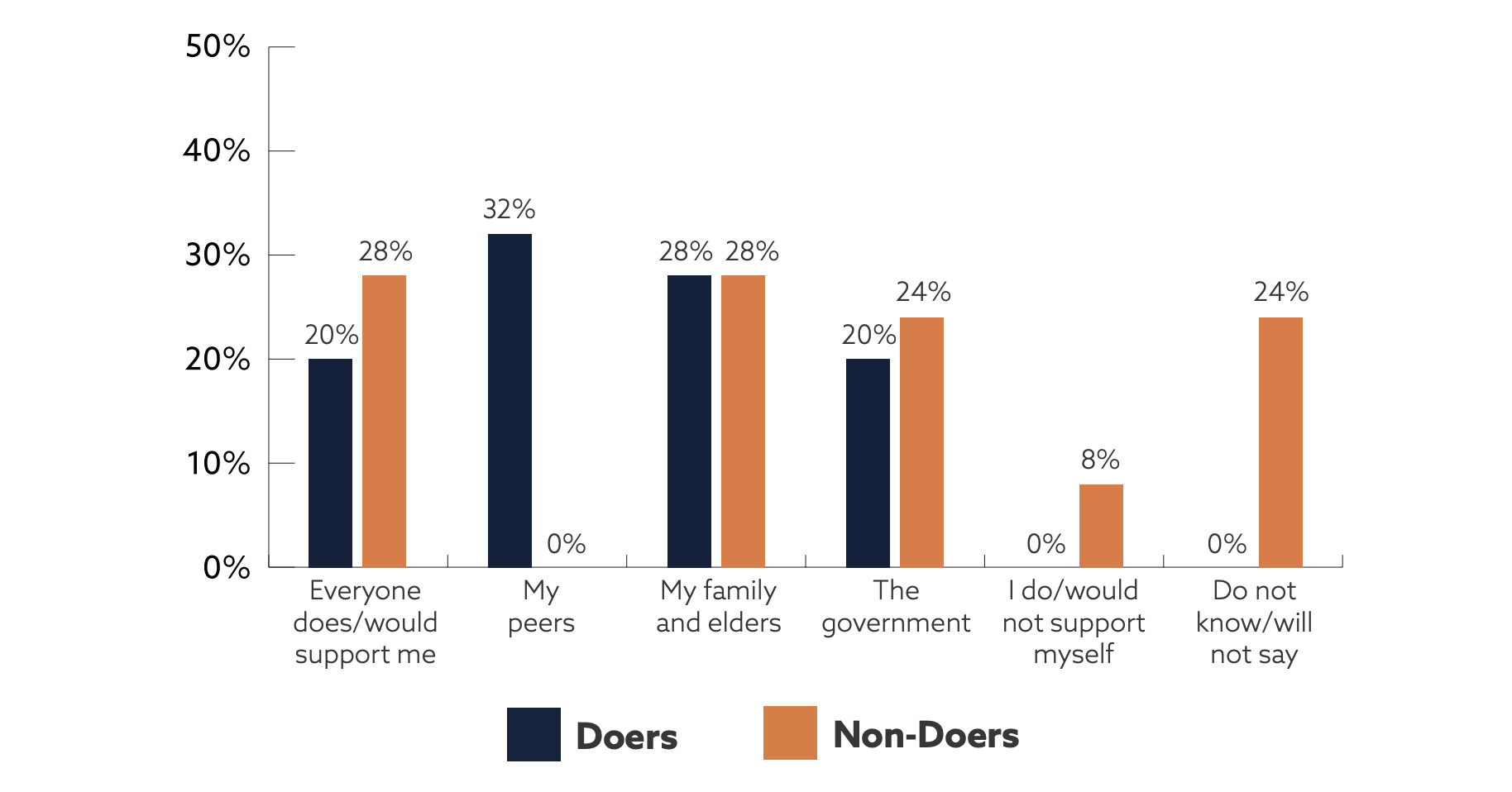

Both Doers and Non-Doers claimed that if their family, government officials and/or peers supported their efforts, they would be more likely to participate in civic engagement activities. In terms of government support, the Government of Laos (GoL) has demonstrated support for the youth population; however, there is no official government framework in place to increase youth civic engagement. For example, the Lao People’s Revolutionary Youth Union (LYU) – the youth wing of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP) – states that their main objective is to organize youth to implement national development goals.3 Regardless of LYU’s stated objective, in actuality, the LYU activities focus on increasing “patriotism and revolutionary values,” rather than promoting youth involvement civic engagement activities.

Recommendation

In Laos, programs should aim to support youth Doers to protect and increase civic space at the local and national level. International implementers should financially and technically support youth Doers to develop and engage in peer education networks that include Non-Doers. Activities should help youth Non-Doers develop a better understanding of the importance of civic engagement, as well as value of young people in Laos’ development process.

LGBTI Findings

The Lao LGBTI community is afforded little domestic legal protections.4 According to Article 35 of the Lao constitution, there are no comprehensive protections against the discrimination of the LGBTI community. In particular, the Constitution only recognizes two genders, leaving intersex individuals with no legal protections.5 In a July 2019 interview with IRI staff, Anan Bouapha, a leader of the LBGT movement in Laos, stated that acceptance is the highest priority for the community. His organization, PTBUL, has focused on educating the general public on LGBTI issues, stressing that there must be social acceptance of the LGBTI community before their organization can advocate for legal protections.6

Stigmatization of the LGBTI community was clearly reflected in the Barrier Analysis findings, with the overwhelming majority of LGBTI respondents associating taboos with their sexuality. Although both Doers and Non-Doers perceive stigmatization, Non-Doers perceived it to be less severe. Based on the Barrier Analysis interview data, IRI estimates that the reasons Non-Doers perceive less taboos related to their sexuality is because they are not involved in activities that publicly support LGBTI rights, therefore, they are less aware of the pervasiveness of LGBTI stigmatization. Anan Bouapha of PTBUL elaborated: “The big difference between Doers and Non-Doers is that Non-Doers do not know what civic engagement is.”

Are there any cultural rules or taboos that are for or against LGBTI peoples participating in civic engagement activities?

For LGBTI Non-Doers, a lack of either national or local level government support was cited as one of the main reasons they are not civically engaged. For example, an LGBTI Non-Doer stated: “I think we are still living in a traditional society with a backward mindset… From my personal view, I might get backlash from the local authority if I participate in civic engagement because there is a cultural issue when it comes to sexual orientation and gender identity.” LGBTI Doers agreed, with one respondent saying that the government is “very traditional and not willing to talk about [LGBTI] issues openly.” Additionally, another Doer stated that the LGBTI community must be “logical in terms of claiming rights protections and understand the cultural politics of Laos by engaging in subtle way.”

In Their Own Words: LGBTI Doers

When it comes to a big gathering or celebration led by a civically engaged member of the LGBTI community, people are likely to think it is a way to convert or persuade young people to become LGBTI.

When it comes to cultural rules, freedom of dressing can be problematic. For instance, a man must dress like a man, and vice versa for women.

Some activities or projects discriminate based on gender identity and expression. There are many youth scholarships that I want to take part in, but I am never selected even though I am qualified.

Being gender queer is not acceptable if you want a leadership position in your career.

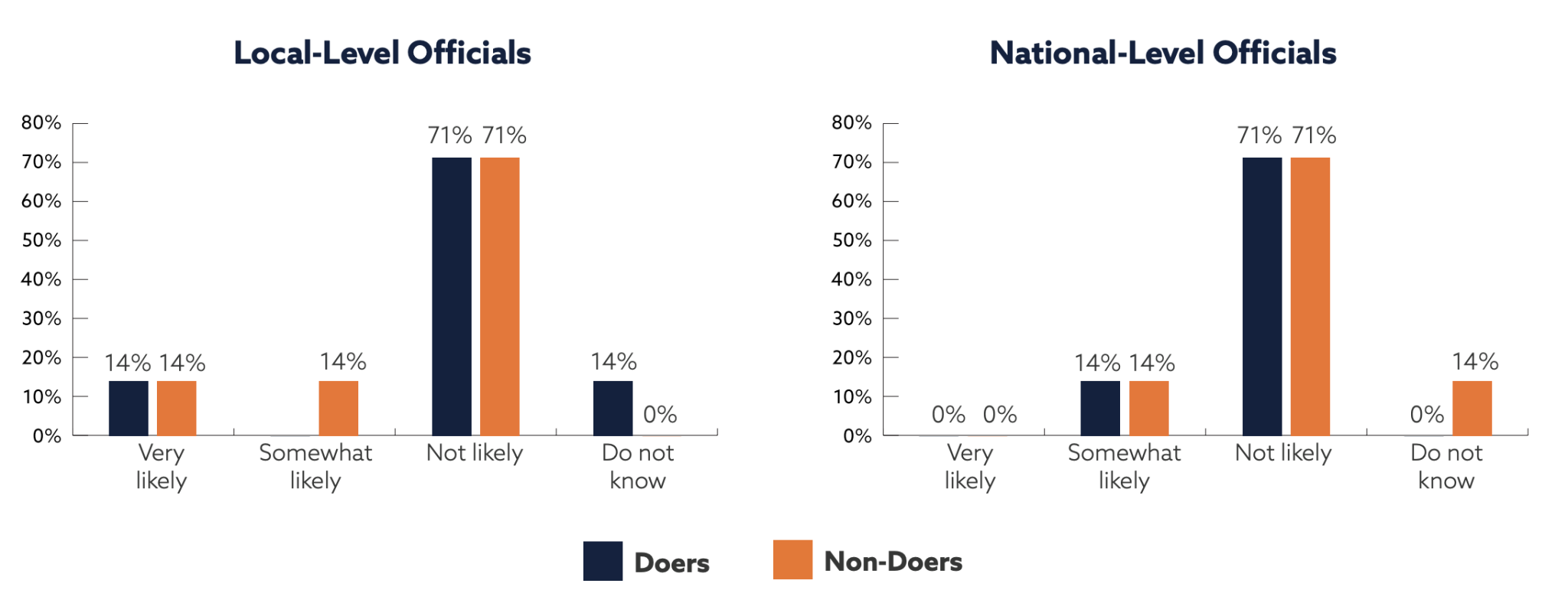

If a large number of LGBTI people participate in civic engagement activities, how likely are government officials to acknowledge and address the needs of the LGBTI community?

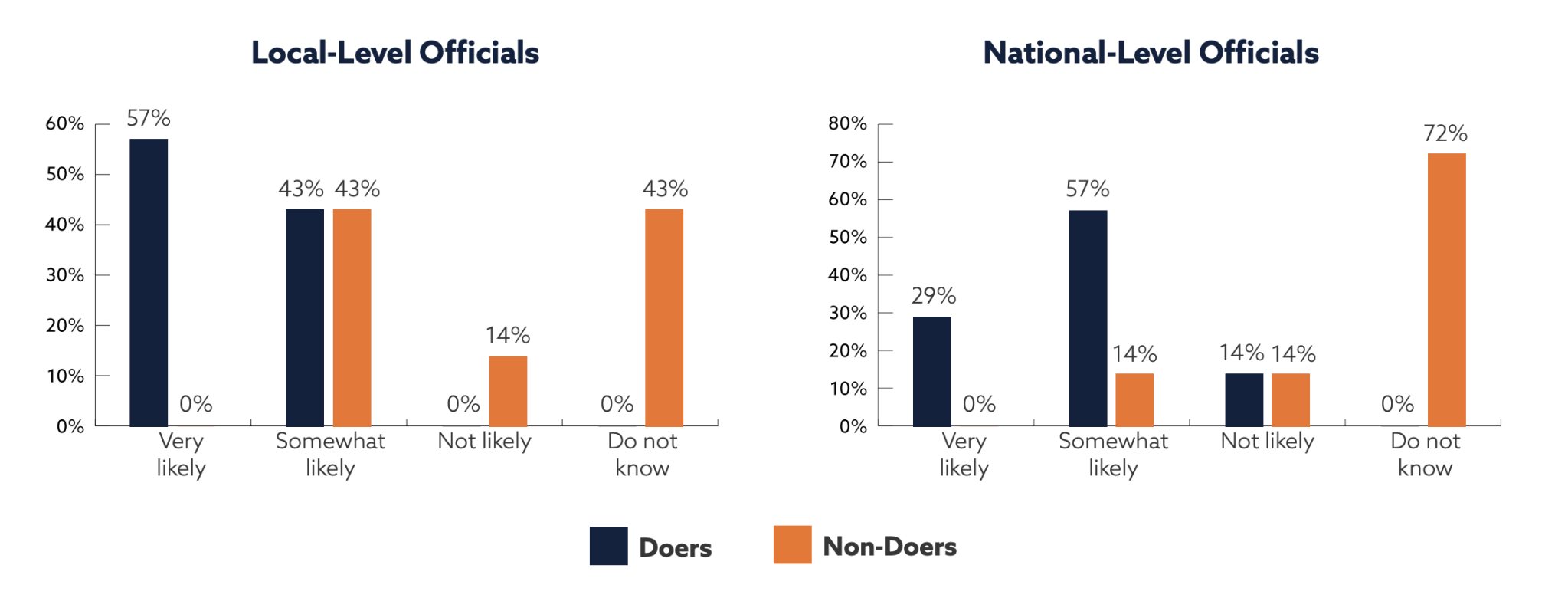

Despite the aforementioned taboos associated with their sexuality, LGBTI Doers overall remain confident that their needs will be represented and listened to by the government officials due to the strong civil society presence representing the LGBTI community. Noteably, in the Lao context, the civil society representatives who act as the voice of the LGBTI community have an acute understanding of ways to access policymakers that allows them to push forward their agenda. In this regard, an LGBTI Doer stated: “Local NPAs like Proud to be Us Laos will be the ones who can make a change. They are able to coordinate with many partners – Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), international groups and the government – to talk about the inclusion of LGBTI people in the community.”

Recommendation

The LGBTI community in Laos has become a growing voice in the human rights sector, advocating for a positive environment in which LGBTI persons can participate in civic engagement activities. Capacity development experts, particularly those with lived experience implementing youth and LGBTI-sensitive programming, should provide support to Lao non-profit associations (NPAs)7 and CSOs to represent LGBTI needs to the government in a context-specific and effective way. Moreover, these youth champions should be given the financial and technical resources to implement programs that reduce societal stigmas surrounding the LGBTI community through public education efforts.

Religious Minority Findings

Lao law provides equal rights for all members of national, racial and ethnic groups. Nonetheless, societal discrimination persists. In some parts of the country, Lao citizens are generally free to practice their chosen religion, especially for the majority Buddhist community. In other areas, local authorities harass and discriminate against religious and ethnic minorities, inconsistently interpreting religious regulations. Decree 315 of the Lao Constitution states: “Lao citizens have the right and freedom to believe or not believe in religions”; however, it also requires religious organizations to register with the government, as well as seek government approval to print religious literature, build religious facilities and travel internationally for religious meetings. Although these measures are not explicitly meant to limit freedom of religion, the Barrier Analysis demonstrated that religious minorities feel a deep sense of marginalization. For example, a Ba’hai Non-Doer stated: “There are many steps of approval process to engage in religious activities [which leads us to have] no control or freedom of religion.”

Barrier Analysis data indicated that a lack of government or institutional support, as well as a fear of legal or societal repercussions, prevents religious minority youth from being civically engaged. In particular, religious minority Doers and Non-Doers feel that if they were to participate in civic engagement activities, local and national-level officials would still be unlikely to acknowledge and address their needs. Moreover, the data clearly pointed toward a feeling that those who are not of the Buddhist faith have less opportunities for civic engagement due to religious stigmatization.

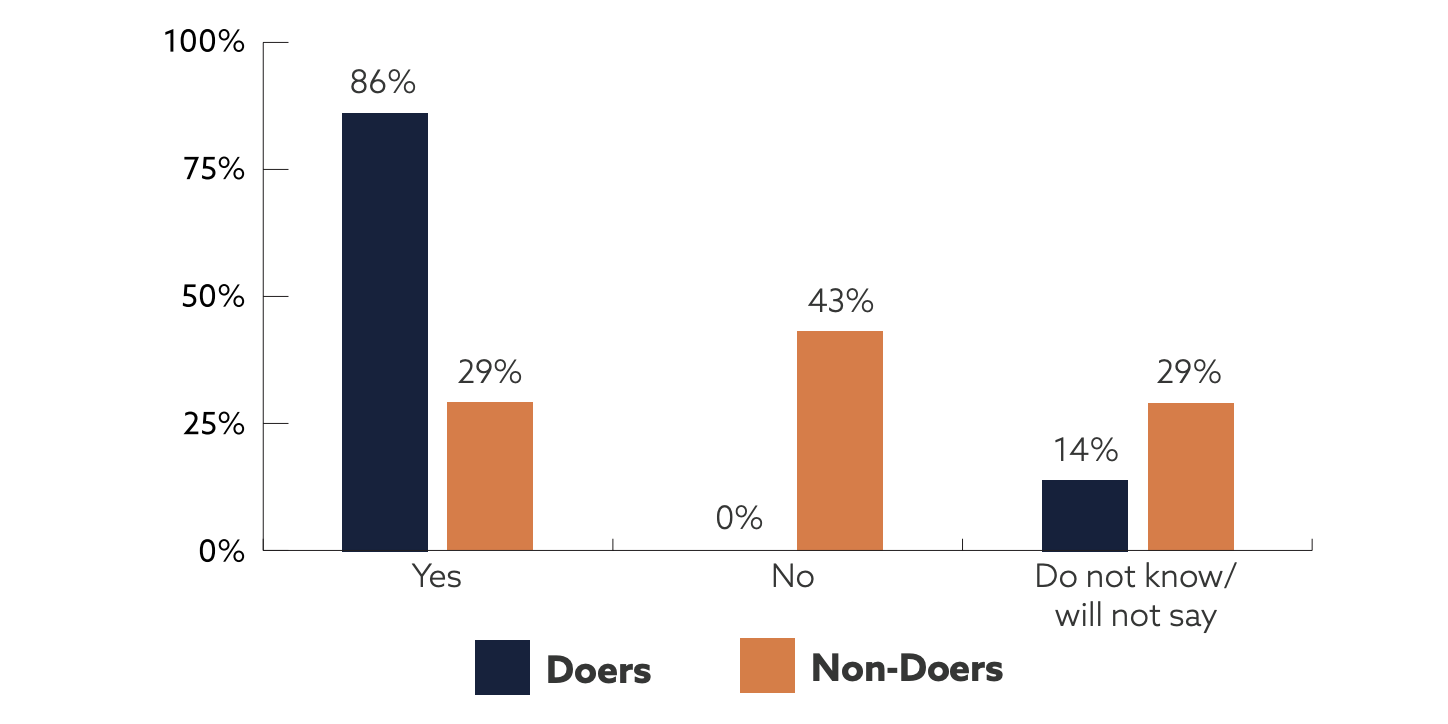

As a religious minority, do you think you would be discouraged from participating in civic engagement activities?

If a large number of people in a religious minority participate in civic engagement activities, how likely are government officials to acknowledge and address the needs of the community?

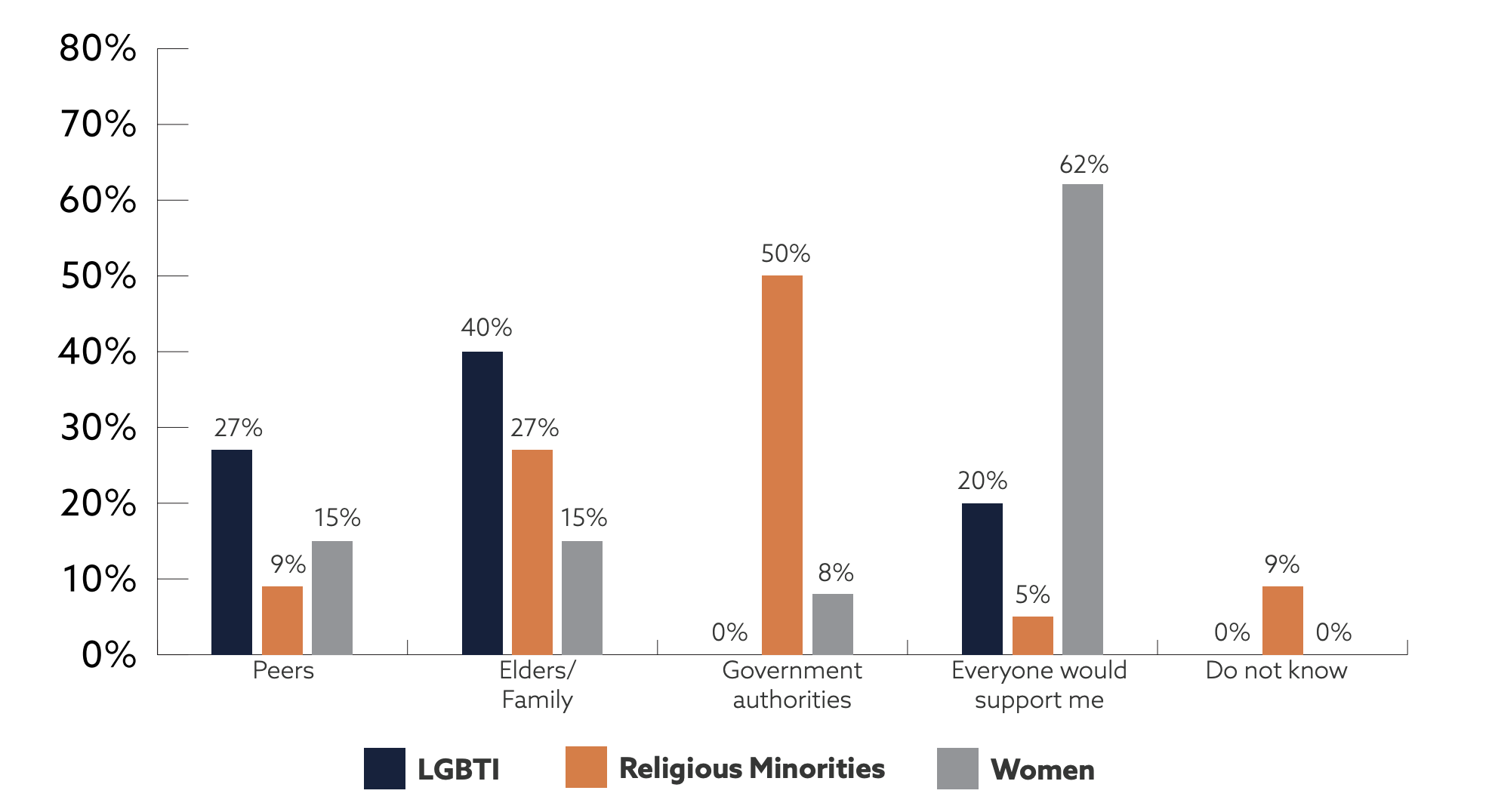

Notably, unlike other marginalized groups featured in the Barrier Analysis, there are no civil society or government institutions that represent religious minorities interests. As seen in the figure below, religious minorities feel that they would specifically not be supported by the government – drastically more so than other groups. In addition, religious minorities were the group with lowest percentage of respondents that feel that everyone would support them if they were to participate in civic engagement activities.

Who, if anyone, would not support that decision to participate in civic engagement activities?

In Their Own Words: Religious Minorities

Because society does not accept my religion, I do not have opportunities like other groups of people.

Seven Day Adventist, Doer

Animism is not considered a religion and people are not interested to learn or to respect our beliefs.

Animist, Non-Doer

I do not have opportunities like people do in other religious groups.

Lao Evangelical Church, Doer

My religion does not have the chances afforded to other groups, I especially do not have the chance to participate in village politics or law making.

Catholic Non-Doer

Religious minorities indicated a deep sense of marginalization – they are not supported or encouraged to participate in civic engagement specifically because of a stigma associated with their religious beliefs. With no civil society organizations or governance institutions representing religious minority interests, religious minority Doers should be encouraged to develop mechanisms – such as NPAs – to help garner government support for issues that matter to their community.

Recommendation

Religious minorities indicated a deep sense of marginalization – they are not supported or encouraged to participate in civic engagement specifically because of a stigma associated with their religious beliefs. With no civil society organizations or governance institutions representing religious minority interests, religious minority Doers should be encouraged to develop mechanisms – such as NPAs – to help garner government support for issues that matter to their community.

Given the sensitivity of discussing issues faced by religious minorities, all support efforts to advocate for the freedom of religion should be framed by promoting a narrative of inclusion through nonsensitive vehicles. For example, one way to ensure religious minority interests are understood by the community and represented to officials is through “soft advocacy” measures. Religious minorities could also engage in advocacy and awareness raising within the existing civil society sector by identifying human rights champions that could raise relevant issues as part of their broader rights awareness work.

“Soft advocacy” uses the term “soft” in a way that mimics the definition of soft power – the ability to shape the preferences of others through appeal and attraction. Soft advocacy is therefore defined as advocacy that uses appeal and attraction to garner support for rights-based interventions. IRI has demonstrated the efficacy of “soft advocacy” in Laos through its September 2019 Digital Story Telling Camp. In order to preserve the camp’s emphasis on advocating for minority populations, IRI emphasized that digital stories should not be negative, but rather demonstrate how diversity makes Laos beautiful and unique. With the government observing this training and providing numerous accolades to IRI in response, the camp demonstrated that IRI’s tactic of “soft advocacy” can be effective and safe.

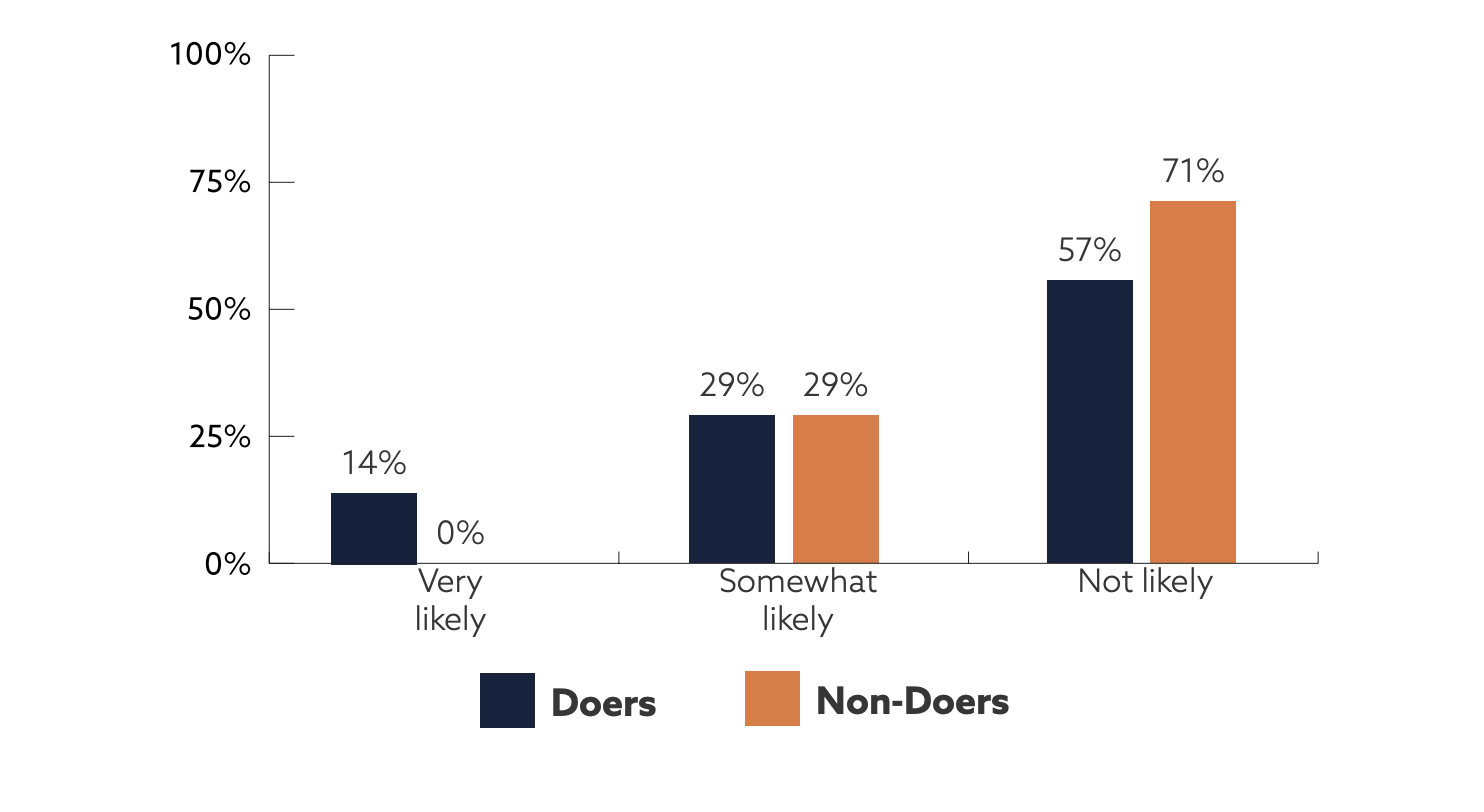

Women Findings

More so than other marginalized communities featured in the Barrier Analysis, women interviewees indicated that they feel represented by their government. Barrier Analysis participants felt that the space for female participation in civic engagement is widening within their communities. This was, for example, indicated by a majority of women answering that they believe they would not be discouraged from participating in civic engagement activities because of their gender. Supporting these claims, a women Doer stated: “I am surprised how open society has become to women participating in any kind of civic engagement activities. A good example is that the current president, or the Speaker of, the National Assembly, is female. There are also a few high-ranking women in the National Assembly and a few female ministers as well.”

The barrier analysis demonstrated that women see their worth in political decision making process.

86%

of Doers and Non-Doers believe it would be a major problem if women were not included in government decision making.

93%

of Doers and Non-Doers believe they have the knowledge and skills to participate in civic engagement activities.

Those who indicated that women are “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to be discouraged from participating in civic engagement activities indicated that this results from a stigmatization surrounding women being divorced or re-married. For example, one respondent noted: “If you are female and you want to be promoted to the head of a department or a government leadership position, if you are not married or you are divorced, it would be difficult for you.” Additionally, some activities are considered to be “for men” only; however, notably those activities are not related to the civic or political sphere, but rather sports and manual labor. Respondents also noted that stigmatization is more prevalent in ethnic and rural communities.

Similar to the LGBTI community, one reason for the increased space for women’s civic engagement is the presence of CSOs that promote gender-equality to the government, such as IRI’s current and previous partners, the Association for the Development of Women’s Legal Education (ADWLE) and the Lao Disabled Women’s Development Center. A women Doer stated that at the national level, “the Lao Women’s Union [which represents female interests in policy making], the Ministry of Peace and the Ministry of Justice have learned about women’s equality through many trainings and consultations with NPAs.” On the sub-national level, a women Non-Doer stated: “Because the local officials attend many trainings with associations on gender-related laws, village authorities are very likely to support women to participate in all activities organized in the community.”

Do you believe that you would be discouraged from participating in civic engagement activities because of your gender?

Despite the positive Barrier Analysis findings, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights reported in his public statement that a woman’s presence in government leadership and policy making is often tokenistic and meant to fill quotas.8 According to a World Bank report, local women are excluded from talks and decision making processes on identifying and managing environmental risks, despite their responsibility in the household for water supply and energy.9 IRI notes that all of the women interviewed in the Barrier Analysis for the gender portion of the assessment were living in Vientiane, which according to IRI’s desk research, likely has more liberal standards for women’s civic engagement.

Recommendation

International development organizations (INGOs) should continue to support NPA engagement with Lao government institutions focused on gender equality, as well as provide technical and financial assistance to NPAs to facilitate trainings on women’s rights. In these interventions, organizations should employ gender-mainstreaming approaches to ensure women are not just “filling quotas.” Moreover, in order to move past the tokenism of women in high-level leadership positions, IRI recommends INGOs support the development of a large cadre of strong and capable Lao women leaders to act as a support network for young women Doers. The cadre’s mentor-level participants should engage young women in leadership trainings and mentorship activities to enhance their confidence and leadership skills. In IRI’s extensive experience engaging young women leaders across Southeast Asia,10 building young women’s self-confidence and skills can be the first step to inspire and equip them to take on greater leadership roles in the government and civil society.

IRI additionally recommends that a Barrier Analysis be conducted in rural Laos to determine barriers to female civic engagement in that context, which is likely significantly more stigmatized based on traditional perceptions of gender norms.

Footnotes

- Doers are classified as people that participate in civic engagement activities. Non-doers do not participate in civic engagement activities.

- Lao Statistics Bureau. “Results of Population and Housing Census 2015 (English Version).” UNFPA Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 12 March, 2017, lao.unfpa. org/en/publications/results-population-and-housing-census-2015-english-version.

- Nielsen, Anne and Vanhmany Chanhsomphou. “Needs and Potential for Rural Youth Development in Lao PDR.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2006, www.fao.org/3/a-ag106e.pdf

- Adam Bemma with Anan Bouapha. “Southeast Dispatches – Episode 10.” (New Natarif, 14 Jan., 2019).

- Bernando de Souza Dantas Fico and Kseniya Kirichenko. UN Human Rights Committee: 123rd Session, (ILGA’s UN Programme, 31 August, 2018).

- Llewellyn, Aisyah. “Southeast Asia Dispatches – Episode 10.” New Naratif , 14 Jan., 2019, newnaratif.com/podcast/southeast-asia-dispatches-episode10/?fbclid=IwAR2p1wMW4zR38_sPcvKU1txMJyhA1ZOxtBKpo_g6Gd8BX8ZQGH4JZs0IKaQ.

- In Laos, NPAs is the official term for civil society organization (CSO).

- Maud de Boer-Buquicchio. “UN Special Rapporteur reports on child protection in Lao PDR.” UN News and Features, (United Nations in Lao PDR, 20 Nov., 2017).

- World Bank Group. “Country Assessment for Lao PDR: Key Findings.” (The World Bank, 1 March, 2013).

- IRI facilitates young women leadership trainings in Burma, Indonesia and in the Pacific Islands, amongst other locations.